Related Research Articles

Asperger syndrome (AS), also known as Asperger's syndrome, formerly described a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction and nonverbal communication, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. The syndrome has been merged with other disorders into autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is no longer considered a stand-alone diagnosis. It was considered milder than other diagnoses that were merged into ASD due to relatively unimpaired spoken language and intelligence.

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a genetic disorder characterized by mild-to-moderate intellectual disability. The average IQ in males with FXS is under 55, while about two thirds of affected females are intellectually disabled. Physical features may include a long and narrow face, large ears, flexible fingers, and large testicles. About a third of those affected have features of autism such as problems with social interactions and delayed speech. Hyperactivity is common, and seizures occur in about 10%. Males are usually more affected than females.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by executive dysfunction occasioning symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity and emotional dysregulation that are excessive and pervasive, impairing in multiple contexts, and otherwise age-inappropriate.

The diagnostic category pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), as opposed to specific developmental disorders (SDD), was a group of disorders characterized by delays in the development of multiple basic functions including socialization and communication. It was defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

Childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD), also known as Heller's syndrome and disintegrative psychosis, is a rare condition characterized by late onset of developmental delays—or severe and sudden reversals—in language, social engagement, bowel and bladder, play and motor skills. Researchers have not been successful in finding a cause for the disorder. CDD has some similarities to autism and is sometimes considered a low-functioning form of it. In May 2013, CDD, along with other sub-types of PDD, was fused into a single diagnostic term called "autism spectrum disorder" under the new DSM-5 manual.

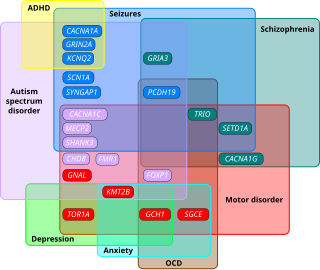

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are neurodevelopmental disorders that begin in early childhood, persist throughout adulthood, and affect three crucial areas of development: communication, social interaction and restricted patterns of behavior. There are many conditions comorbid to autism spectrum disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy.

Hyperfocus is an intense form of mental concentration or visualization that focuses consciousness on a subject, topic, or task. In some individuals, various subjects or topics may also include daydreams, concepts, fiction, the imagination, and other objects of the mind. Hyperfocus on a certain subject can cause side-tracking away from assigned or important tasks.

Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is the persistence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. It is a neurodevelopmental disorder, meaning symptoms must have been present in childhood except for when ADHD occurs after a traumatic brain injury. Specifically, multiple symptoms must be present before the age of 12, according to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. The cutoff age of 12 is a change from the previous requirement of symptom onset, which was before the age of 7 in the DSM-IV. This was done to add flexibility in the diagnosis of adults. ADHD was previously thought to be a childhood disorder that improved with age, but recent research has disproved this. Approximately two-thirds of childhood cases of ADHD continue into adulthood, with varying degrees of symptom severity that change over time, and continue to affect individuals with symptoms ranging from minor inconveniences to impairments in daily functioning.

High-functioning autism (HFA) was historically an autism classification where a person exhibits no intellectual disability, but may experience difficulty in communication, emotion recognition, expression, and social interaction.

Nonverbal learning disability (NVLD) is a proposed category of neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by core deficits in visual-spatial processing and a significant discrepancy between verbal and nonverbal intelligence. A review of papers found that proposed diagnostic criteria were inconsistent. Proposed additional diagnostic criteria include intact verbal intelligence, and deficits in the following: visuoconstruction abilities, speech prosody, fine motor coordination, mathematical reasoning, visuospatial memory and social skills. NVLD is not recognised by the DSM-5 and is not clinically distinct from learning disorder.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to autism:

Autism therapies include a wide variety of therapies that help people with autism, or their families. Such methods of therapy seek to aid autistic people in dealing with difficulties and increase their functional independence.

Despite the scientifically well-established nature of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), its diagnosis, and its treatment, each of these has been controversial since the 1970s. The controversies involve clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents, and the media. Positions range from the view that ADHD is within the normal range of behavior to the hypothesis that ADHD is a genetic condition. Other areas of controversy include the use of stimulant medications in children, the method of diagnosis, and the possibility of overdiagnosis. In 2009, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, while acknowledging the controversy, stated that the current treatments and methods of diagnosis are based on the dominant view of the academic literature.

