Mining is the extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agricultural processes, or feasibly created artificially in a laboratory or factory. Ores recovered by mining include metals, coal, oil shale, gemstones, limestone, chalk, dimension stone, rock salt, potash, gravel, and clay. The ore must be a rock or mineral that contains valuable constituent, can be extracted or mined and sold for profit. Mining in a wider sense includes extraction of any non-renewable resource such as petroleum, natural gas, or even water.

A slurry pipeline is a specially engineered pipeline used to move ores, such as coal or iron, or mining waste, called tailings, over long distances. A mixture of the ore concentrate and water, called slurry, is pumped to its destination and the water is filtered out. Due to the abrasive properties of slurry, the pipelines can be lined with high-density polyethylene (HDPE), or manufactured completely from HDPE Pipe, although this requires a very thick pipe wall. Slurry pipelines are used as an alternative to railroad transportation when mines are located in remote, inaccessible areas.

Open-pit mining, also known as open-cast or open-cut mining and in larger contexts mega-mining, is a surface mining technique that extracts rock or minerals from the earth using a pit, sometimes known as a borrow pit.

Industrial wastewater treatment describes the processes used for treating wastewater that is produced by industries as an undesirable by-product. After treatment, the treated industrial wastewater may be reused or released to a sanitary sewer or to a surface water in the environment. Some industrial facilities generate wastewater that can be treated in sewage treatment plants. Most industrial processes, such as petroleum refineries, chemical and petrochemical plants have their own specialized facilities to treat their wastewaters so that the pollutant concentrations in the treated wastewater comply with the regulations regarding disposal of wastewaters into sewers or into rivers, lakes or oceans. This applies to industries that generate wastewater with high concentrations of organic matter, toxic pollutants or nutrients such as ammonia. Some industries install a pre-treatment system to remove some pollutants, and then discharge the partially treated wastewater to the municipal sewer system.

Froth flotation is a process for selectively separating hydrophobic materials from hydrophilic. This is used in mineral processing, paper recycling and waste-water treatment industries. Historically this was first used in the mining industry, where it was one of the great enabling technologies of the 20th century. It has been described as "the single most important operation used for the recovery and upgrading of sulfide ores". The development of froth flotation has improved the recovery of valuable minerals, such as copper- and lead-bearing minerals. Along with mechanized mining, it has allowed the economic recovery of valuable metals from much lower-grade ore than previously.

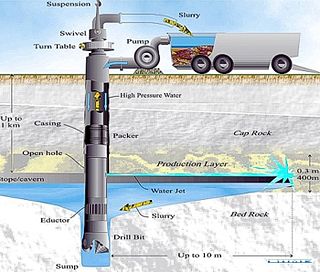

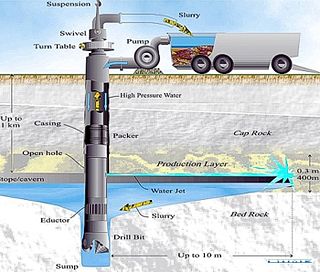

Borehole Mining (BHM) is a remote operated method of extraction (mining) of mineral resources through boreholes based on in-situ conversion of ores into a mobile form (slurry) by means of high pressure water jetting (hydraulicking). This process is carried-out from a land surface, open pit floor, underground mine or floating vessel through pre-drilled boreholes.

Mineral processing is the process of separating commercially valuable minerals from their ores in the field of extractive metallurgy. Depending on the processes used in each instance, it is often referred to as ore dressing or ore milling.

Surface mining, including strip mining, open-pit mining and mountaintop removal mining, is a broad category of mining in which soil and rock overlying the mineral deposit are removed, in contrast to underground mining, in which the overlying rock is left in place, and the mineral is removed through shafts or tunnels.

Bottom ash is part of the non-combustible residue of combustion in a power plant, boiler, furnace or incinerator. In an industrial context, it has traditionally referred to coal combustion and comprises traces of combustibles embedded in forming clinkers and sticking to hot side walls of a coal-burning furnace during its operation. The portion of the ash that escapes up the chimney or stack is, however, referred to as fly ash. The clinkers fall by themselves into the bottom hopper of a coal-burning furnace and are cooled. The above portion of the ash is also referred to as bottom ash.

A coal preparation plant is a facility that washes coal of soil and rock, crushes it into graded sized chunks (sorting), stockpiles grades preparing it for transport to market, and more often than not, also loads coal into rail cars, barges, or ships.

A tailings dam is typically an earth-fill embankment dam used to store byproducts of mining operations after separating the ore from the gangue. Tailings can be liquid, solid, or a slurry of fine particles, and are usually highly toxic and potentially radioactive. Solid tailings are often used as part of the structure itself.

