Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include seizures, hallucinations, trouble speaking, memory problems, and problems with hearing.

Viral meningitis, also known as aseptic meningitis, is a type of meningitis due to a viral infection. It results in inflammation of the meninges. Symptoms commonly include headache, fever, sensitivity to light and neck stiffness.

Myelitis is inflammation of the spinal cord which can disrupt the normal responses from the brain to the rest of the body, and from the rest of the body to the brain. Inflammation in the spinal cord can cause the myelin and axon to be damaged resulting in symptoms such as paralysis and sensory loss. Myelitis is classified to several categories depending on the area or the cause of the lesion; however, any inflammatory attack on the spinal cord is often referred to as transverse myelitis.

Lumbar puncture (LP), also known as a spinal tap, is a medical procedure in which a needle is inserted into the spinal canal, most commonly to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for diagnostic testing. The main reason for a lumbar puncture is to help diagnose diseases of the central nervous system, including the brain and spine. Examples of these conditions include meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. It may also be used therapeutically in some conditions. Increased intracranial pressure is a contraindication, due to risk of brain matter being compressed and pushed toward the spine. Sometimes, lumbar puncture cannot be performed safely. It is regarded as a safe procedure, but post-dural-puncture headache is a common side effect if a small atraumatic needle is not used.

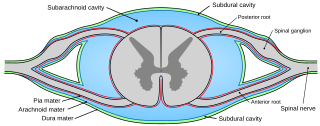

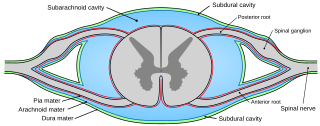

Pia mater, often referred to as simply the pia, is the delicate innermost layer of the meninges, the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Pia mater is medieval Latin meaning "tender mother". The other two meningeal membranes are the dura mater and the arachnoid mater. Both the pia and arachnoid mater are derivatives of the neural crest while the dura is derived from embryonic mesoderm. The pia mater is a thin fibrous tissue that is permeable to water and small solutes. The pia mater allows blood vessels to pass through and nourish the brain. The perivascular space between blood vessels and pia mater is proposed to be part of a pseudolymphatic system for the brain. When the pia mater becomes irritated and inflamed the result is meningitis.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast belonging to the class Tremellomycetes and an obligate aerobe that can live in both plants and animals. Its teleomorph is a filamentous fungus, formerly referred to Filobasidiella neoformans. In its yeast state, it is often found in bird excrement. Cryptococcus neoformans can cause disease in apparently immunocompetent, as well as immunocompromised, hosts.

Cryptococcosis is a potentially fatal fungal infection of mainly the lungs, presenting as a pneumonia, and brain, where it appears as a meningitis. Cough, difficulty breathing, chest pain and fever are seen when the lungs are infected. When the brain is infected, symptoms include headache, fever, neck pain, nausea and vomiting, light sensitivity and confusion or changes in behavior. It can also affect other parts of the body including skin, where it may appear as several fluid-filled nodules with dead tissue.

Arachnoiditis is an inflammatory condition of the arachnoid mater or 'arachnoid', one of the membranes known as meninges that surround and protect the central nervous system. The outermost layer of the meninges is the dura mater and adheres to inner surface of the skull and vertebrae. The arachnoid is under or "deep" to the dura and is a thin membrane that adheres directly to the surface of the brain and spinal cord.

Aseptic meningitis is the inflammation of the meninges, a membrane covering the brain and spinal cord, in patients whose cerebral spinal fluid test result is negative with routine bacterial cultures. Aseptic meningitis is caused by viruses, mycobacteria, spirochetes, fungi, medications, and cancer malignancies. The testing for both meningitis and aseptic meningitis is mostly the same. A cerebrospinal fluid sample is taken by lumbar puncture and is tested for leukocyte levels to determine if there is an infection and goes on to further testing to see what the actual cause is. The symptoms are the same for both meningitis and aseptic meningitis but the severity of the symptoms and the treatment can depend on the certain cause.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a condition seen in some cases of HIV/AIDS or immunosuppression, in which the immune system begins to recover, but then responds to a previously acquired opportunistic infection with an overwhelming inflammatory response that paradoxically makes the symptoms of infection worse.