Alternative therapies for developmental and learning disabilities include a range of practices used in the treatment of dyslexia, ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, Down syndrome and other developmental and learning disabilities. Treatments include changes in diet, dietary supplements, biofeedback, chelation therapy, homeopathy, massage and yoga. These therapies generally rely on theories that have little scientific basis, lacking well-controlled, large, randomized trials to demonstrate safety and efficacy; small trials that have reported beneficial effects can be generally explained by the ordinary waxing and waning of the underlying conditions.

In psychology and neuroscience, executive dysfunction, or executive function deficit, is a disruption to the efficacy of the executive functions, which is a group of cognitive processes that regulate, control, and manage other cognitive processes. Executive dysfunction can refer to both neurocognitive deficits and behavioural symptoms. It is implicated in numerous psychopathologies and mental disorders, as well as short-term and long-term changes in non-clinical executive control. Executive dysfunction is the mechanism underlying ADHD Paralysis, and in a broader context, it can encompass other cognitive difficulties like planning, organizing, initiating tasks and regulating emotions. It is a core characteristic of ADHD and can elucidate numerous other recognized symptoms.

Classic autism, also known as childhood autism, autistic disorder, (early) infantile autism, infantile psychosis, Kanner's autism,Kanner's syndrome, or (formerly) just autism, is a neurodevelopmental condition first described by Leo Kanner in 1943. It is characterized by atypical and impaired development in social interaction and communication as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors, activities, and interests. These symptoms first appear in early childhood and persist throughout life.

Mental disorders diagnosed in childhood can be neurodevelopmental, emotional, or behavioral disorders. These disorders negatively impact the mental and social wellbeing of a child, and children with these disorders require support from their families and schools. Childhood mental disorders often persist into adulthood. These disorders are usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence, as laid out in the DSM-5 and in the ICD-11.

Autism, formally called autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autism spectrum condition (ASC), is a neurodevelopmental disorder marked by deficits in reciprocal social communication and the presence of restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior. Other common signs include difficulties with social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, along with perseverative interests, stereotypic body movements, rigid routines, and hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input. Autism is clinically regarded as a spectrum disorder, meaning that it can manifest very differently in each person. For example, some are nonspeaking, while others have proficient spoken language. Because of this, there is wide variation in the support needs of people across the autism spectrum.

Autism is characterized by the early onset of impairments in reciprocal social interaction and communication and restricted repetitive behaviors or interests. One of the many hypotheses explaining the psychopathology of autism, the deficit in joint attention hypothesis is prominent in explaining the disorder's social and communicative deficits. Nonverbal autism is a subset of autism spectrum where the person does not learn how to speak. One study has shown that 64% of autistic children who are nonverbal at age 5, are still nonverbal 10 years later.

Social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SPCD), also known as pragmatic language impairment (PLI), is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significant difficulties in the social use of verbal and nonverbal communication. Individuals with SPCD struggle to effectively engage in social interactions, interpret social cues, and use language appropriately in social contexts. This disorder can have a profound impact on an individual's ability to establish and maintain relationships, navigate social situations, and participate in academic and professional settings. Although SPCD shares similarities with other communication disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), it is recognized as a distinct diagnostic category with its own set of diagnostic criteria and features.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Michael Rutter; Dorothy V. M. Bishop; Daniel S. Pine; et al., eds. (2008). Rutter's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Dorothy Bishop and Michael Rutter (5th ed.). Blackwell Publishing. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-1-4051-4549-7.

- ↑ "ICD 10". priory.com.

- ↑ National, Disabilities Learning (1982). "Learning disabilities: Issues on definition". Asha. 24 (11): 945–947.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Communication Disorders. (n.d.). Children's Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, WI, Retrieved December 6, 2011, from http://www.chw.org/display/PPF/DocID/

- 1 2 Karmiloff Annette (October 1998). "Development itself is key to understanding developmental disorders". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2 (10): 389–398. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(98)01230-3. PMID 21227254. S2CID 38117177.

- 1 2 Perry, Bruce D. and Szalavitz, Maia. "The Boy Who Was Raised As A Dog", Basic Books, 2006, p.2. ISBN 978-0-465-05653-8

- ↑ Payne, Kim John. “Simplicity Parenting: Using the Extraordinary Power of Less to Raise Calmer, Happier, and More Secure Kids”, Ballantine Books, 2010, p. 9. ISBN 9780345507983

- ↑ "Deciphering Developmental Disorders (DDD) project". www.ddduk.org. Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ↑ McRae, Jeremy F.; Clayton, Stephen; Fitzgerald, Tomas W.; Kaplanis, Joanna; Prigmore, Elena; Rajan, Diana; Sifrim, Alejandro; Aitken, Stuart; Akawi, Nadia (2017). "Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders" (PDF). Nature. 542 (7642): 433–438. Bibcode:2017Natur.542..433M. doi:10.1038/nature21062. PMC 6016744 . PMID 28135719.

