Perception is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system, which in turn result from physical or chemical stimulation of the sensory system. Vision involves light striking the retina of the eye; smell is mediated by odor molecules; and hearing involves pressure waves.

In visual perception, an optical illusion is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide variety; their categorization is difficult because the underlying cause is often not clear but a classification proposed by Richard Gregory is useful as an orientation. According to that, there are three main classes: physical, physiological, and cognitive illusions, and in each class there are four kinds: Ambiguities, distortions, paradoxes, and fictions. A classical example for a physical distortion would be the apparent bending of a stick half immerged in water; an example for a physiological paradox is the motion aftereffect. An example for a physiological fiction is an afterimage. Three typical cognitive distortions are the Ponzo, Poggendorff, and Müller-Lyer illusion. Physical illusions are caused by the physical environment, e.g. by the optical properties of water. Physiological illusions arise in the eye or the visual pathway, e.g. from the effects of excessive stimulation of a specific receptor type. Cognitive visual illusions are the result of unconscious inferences and are perhaps those most widely known.

Gestalt psychology, gestaltism, or configurationism is a school of psychology and a theory of perception that emphasises the processing of entire patterns and configurations, and not merely individual components. It emerged in the early twentieth century in Austria and Germany as a rejection of basic principles of Wilhelm Wundt's and Edward Titchener's elementalist and structuralist psychology.

Visual thinking, also called visual or spatial learning or picture thinking, is the phenomenon of thinking through visual processing. Visual thinking has been described as seeing words as a series of pictures. It is common in approximately 60–65% of the general population. "Real picture thinkers", those who use visual thinking almost to the exclusion of other kinds of thinking, make up a smaller percentage of the population. Research by child development theorist Linda Kreger Silverman suggests that less than 30% of the population strongly uses visual/spatial thinking, another 45% uses both visual/spatial thinking and thinking in the form of words, and 25% thinks exclusively in words. According to Kreger Silverman, of the 30% of the general population who use visual/spatial thinking, only a small percentage would use this style over and above all other forms of thinking, and can be said to be true "picture thinkers".

Rudolf Arnheim was a German-born writer, art and film theorist, and perceptual psychologist. He learned Gestalt psychology from studying under Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler at the University of Berlin and applied it to art.

In the philosophy of mind, neuroscience, and cognitive science, a mental image is an experience that, on most occasions, significantly resembles the experience of "perceiving" some object, event, or scene but occurs when the relevant object, event, or scene is not actually present to the senses. There are sometimes episodes, particularly on falling asleep and waking up, when the mental imagery may be dynamic, phantasmagoric, and involuntary in character, repeatedly presenting identifiable objects or actions, spilling over from waking events, or defying perception, presenting a kaleidoscopic field, in which no distinct object can be discerned. Mental imagery can sometimes produce the same effects as would be produced by the behavior or experience imagined.

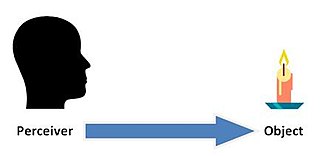

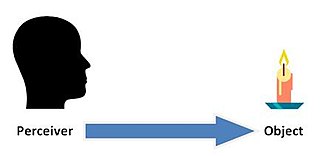

In the philosophy of perception and philosophy of mind, direct or naïve realism, as opposed to indirect or representational realism, are differing models that describe the nature of conscious experiences; out of the metaphysical question of whether the world we see around us is the real world itself or merely an internal perceptual copy of that world generated by our conscious experience.

Visual communication is the use of visual elements to convey ideas and information which include signs, typography, drawing, graphic design, illustration, industrial design, advertising, animation, and electronic resources. Visual communication has been proven to be unique when compared to other verbal or written languages because of its more abstract structure. It stands out for its uniqueness, as the interpretation of signs varies on the viewer's field of experience. The interpretation of imagery is often compared to the set alphabets and words used in oral or written languages. Another point of difference found by scholars is that, though written or verbal languages are taught, sight does not have to be learned and therefore people of sight may lack awareness of visual communication and its influence in their everyday life. Many of the visual elements listed above are forms of visual communication that humans have been using since prehistoric times. Within modern culture, there are several types of characteristics when it comes to visual elements, they consist of objects, models, graphs, diagrams, maps, and photographs. Outside the different types of characteristics and elements, there are seven components of visual communication: color, shape, tones, texture, figure-ground, balance, and hierarchy.

