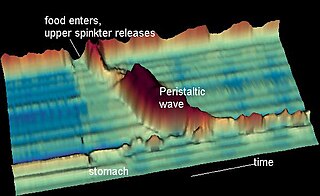

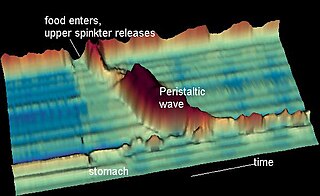

The esophagus or oesophagus, colloquially known also as the food pipe, food tube, or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the stomach. The esophagus is a fibromuscular tube, about 25 cm (10 in) long in adults, that travels behind the trachea and heart, passes through the diaphragm, and empties into the uppermost region of the stomach. During swallowing, the epiglottis tilts backwards to prevent food from going down the larynx and lungs. The word oesophagus is from Ancient Greek οἰσοφάγος (oisophágos), from οἴσω (oísō), future form of φέρω + ἔφαγον.

Esophageal achalasia, often referred to simply as achalasia, is a failure of smooth muscle fibers to relax, which can cause the lower esophageal sphincter to remain closed. Without a modifier, "achalasia" usually refers to achalasia of the esophagus. Achalasia can happen at various points along the gastrointestinal tract; achalasia of the rectum, for instance, may occur in Hirschsprung's disease. The lower esophageal sphincter is a muscle between the esophagus and stomach that opens when food comes in. It closes to avoid stomach acids from coming back up. A fully understood cause to the disease is unknown, as are factors that increase the risk of its appearance. Suggestions of a genetically transmittable form of achalasia exist, but this is neither fully understood, nor agreed upon.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a chronic upper gastrointestinal disease in which stomach content persistently and regularly flows up into the esophagus, resulting in symptoms and/or complications. Symptoms include dental corrosion, dysphagia, heartburn, odynophagia, regurgitation, non-cardiac chest pain, extraesophageal symptoms such as chronic cough, hoarseness, reflux-induced laryngitis, or asthma. In the long term, and when not treated, complications such as esophagitis, esophageal stricture, and Barrett's esophagus may arise.

Esophagitis, also spelled oesophagitis, is a disease characterized by inflammation of the esophagus. The esophagus is a tube composed of a mucosal lining, and longitudinal and circular smooth muscle fibers. It connects the pharynx to the stomach; swallowed food and liquids normally pass through it.

A hiatal hernia or hiatus hernia is a type of hernia in which abdominal organs slip through the diaphragm into the middle compartment of the chest. This may result in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) with symptoms such as a taste of acid in the back of the mouth or heartburn. Other symptoms may include trouble swallowing and chest pains. Complications may include iron deficiency anemia, volvulus, or bowel obstruction.

In medicine or biology, a diverticulum is an outpouching of a hollow structure in the body. Depending upon which layers of the structure are involved, diverticula are described as being either true or false.

Megaesophagus, also known as esophageal dilatation, is a disorder of the esophagus in humans and other mammals, whereby the esophagus becomes abnormally enlarged. Megaesophagus may be caused by any disease which causes the muscles of the esophagus to fail to properly propel food and liquid from the mouth into the stomach. Food can become lodged in the flaccid esophagus, where it may decay, be regurgitated, or maybe inhaled into the lungs.

Abdominal bloating is a short-term disease that affects the gastrointestinal tract. Bloating is generally characterized by an excess buildup of gas, air or fluids in the stomach. A person may have feelings of tightness, pressure or fullness in the stomach; it may or may not be accompanied by a visibly distended abdomen. Bloating can affect anyone of any age range and is usually self-diagnosed, in most cases does not require serious medical attention or treatment. Although this term is usually used interchangeably with abdominal distension, these symptoms probably have different pathophysiological processes, which are not fully understood.

The inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle is a skeletal muscle of the neck. It is the thickest of the three outer pharyngeal muscles. It arises from the sides of the cricoid cartilage and the thyroid cartilage. It is supplied by the vagus nerve. It is active during swallowing, and partially during breathing and speech. It may be affected by Zenker's diverticulum.

Enteric fermentation is a digestive process by which carbohydrates are broken down by microorganisms into simple molecules for absorption into the bloodstream of an animal. Because of human agricultural reliance in many parts of the world on animals which digest by enteric fermentation, it is the second largest anthropogenic factor for the increase in methane emissions directly after fossil fuel use.

