Related Research Articles

National Wildlife RefugeSystem (NWRS) is a system of protected areas of the United States managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an agency within the Department of the Interior. The National Wildlife Refuge System is the system of public lands and waters set aside to conserve America's fish, wildlife, and plants. Since President Theodore Roosevelt designated Florida's Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge as the first wildlife refuge in 1903, the system has grown to over 568 national wildlife refuges and 38 wetland management districts encompassing about 856,000,000 acres (3,464,109 km2).

The Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 is an Act of Congress passed in 1972 to encourage coastal states to develop and implement coastal zone management plans (CZMPs). This act was established as a United States National policy to preserve, protect, develop, and where possible, restore or enhance, the resources of the Nation's coastal zone for this and succeeding generations.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is the primary law in the United States for protecting and conserving imperiled species. Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation", the ESA was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973. The Supreme Court of the United States described it as "the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species enacted by any nation". The purposes of the ESA are two-fold: to prevent extinction and to recover species to the point where the law's protections are not needed. It therefore "protect[s] species and the ecosystems upon which they depend" through different mechanisms. For example, section 4 requires the agencies overseeing the Act to designate imperiled species as threatened or endangered. Section 9 prohibits unlawful ‘take,’ of such species, which means to "harass, harm, hunt..." Section 7 directs federal agencies to use their authorities to help conserve listed species. The Act also serves as the enacting legislation to carry out the provisions outlined in The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The Supreme Court found that "the plain intent of Congress in enacting" the ESA "was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost." The Act is administered by two federal agencies, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). FWS and NMFS have been delegated by the Act with the authority to promulgate any rules and guidelines within the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) to implement its provisions.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) was the first act of the United States Congress to call specifically for an ecosystem approach to wildlife management.

The United States Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act of 1954 is a United States statute. It has been amended several times.

The National Wildlife Refuge System in the United States has a long and distinguished history.

The Water Resources Development Act of 1986 is part of Pub. L. 99–662, a series of acts enacted by Congress of the United States on November 17, 1986.

Water Resources Development Act of 1988, Pub. L. 100–676, is a public law passed by Congress on November 17, 1988 concerning water resources in the United States in the areas of flood control, navigation, dredging, environment, recreation, water supply, beach nourishment and erosion.

Marine spatial planning (MSP) is a process that brings together multiple users of the ocean – including energy, industry, government, conservation and recreation – to make informed and coordinated decisions about how to use marine resources sustainably. MSP generally uses maps to create a more comprehensive picture of a marine area – identifying where and how an ocean area is being used and what natural resources and habitat exist. It is similar to land-use planning, but for marine waters.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) is a department within the government of Alaska. ADF&G's mission is to protect, maintain, and improve the fish, game, and aquatic plant resources of the state, and manage their use and development in the best interest of the economy and the well-being of the people of the state, consistent with the sustained yield principle. ADF&G manages approximately 750 active fisheries, 26 game management units, and 32 special areas. From resource policy to public education, the department considers public involvement essential to its mission and goals. The department is committed to working with tribes in Alaska and with a diverse group of State and Federal agencies. The department works cooperatively with various universities and nongovernmental organizations in formal and informal partnership arrangements, and assists local research or baseline environmental monitoring through citizen science programs.

The Water Resources Development Act of 1999, Pub. L. 106–53 (text)(PDF), was enacted by Congress of the United States on August 17, 1999. Most of the provisions of WRDA 1999 are administered by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

The Water Resources Development Act of 2000, Pub. L. 106–541 (text)(PDF), was enacted by Congress of the United States on December 11, 2000. Most of the provisions of WRDA 2000 are administered by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

The Arctic policy of the United States is the foreign policy of the United States in regard to the Arctic region. In addition, the United States' domestic policy toward Alaska is part of its Arctic policy.

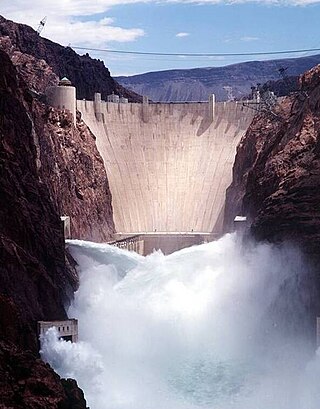

Hydropower policy in the United States includes all the laws, rules, regulations, programs and agencies that govern the national hydroelectric industry. Federal policy concerning waterpower developed over considerable time before the advent of electricity, and at times, has changed considerably, as water uses, available scientific technologies and considerations developed to the present day; over this period the priority of different, pre-existing and competing uses for water, flowing water and its energy, as well as for the water itself and competing available sources of energy have changed. Increased population and commercial demands spurred this developmental growth and many of the changes since, and these affect the technology's use today.

Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) was defined by the U.S. Congress in the 1996 amendments to the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, or Magnuson-Stevens Act, as "those waters and substrate necessary to fish for spawning, breeding, feeding or growth to maturity." Implementing regulations clarified that waters include all aquatic areas and their physical, chemical, and biological properties; substrate includes the associated biological communities that make these areas suitable for fish habitats, and the description and identification of EFH should include habitats used at any time during the species' life cycle. EFH includes all types of aquatic habitat, such as wetlands, coral reefs, sand, seagrasses, and rivers.

Over the past 200 years, the United States has lost more than 50% of its wetlands. And even with the current focus on wetland conservation, the US is losing about 60,000 acres (240 km2) of wetlands per year. However, from 1998 to 2004 the United States managed a net gain of 191,750 acres (776.0 km2) of wetlands . The past several decades have seen an increasing number of laws and regulations regarding wetlands, their surroundings, and their inhabitants, creating protections through several different outlets. Some of the most important have been and are the Migratory Bird Act, Swampbuster, and the Clean Water Act.

Rio Grande Silvery Minnow v. Bureau of Reclamation, called Rio Grande Silvery Minnow v. Keys in its earlier phases, was a case launched in 1999 by a group of environmentalists against the United States Bureau of Reclamation and the United States Army Corps of Engineers alleging violations of the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. The case resulted in significant changes to water and river management in the Middle Rio Grande Basin of New Mexico in an effort to reverse the damage that had been done to the habitat of two endangered species.

Sierra Club v. Babbitt, 15 F. Supp. 2d 1274, is a United States District Court for the Southern District of Alabama case in which the Sierra Club and several other environmental organizations and private citizens challenged the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). Plaintiffs filed action seeking declaratory injunctive relief regarding two incidental take permits (ITPs) issued by the FWS for the construction of two isolated high-density housing complexes in habitat of the endangered Alabama beach mouse. The District Court ruled that the FWS must reconsider its decision to allow high-density development on the Alabama coastline that might harm the endangered Alabama beach mouse. The District Court found that the FWS violated both the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) by permitting construction on the dwindling beach mouse habitat.

The Sportsmen’s Heritage And Recreational Enhancement Act of 2013 is an omnibus bill that covers several firearms, fishing, hunting, and federal land laws. H.R. 3590 would establish or amend certain laws related to the use of firearms and other recreational activities on federal lands. The bill also would authorize the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to permanently allow any state to provide hunting and conservation stamps for migratory birds. In addition, the bill would require the Secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture to charge an annual permit fee for small crews that conduct commercial filming activities on certain federal lands. Finally, the bill would require the Secretary of the Interior to issue permits to certain hunters seeking to import polar bear remains from Canada.

Conservation banking is an environmental market-based method designed to offset adverse effects, generally, to species of concern, are threatened, or endangered and protected under the United States Endangered Species Act (ESA) through the creation of conservation banks. Conservation banking can be viewed as a method of mitigation that allows permitting agencies to target various natural resources typically of value or concern, and it is generally contemplated as a protection technique to be implemented before the valued resource or species will need to be mitigated. The ESA prohibits the "taking" of fish and wildlife species which are officially listed as endangered or threatened in their populations. However, under section 7(a)(2) for Federal Agencies, and under section 10(a) for private parties, a take may be permissible for unavoidable impacts if there are conservation mitigation measures for the affected species or habitat. Purchasing “credits” through a conservation bank is one such mitigation measure to remedy the loss.

References

- ↑ Rosenberg, Ronald H. and Olson, Allen H., Federal Environmental Review Requirements Other than NEPA: The Emerging Challenge (1978). CLEVELAND STATE LAW REVIEW [Vol. 27: 195. 1978] FEDERAL ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW. Available from Faculty Publications. Paper 672. College of William and Mary Law School