- ↑ Walsh, Fergus (2017-01-25). "Child gene study identifies new developmental disorders". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ↑ "Hunting for Autism's Earliest Clues". Autism Speaks. 18 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 Dereu, Mieke. (2010). Screening for Autism Spectrum Disorders in Flemish Day-Care Centers with the Checklist for Early Signs of Developmental Disorders. Springer Science+Business Media. 1247-1258.

- 1 2 "Autism Spectrum Disorders - Pediatrics". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ↑ "Autism: Facts, causes, risk-factors, symptoms, & management". FactDr. 2018-06-25. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ↑ Lau, Yolanda C.; Hinkley, Leighton B. N.; Bukshpun, Polina; Strominger, Zoe A.; Wakahiro, Mari L. J.; Baron-Cohen, Simon; Allison, Carrie; Auyeung, Bonnie; Jeremy, Rita J.; Nagarajan, Srikantan S.; Sherr, Elliott H. (May 2013). "Autism traits in individuals with agenesis of the corpus callosum". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 43 (5): 1106–1118. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1653-2. ISSN 0162-3257. PMC 3625480 . PMID 23054201.

- ↑ Gotts S. J.; Simmons W. K.; Milbury L. A.; Wallace G. L.; Cox R. W.; Martin A. (2012). "Fractionation of social brain circuits in autism spectrum disorders". Brain. 135 (9): 2711–2725. doi:10.1093/brain/aws160. PMC 3437021 . PMID 22791801.

- ↑ Subbaraju V, Sundaram S, Narasimhan S (2017). "Identification of lateralized compensatory neural activities within the social brain due to autism spectrum disorder in adolescent males". European Journal of Neuroscience. 47 (6): 631–642. doi:10.1111/ejn.13634. PMID 28661076. S2CID 4306986.

- ↑ Myers, Scott M.; Johnson, Chris Plauché (1 November 2007). "Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders". Pediatrics. 120 (5): 1162–1182. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2362 . ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 17967921.

- ↑ "Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA): What is ABA?". Autism partnership. 16 June 2011.

- ↑ Matson, Johnny; Hattier, Megan; Belva, Brian (January–March 2012). "Treating adaptive living skills of persons with autism using applied behavior analysis: A review". Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 6 (1): 271–276. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.05.008.

- ↑ Summers, Jane; Sharami, Ali; Cali, Stefanie; D'Mello, Chantelle; Kako, Milena; Palikucin-Reljin, Andjelka; Savage, Melissa; Shaw, Olivia; Lunsky, Yona (November 2017). "Self-Injury in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability: Exploring the Role of Reactivity to Pain and Sensory Input". Brain Sci. 7 (11): 140. doi: 10.3390/brainsci7110140 . PMC 5704147 . PMID 29072583.

- ↑ "Applied Behavioral Strategies - Getting to Know ABA". Archived from the original on 2015-10-07. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ Crabtree, Lisa (2018). "Occupational Therapy's Role with Autism". American Occupational Therapy Association.

- 1 2 3 "What Treatments are Available for Speech, Language and Motor Issues?". Autism Speaks. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ↑ "Speech and Language Therapy". Autism Education Trust. Archived from the original on 2018-03-25.

- ↑ Smith, M; Segal, J; Hutman, T. "Autism Spectrum Disorders". HelpGuide.

- 1 2 Tresco, Katy E. (2004). Attention Deficit Disorders: School-Based Interventions. Pennsylvania: Bethlehem.

- 1 2 "Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADD, ADHD) - Pediatrics". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ↑ Tripp G, Wickens JR. Neurobiology of ADHD. Neuropharmacology. 2009 Dec;57(7-8):579-89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.07.026. Epub 2009 Jul 21. PMID: 19627998.

- ↑ Austerman J. ADHD and behavioral disorders: Assessment, management, and an update from DSM-5. Cleve Clin J Med. 2015 Nov;82(11 Suppl 1):S2-7. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.82.s1.01. PMID: 26555810.

- ↑ C. W. Popper (1997). "Antidepressants in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry . 58 (Suppl 14): 14–29. PMID 9418743.