The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. The Continental Congress refers to both the First and Second Congresses of 1774–1781 and at the time, also described the Congress of the Confederation of 1781–1789. The Confederation Congress operated as the first federal government until being replaced following ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Until 1785, the Congress met predominantly at what is today Independence Hall in Philadelphia, though it was relocated temporarily on several occasions during the Revolutionary War and the fall of Philadelphia.

Alexander Hamilton was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 during George Washington's presidency.

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836. The bank's formal name, according to section 9 of its charter as passed by Congress, was "The President, Directors, and Company, of the Bank of the United States". While other banks in the US were chartered by and only allowed to have branches in a single state, it was authorized to have branches in multiple states and lend money to the US government.

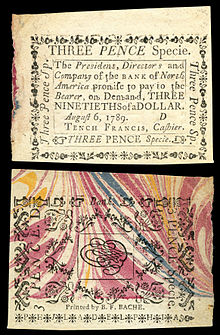

The President, Directors and Company of the Bank of the United States, commonly known as the First Bank of the United States, was a national bank, chartered for a term of twenty years, by the United States Congress on February 25, 1791. It followed the Bank of North America, the nation's first de facto national bank. However, neither served the functions of a modern central bank: They did not set monetary policy, regulate private banks, hold their excess reserves, or act as a lender of last resort. They were national insofar as they were allowed to have branches in multiple states and lend money to the US government. Other banks in the US were each chartered by, and only allowed to have branches in, a single state.

The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 were two United States federal banking acts that established a system of national banks, and created the United States National Banking System. They encouraged development of a national currency backed by bank holdings of U.S. Treasury securities and established the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency as part of the United States Department of the Treasury and a system of nationally chartered banks. The Act shaped today's national banking system and its support of a uniform U.S. banking policy.

The Federal Reserve Act was passed by the 63rd United States Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913. The law created the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States.

In the United States, banking had begun by the 1780s, along with the country's founding. It has developed into a highly influential and complex system of banking and financial services. Anchored by New York City and Wall Street, it is centered on various financial services, such as private banking, asset management, and deposit security.

Robert Morris Jr. was an English-American merchant and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as a member of the Pennsylvania legislature, the Second Continental Congress, and the United States Senate, and he was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the United States Constitution. From 1781 to 1784, he served as the Superintendent of Finance of the United States, becoming known as the "Financier of the Revolution." Along with Alexander Hamilton and Albert Gallatin, he is widely regarded as one of the founders of the financial system of the United States.

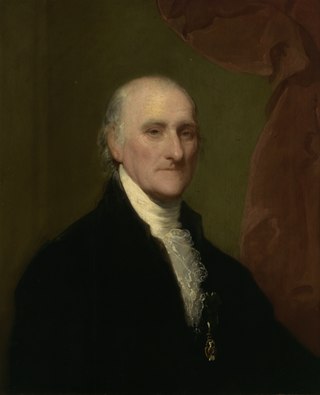

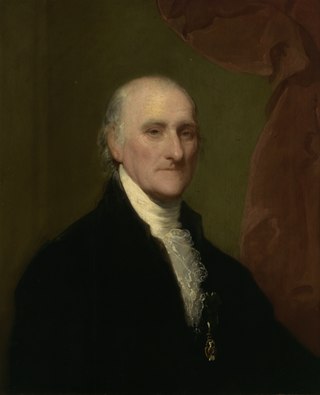

Thomas Willing was an American merchant, politician and slave trader who served as mayor of Philadelphia and was a delegate from Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress. He also served as the first president of the Bank of North America and the First Bank of the United States. During his tenure there he became the richest man in America.

This history of central banking in the United States encompasses various bank regulations, from early wildcat banking practices through the present Federal Reserve System.

CoreStates Financial Corporation, previously known as Philadelphia National Bank (PNB), was an American bank holding company in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, metropolitan area.

Early American currency went through several stages of development during the colonial and post-Revolutionary history of the United States. John Hull was authorized by the Massachusetts legislature to make the earliest coinage of the colony in 1652.

Samuel Miles was an American military officer and politician, as well as an influential businessman and politician, active in Pennsylvania before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War.

John Swanwick was an American merchant, poet and politician. He served in the Pennsylvania General Assembly and from 1795 to 1798 served in the United States representative from Pennsylvania in the 4th and 5th congresses.

The Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 was an anti-government protest by nearly 400 soldiers of the Continental Army in June 1783. The mutiny, and the refusal of the Executive Council of Pennsylvania to stop it, ultimately resulted in Congress of the Confederation vacating Philadelphia and the creation of a federal district, ultimately developed as Washington, D.C., to serve as the national capital.

Superintendent of Finance of the United States was the head of Department of Finance, which is an executive office during the Confederation period with power similar to a finance ministry. The only person to hold the office was Robert Morris, who served from 1781 to 1784, with the assistance of Gouverneur Morris.

The Bank of Pennsylvania or the Pennsylvania Bank can refer to two institutions: one that existed during the American Revolutionary War, and another chartered by the state in 1793.

Monetary policy in the United States is associated with interest rates and availability of credit.

John Barclay was an American soldier, politician, and jurist. He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. He served as President Judge of the Courts for Bucks County, Pennsylvania, alderman in Philadelphia, and Mayor of Philadelphia from 1791 to 1793. He worked as president of the Bank of Pennsylvania and was one of the founders of the Insurance Company of North America. He served as a Federalist member of the Pennsylvania State Senate for the 1st district from 1811 to 1813.

Samuel Howell was an American Quaker who became a prominent merchant in colonial Philadelphia and a leading patriot, proponent, leader and financier for American independence.