The term composition means "putting together". It can be thought of as the organization of the elements of art according to the principles of art. Composition can apply to any work of art, from music through writing and into photography, that is arranged using conscious thought.

The Ehrenstein illusion is an optical illusion of brightness or colour perception. The visual phenomena was studied by the German psychologist Walter H. Ehrenstein (1899–1961) who originally wanted to modify the theory behind the Hermann grid illusion. In the discovery of the optical illusion, Ehrenstein found that grating patterns of straight lines that stop at a certain point appear to have a brighter centre, compared to the background.

Visual design elements and principles describe fundamental ideas about the practice of visual design.

The psychology of art is the scientific study of cognitive and emotional processes precipitated by the sensory perception of aesthetic artefacts, such as viewing a painting or touching a sculpture. It is an emerging multidisciplinary field of inquiry, closely related to the psychology of aesthetics, including neuroaesthetics.

György Kepes was a Hungarian-born painter, photographer, designer, educator, and art theorist. After immigrating to the U.S. in 1937, he taught design at the New Bauhaus in Chicago. In 1967 he founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) where he taught until his retirement in 1974.

Visual hierarchy, according to Gestalt psychology, is a pattern in the visual field wherein some elements tend to "stand out," or attract attention, more strongly than other elements, suggesting a hierarchy of importance. While it may occur naturally in any visual field, the term is most commonly used in design, where elements are intentionally designed to make some look more important than others. This order is created by the visual contrast between forms in a field of perception. Objects with highest contrast to their surroundings are recognized first by the human mind.

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment through photopic vision, color vision, scotopic vision, and mesopic vision, using light in the visible spectrum reflected by objects in the environment. This is different from visual acuity, which refers to how clearly a person sees. A person can have problems with visual perceptual processing even if they have 20/20 vision.

In neuroscience, functional specialization is a theory which suggests that different areas in the brain are specialized for different functions.

The principles of grouping are a set of principles in psychology, first proposed by Gestalt psychologists to account for the observation that humans naturally perceive objects as organized patterns and objects, a principle known as Prägnanz. Gestalt psychologists argued that these principles exist because the mind has an innate disposition to perceive patterns in the stimulus based on certain rules. These principles are organized into five categories: Proximity, Similarity, Continuity, Closure, and Connectedness.

Form perception is the recognition of visual elements of objects, specifically those to do with shapes, patterns and previously identified important characteristics. An object is perceived by the retina as a two-dimensional image, but the image can vary for the same object in terms of the context with which it is viewed, the apparent size of the object, the angle from which it is viewed, how illuminated it is, as well as where it resides in the field of vision. Despite the fact that each instance of observing an object leads to a unique retinal response pattern, the visual processing in the brain is capable of recognizing these experiences as analogous, allowing invariant object recognition. Visual processing occurs in a hierarchy with the lowest levels recognizing lines and contours, and slightly higher levels performing tasks such as completing boundaries and recognizing contour combinations. The highest levels integrate the perceived information to recognize an entire object. Essentially object recognition is the ability to assign labels to objects in order to categorize and identify them, thus distinguishing one object from another. During visual processing information is not created, but rather reformatted in a way that draws out the most detailed information of the stimulus.

Ideasthesia is a neuropsychological phenomenon in which activations of concepts (inducers) evoke perception-like sensory experiences (concurrents). The name comes from the Ancient Greek ἰδέα and αἴσθησις, meaning 'sensing concepts' or 'sensing ideas'. The notion was introduced by neuroscientist Danko Nikolić as an alternative explanation for a set of phenomena traditionally covered by synesthesia.

Kurt Koffka was a German psychologist and professor. He was born and educated in Berlin, Germany; he died in Northampton, Massachusetts, from coronary thrombosis. He was influenced by his maternal uncle, a biologist, to pursue science. He had many interests including visual perception, brain damage, sound localization, developmental psychology, and experimental psychology. He worked alongside Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler to develop Gestalt psychology. Koffka had several publications including "The Growth of the Mind: An Introduction to Child Psychology" (1924) and "The Principles of Gestalt Psychology" (1935) which elaborated on his research.