Neurosyphilis is the infection of the central nervous system in a patient with syphilis. In the era of modern antibiotics, the majority of neurosyphilis cases have been reported in HIV-infected patients. Meningitis is the most common neurological presentation in early syphilis. Tertiary syphilis symptoms are exclusively neurosyphilis, though neurosyphilis may occur at any stage of infection.

Myelography is a type of radiographic examination that uses a contrast medium to detect pathology of the spinal cord, including the location of a spinal cord injury, cysts, and tumors. Historically the procedure involved the injection of a radiocontrast agent into the cervical or lumbar spine, followed by several X-ray projections. Today, myelography has largely been replaced by the use of MRI scans, although the technique is still sometimes used under certain circumstances – though now usually in conjunction with CT rather than X-ray projections.

Tuberculous meningitis, also known as TB meningitis or tubercular meningitis, is a specific type of bacterial meningitis caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of the meninges—the system of membranes which envelop the central nervous system.

Leptomeningeal cancer is a rare complication of cancer in which the disease spreads from the original tumor site to the meninges surrounding the brain and spinal cord. This leads to an inflammatory response, hence the alternative names neoplastic meningitis (NM), malignant meningitis, or carcinomatous meningitis. The term leptomeningeal describes the thin meninges, the arachnoid and the pia mater, between which the cerebrospinal fluid is located. The disorder was originally reported by Eberth in 1870. It is also known as leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, leptomeningeal disease (LMD), leptomeningeal metastasis, meningeal metastasis and meningeal carcinomatosis.

Mollaret's meningitis is a recurrent or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, known collectively as the meninges. Since Mollaret's meningitis is a recurrent, benign (non-cancerous), aseptic meningitis, it is also referred to as benign recurrent lymphocytic meningitis. It was named for Pierre Mollaret, the French neurologist who first described it in 1944.

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, intense headache, vomiting and neck stiffness and occasionally photophobia.

A cerebrospinal fluid leak is a medical condition where the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that surrounds the brain and spinal cord leaks out of one or more holes or tears in the dura mater. A CSF leak is classed as either nonspontaneous (primary), having a known cause, or spontaneous (secondary) where the cause is not readily evident. Causes of a primary CSF leak are those of trauma including from an accident or intentional injury, or arising from a medical intervention known as iatrogenic. A basilar skull fracture as a cause can give the sign of CSF leakage from the ear nose or mouth. A lumbar puncture can give the symptom of a post-dural-puncture headache.

Drug-Induced Aseptic Meningitis (DIAM) is a type of aseptic meningitis related to the use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or biologic drugs such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Additionally, this condition generally shows clinical improvement after cessation of the medication, as well as a tendency to relapse with resumption of the medication.

Tarlov cysts, are type II innervated meningeal cysts, cerebrospinal-fluid-filled (CSF) sacs most frequently located in the spinal canal of the sacral region of the spinal cord (S1–S5) and much less often in the cervical, thoracic or lumbar spine. They can be distinguished from other meningeal cysts by their nerve-fiber-filled walls. Tarlov cysts are defined as cysts formed within the nerve-root sheath at the dorsal root ganglion. The etiology of these cysts is not well understood; some current theories explaining this phenomenon have not yet been tested or challenged but include increased pressure in CSF, filling of congenital cysts with one-way valves, inflammation in response to trauma and disease. They are named for American neurosurgeon Isadore Tarlov, who described them in 1938.

Lymphocytic pleocytosis is an abnormal increase in the amount of lymphocytes in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). It is usually considered to be a sign of infection or inflammation within the nervous system, and is encountered in a number of neurological diseases, such as pseudomigraine, Susac's syndrome, and encephalitis. While lymphocytes make up roughly a quarter of all white blood cells (WBC) in the body, they are generally rare in the CSF. Under normal conditions, there are usually less than 5 white blood cells per µL of CSF. In a pleocytic setting, the number of lymphocytes can jump to more than 1,000 cells per µL. Increases in lymphocyte count are often accompanied by an increase in cerebrospinal protein concentrations in addition to pleocytosis of other types of white blood cells.