Industrial waste is the waste produced by industrial activity which includes any material that is rendered useless during a manufacturing process such as that of factories, mills, and mining operations. Types of industrial waste include dirt and gravel, masonry and concrete, scrap metal, oil, solvents, chemicals, scrap lumber, even vegetable matter from restaurants. Industrial waste may be solid, semi-solid or liquid in form. It may be hazardous waste or non-hazardous waste. Industrial waste may pollute the nearby soil or adjacent water bodies, and can contaminate groundwater, lakes, streams, rivers or coastal waters. Industrial waste is often mixed into municipal waste, making accurate assessments difficult. An estimate for the US goes as high as 7.6 billion tons of industrial waste produced annually, as of 2017. Most countries have enacted legislation to deal with the problem of industrial waste, but strictness and compliance regimes vary. Enforcement is always an issue.

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Its objective is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters; recognizing the responsibilities of the states in addressing pollution and providing assistance to states to do so, including funding for publicly owned treatment works for the improvement of wastewater treatment; and maintaining the integrity of wetlands.

S. D. Warren Co. v. Maine Board of Environmental Protection, 547 U.S. 370 (2006), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States involving licensing requirements under the Clean Water Act. The Court ruled unanimously that hydroelectric dams were subject to section 401 of the Act, which conditioned federal licensing for a licensed activity that could result in "any discharge" into navigable waters upon the receipt of a state certification that water protection laws would not be violated. The Court believed that since the Act did not define the word "discharge" it should be given its ordinary meaning, such that the simple flowing forth of water from a dam qualified.

Pebble Mine is the common name of a proposed copper-gold-molybdenum mining project in the Bristol Bay region of Southwest Alaska, near Lake Iliamna and Lake Clark. It was discovered in 1987, optioned by Northern Dynasty Minerals in 2001, explored in 2002, and drilled from 2002-2013 with discovery in 2005. Preparing for the permitting process began and administrative review lasted over 13 years.

The Clean Water Protection Act was a bill introduced in the 111th United States Congress via the House of Representatives Subcommittee on Water Resources and Environment, of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. It proposed to redefine "fill material" to not include mining "waste" under the Federal Water Pollution Control Act.

The Juneau mining district is a gold mining area in the U.S. state of Alaska.

The Marcopper mining disaster is one of the worst mining and environmental disasters in Philippine history. It occurred on March 24, 1996, on the Philippine island of Marinduque, a province of the Philippines located in the Mimaropa region. The disaster led to drastic reforms in the country's mining policy.

The Alaska Clean Water Initiative (ACWI) of 2008 was a citizens-initiative ballot measure. In Alaska, such measures become state law, if a majority of voters vote in favor of the measure. The ACWI contained regulatory language limiting the release and distribution of "sulfide mining" effluents and products into the environment. In August 2008, Ballot Measure 4, the "Alaska Clean Water Initiative," was voted down in the statewide primary election.

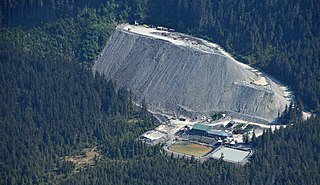

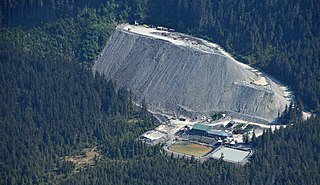

Kensington mine is a gold mine located 45 mi (72 km) north of Juneau, Alaska. The mine is owned by Coeur Alaska Inc., a subsidiary company of Coeur Mining.

Lower Slate Lake is a lake in the State of Alaska in the Tongass National Forest. It is designated as the disposal site for the tailings from Coeur Alaska's Kensington mine. Lower Slate Lake is 1.38 mi (2.22 km) away from Berners Bay.

Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County (SWANCC) v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 531 U.S. 159 (2001), was a decision by the US Supreme Court that interpreted a provision of the Clean Water Act. Section 404 of the Act requires permits for the discharge of dredged or fill materials into "navigable waters," which is defined by the Act as "waters of the United States." That provision was the basis for the federal wetlands-permitting program.