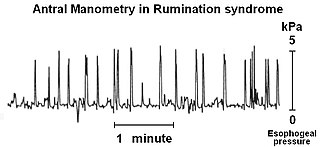

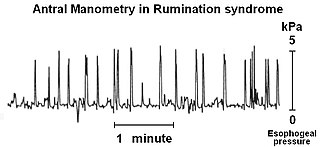

Rumination syndrome, or merycism, is a chronic motility disorder characterized by effortless regurgitation of most meals following consumption, due to the involuntary contraction of the muscles around the abdomen. There is no retching, nausea, heartburn, odour, or abdominal pain associated with the regurgitation as there is with typical vomiting, and the regurgitated food is undigested. The disorder has been historically documented as affecting only infants, young children, and people with cognitive disabilities . It is increasingly being diagnosed in a greater number of otherwise healthy adolescents and adults, though there is a lack of awareness of the condition by doctors, patients, and the general public.

Triple-A syndrome or AAA syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive congenital disorder. In most cases, there is no family history of AAA syndrome. The syndrome was first identified by Jeremy Allgrove and colleagues in 1978; since then just over 100 cases have been reported. The syndrome is called Triple-A due to the manifestation of the illness which includes achalasia, addisonianism, and alacrima. Alacrima is usually the earliest manifestation. Neurodegeneration or atrophy of the nerve cells and autonomic dysfunction may be seen in the disorder; therefore, some have suggested the disorder be called 4A syndrome. It is a progressive disorder that can take years to develop the full-blown clinical picture. The disorder also has variability and heterogeneity in presentation.

Esophageal dysphagia is a form of dysphagia where the underlying cause arises from the body of the esophagus, lower esophageal sphincter, or cardia of the stomach, usually due to mechanical causes or motility problems.

Esophageal spasm is a disorder of motility of the esophagus.

Nutcracker esophagus, jackhammer esophagus, or hypercontractile peristalsis, is a disorder of the movement of the esophagus characterized by contractions in the smooth muscle of the esophagus in a normal sequence but at an excessive amplitude or duration. Nutcracker esophagus is one of several motility disorders of the esophagus, including achalasia and diffuse esophageal spasm. It causes difficulty swallowing, or dysphagia, with both solid and liquid foods, and can cause significant chest pain; it may also be asymptomatic. Nutcracker esophagus can affect people of any age but is more common in the sixth and seventh decades of life.

Cricopharyngeal spasms occur in the cricopharyngeus muscle of the pharynx. Cricopharyngeal spasm is an uncomfortable but harmless and temporary disorder.

Cricopharyngeal myotomy is a surgical sectioning of the cricopharyngeus muscle, also known as the upper esophageal sphincter, that has been advocated for the treatment of cricopharyngeal spasm, or cricopharyngeal achalasia, that leads to cervical dysphagia in the clinical setting.

FutureFeed was established by Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), FutureFeed holds the global intellectual property for the use of Asparagopsis seaweed as a ruminant livestock feed ingredient that can reduce methane emissions by 80% or more. This result can be achieved by the addition of a small amount of the seaweed into the daily diet of livestock. This discovery was made by a team of scientists from CSIRO and James Cook University (JCU), supported by Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA), who came together in 2013 to investigate the methane reduction potential of various native Australian seaweeds.

Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO) is an esophageal motility disorder characterized by increased pressure where the esophagus connects to the stomach at the lower esophageal sphincter. EGJOO is diagnosed by esophageal manometry. However, EGJOO has a variety of etiologies; evaluating the cause of obstruction with additional testing, such as upper endoscopy, computed tomography, or endoscopic ultrasound may be necessary. When possible, treatment of EGJOO should be directed at the cause of obstruction. When no cause for obstruction is found, observation alone may be considered if symptoms are minimal. Functional EGJOO with significant or refractory symptoms may be treated with pneumatic dilation, per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), or botulinum toxin injection.

Retrograde cricopharyngeus dysfunction (R-CPD) is a medical condition first identified by Dr Robert Bastian of the Bastian Voice Institute in which people are unable to burp. Some with the condition are also unable to vomit, or can only do so with great difficulty. It is a lifelong problem that is usually first noted in adolescence, but has also been reported as early as infancy. Most people with this condition also complain of frequent bloating, "gurgling noises" from the throat, frequent flatulence and poor tolerance to carbonated beverages. Many sufferers experience noticeable abdominal distension, with men and women alike saying they look "six months pregnant" by the end of the day. As air is released through the night, the abdomen will assume a more normal appearance by morning.