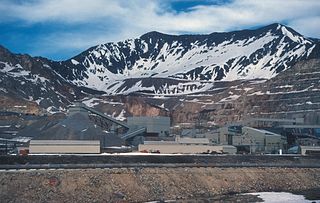

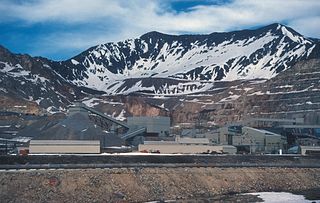

The Climax mine, located in Climax, Colorado, United States, is a major molybdenum mine in Lake and Summit counties, Colorado. Shipments from the mine began in 1915. At its highest output, the Climax mine was the largest molybdenum mine in the world, and for many years it supplied three quarters of the world's supply of molybdenum.

The Batu Hijau mine is an open pit copper-gold mine operated by PT. Amman Mineral Nusa Tenggara. The mine is the second largest copper-gold mine in Indonesia behind the Grasberg mine of PT. Freeport Indonesia. The mine is located 1,530 kilometres (950 mi) east of the Indonesian capital Jakarta on Sumbawa, an island in West Nusa Tenggara Province, more precisely in the southern part of West Sumbawa Regency. The mine is the result of a ten-year exploration and construction program based on a 1999 discovery of the porphyry copper deposit. Production began in 2000.

Environmental effects of mining can occur at local, regional, and global scales through direct and indirect mining practices. Mining can cause erosion, sinkholes, loss of biodiversity, or the contamination of soil, groundwater, and surface water by chemicals emitted from mining processes. These processes also affect the atmosphere through carbon emissions which contributes to climate change. Some mining methods may have such significant environmental and public health effects that mining companies in some countries are required to follow strict environmental and rehabilitation codes to ensure that the mined area returns to its original state. Mining can provide various advantages to societies, yet it can also spark conflicts, particularly regarding land use both above and below the surface.

An ash pond, also called a coal ash basin or surface impoundment, is an engineered structure used at coal-fired power stations for the disposal of two types of coal combustion products: bottom ash and fly ash. The pond is used as a landfill to prevent the release of ash into the atmosphere. Although the use of ash ponds in combination with air pollution controls decreases the amount of airborne pollutants, the structures pose serious health risks for the surrounding environment.

Rampura Agucha is a zinc and lead mine located on a massive sulfide deposit in the Bhilwara district of Rajasthan, India. Rampura Agucha is located 220 km (140 mi) from Jaipur. It is north of Bhilwara, and northwest of Shahpura. Rampura Agucha is 10 km (6.2 mi) southeast of Gulabpura on NH 79. The mine is owned by Hindustan Zinc Limited (HZL), and has the world's largest deposits of zinc and lead.

Mount Polley mine is a Canadian gold and copper mine located in British Columbia near the towns of Williams Lake and Likely. It consists of two open-pit sites with an underground mining component and is owned and operated by the Mount Polley Mining Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Imperial Metals. In 2013, the mine produced an output of 38,501,165 pounds (17,463,835 kg) of copper, 45,823 ounces of gold, and 123,999 of silver. The mill commenced operations in 1997 and was closed and placed on care and maintenance in 2019. The company owns 20,113 hectares (201.13 km2) of property near Quesnel Lake and Polley Lake where it has mining leases and operations on 2,007 hectares (20.07 km2) and mineral claims on 18,106 hectares (181.06 km2). Mineral concentrate is delivered by truck to the Port of Vancouver.

Red mud, now more frequently termed bauxite residue, is an industrial waste generated during the processing of bauxite into alumina using the Bayer process. It is composed of various oxide compounds, including the iron oxides which give its red colour. Over 95% of the alumina produced globally is through the Bayer process; for every tonne of alumina produced, approximately 1 to 1.5 tonnes of red mud are also produced. Annual production of alumina in 2020 was over 133 million tonnes resulting in the generation of over 175 million tonnes of red mud.

The environmental impact of Iron ore mining in all its phases from excavation to beneficiation to transportation may have detrimental effects on air quality, water quality, and biological species. This is a result of the large-scale iron ore tailings that are released into the environment which are harmful to both animals and humans.

The structural failure of tailings dams and the ensuing release of toxic metals in the environment is a great concern. The standard of public reporting on tailings dam incidents is poor. A large number remain completely unreported, or lack basic facts when reported. There is no comprehensive database for historic failures. According to mining engineer David M Chambers of the Center for Science in Public Participation, 10,000 years is "a conservative estimate" of how long most tailings dams will need to maintain structural integrity.