Alaska Dept. of Environmental Conservation v. EPA, 540 U.S. 461 (2004), is a US Supreme Court case clarifying the scope of state environmental regulators and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court found the EPA has authority to overrule state agency decisions under the Clean Air Act that a company is using the "best available controlling technology" to prevent pollution.

Point source water pollution comes from discrete conveyances and alters the chemical, biological, and physical characteristics of water. In the United States, it is largely regulated by the Clean Water Act (CWA). Among other things, the Act requires dischargers to obtain a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit to legally discharge pollutants into a water body. However, point source pollution remains an issue in some water bodies, due to some limitations of the Act. Consequently, other regulatory approaches have emerged, such as water quality trading and voluntary community-level efforts.

Los Angeles County Flood Control District v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 568 U.S. 78 (2013), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Natural Resources Defense Council and Santa Monica Baykeeper challenged the Los Angeles County Flood Control District (District) for violating the terms of its National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit as shown in water quality measurements from monitoring stations within the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers. The Supreme Court, by a unanimous 9-0 vote, reversed and remanded the Ninth Circuit's ruling on the grounds that the flow of water from an improved portion of a navigable waterway into an unimproved portion of the same waterway does not qualify as a "discharge of a pollutant" under the Clean Water Act.

XS Platinum Inc., also known as XSP, is a wholly owned subsidiary of XS Platinum Ltd, and was founded in 2007 to be a sustainable mine that would get its platinum from mining waste as opposed to new mining. XSP had a contract with Tiffany & Co. On May 1, 2009, the BLM authorized the disposal of 200,000 cubic yards of processed tailing material as mineral materials from the following mining claims in the vicinity of Platinum, Alaska within the Togiak National Wildlife Refuge. At its beginning, day-to-day operations were to be under the direction of Phil Cash, a metallurgical engineer.

The Clean Water Rule is a 2015 regulation published by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to clarify water resource management in the United States under a provision of the Clean Water Act of 1972. The regulation defined the scope of federal water protection in a more consistent manner, particularly over streams and wetlands which have a significant hydrological and ecological connection to traditional navigable waters, interstate waters, and territorial seas. It is also referred to as the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) rule, which defines all bodies of water that fall under U.S. federal jurisdiction. The rule was published in response to concerns about lack of clarity over the act's scope from legislators at multiple levels, industry members, researchers and other science professionals, activists, and citizens.

United States of America v. Reserve Mining Company, 408 F. Supp. 1212, was a United States District Court for the District of Minnesota case that determined the Reserve Mining Company was responsible for amphibole asbestos fibers found in the public drinking water of Duluth, Minnesota and other North Shore (Minnesota) communities.

The Southeast Alaska Conservation Council (SEACC) is a non-profit organization that focuses on protecting the lands and waters of Southeast Alaska. They promote conservation and advocate for sustainable natural resource management. SEACC is located in the capital city of Alaska, Juneau. The environmental organization focuses on concerns in the Southeast region of Alaska, including the areas of the Panhandle, the Tongass National Forest, and the Inside Passage.

County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund, No. 18-260, 590 U.S. ___ (2020), was a United States Supreme Court case involving pollution discharges under the Clean Water Act (CWA). The case asked whether the Clean Water Act requires a permit when pollutants that originate from a non-point source can be traced to reach navigable waters through mechanisms such as groundwater transport. In a 6–3 decision, the Court ruled that such non-point discharges require a permit when they are the "functional equivalent of a direct discharge", a new test defined by the ruling. The decision vacated the ruling of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and remanded the case with instructions to apply the new standard to the lower courts with cooperation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

New Jersey Water Pollution Control Law consists of legislative and regulatory measures intended to limit the amount of harmful substances found in the state's lakes, rivers, and groundwater. In New Jersey, the federal Clean Water Act and the state Water Pollution Control Act are the most significant pieces of water pollution control legislation. These laws are implemented and enforced by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP).