Tropical Storm Ana was the first named storm of the 2003 Atlantic hurricane season. A pre-season storm, it developed initially as a subtropical cyclone from a non-tropical low on April 20 to the west of Bermuda. It tracked east-southeastward and organized, and on April 21 it transitioned into a tropical cyclone with peak winds of 60 mph (97 km/h). Tropical Storm Ana turned east-northeastward, steadily weakening due to wind shear and an approaching cold front, and on April 24 it became an extratropical cyclone. The storm brushed Bermuda with light rain, and its remnants produced precipitation in the Azores and the United Kingdom. Swells generated by the storm capsized a boat along the Florida coastline, causing two fatalities.

Subtropical Storm Nicole was the first subtropical storm to receive a name using the standard hurricane name list that did not become a tropical cyclone. The fifteenth tropical or subtropical cyclone and fourteenth named storm of the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season, Nicole developed on October 10 near Bermuda from a broad surface low that developed as a result of the interaction between an upper level trough and a decaying cold front. The storm turned to the northeast, passing close to Bermuda as it intensified to reach peak winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) on October 11. Deep convection developed near the center of the system as it attempted to become a fully tropical cyclone. However, it failed to do so and was absorbed by an extratropical cyclone late on October 11.

The 2011 Pacific hurricane season was a below average season in terms of named storms, although it had an above average number of hurricanes and major hurricanes. During the season, 13 tropical depressions formed along with 11 tropical storms, 10 hurricanes and 6 major hurricanes. The season officially began on May 15 in the East Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Pacific basin. The season's first cyclone, Hurricane Adrian formed on June 7, and the last, Hurricane Kenneth, dissipated on November 25.

The 2012 Pacific hurricane season was a moderately active Pacific hurricane season that saw an unusually high number of tropical cyclones pass west of the Baja California Peninsula. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the central Pacific (from 140°W to the International Date Line, north of the equator; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in these regions of the Pacific Ocean. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year. This season's first system, Tropical Storm Aletta, formed on May 14, and the last, Tropical Storm Rosa, dissipated on November 3.

Hurricane Fred was one of the easternmost forming major hurricanes in the North Atlantic basin since satellite observations became available. Forming out of a strong tropical wave on September 7, 2009 near the Cape Verde Islands, Fred gradually organized within an area of moderate wind shear. The following day, decreasing shear allowed the storm to intensify and develop well-organized convective banding features. Later on September 8, Fred attained hurricane intensity and underwent rapid intensification overnight, attaining its peak intensity as a strong Category 3 hurricane with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 958 mbar. Shortly after reaching this intensity, the hurricane began to weaken as wind shear increased and dry air hampered convective development.

The 2016 Pacific hurricane season was tied as the fifth-most active Pacific hurricane season on record, alongside the 2014 season. Throughout the course of the year, a total of 22 named storms, 13 hurricanes and six major hurricanes were observed within the basin. Although the season was very active, it was considerably less active than the previous season, with large gaps of inactivity at the beginning and towards the end of the season. It officially started on May 15 in the Eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific ; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in these regions of the Pacific Ocean. However, tropical development is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of Hurricane Pali on January 7, the earliest Central Pacific tropical cyclone on record. After Pali, however, no tropical cyclones developed in either region until a short-lived depression on June 6. Also, there were no additional named storms until July 2, when Tropical Storm Agatha formed, becoming the latest first-named Eastern Pacific tropical storm since Tropical Storm Ava in 1969.

Hurricane Richard was a damaging tropical cyclone that affected areas of Central America in October 2010. It developed on October 20 from an area of low pressure that had stalled in the Caribbean Sea. The system moved to the southeast before turning to the west. The storm slowly organized, and the system intensified into a tropical storm. Initially, Richard only intensified slowly in an area of weak steering currents. However, by October 23, wind shear diminished, and the storm intensified faster as it headed toward Belize. The next day, Richard intensified into hurricane status, and further into its peak intensity as a Category 2 hurricane, reaching maximum winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). The hurricane made its only landfall on Belize at peak intensity. Over land, Richard quickly weakened, and later degenerated into a remnant low on October 25.

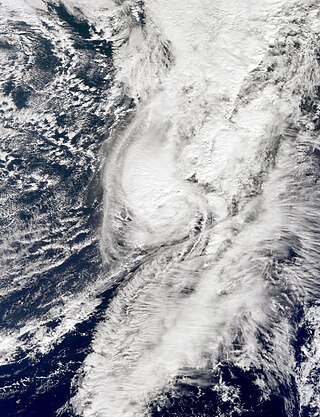

Hurricane Shary was a short-lived tropical cyclone that stayed over the open waters of the North Atlantic in late October 2010. The eighteenth named storm and eleventh hurricane of the unusually active 2010 Atlantic hurricane season, Shary originated from a weak area of convection over the Central Atlantic and became a tropical storm on October 28. Initially not expected to exceed wind speeds of 50 mph (85 km/h), Shary defied predictions and became a minimal hurricane on October 30, passing well east of Bermuda. Unfavorable conditions subsequently impacted the storm, and Shary quickly began to lose tropical characteristics. Later that day, Shary degenerated into a post-tropical cyclone, and the final advisory by the National Hurricane Center was issued.

Hurricane Adrian was an intense, albeit short-lived early-season Category 4 hurricane that brought heavy rainfall and high waves to Mexico in June 2011 during the 2011 Pacific hurricane season. Adrian originated from an area of disturbed weather which had developed during the course of early June, off the Pacific coast of Mexico. On June 7, it acquired a sufficiently organized structure with deep convection to be classified as a tropical cyclone, and the National Hurricane Center (NHC) designated it as Tropical Depression One-E, the first one of 2011. It further strengthened to be upgraded into a tropical storm later that day. Adrian moved rather slowly; briefly recurving northward after being caught in the steering winds. After steady intensification, it was upgraded into a hurricane on June 9. The storm subsequently entered a phase of rapid intensification, developing a distinct eye with good outflow in all quadrants. Followed by this period of rapid intensification, it obtained sustained winds fast enough to be considered a major hurricane and reached its peak intensity as a category 4 hurricane that evening.

Hurricane Katia was a fairly intense Cape Verde hurricane that had substantial impact across Europe as a post-tropical cyclone. The eleventh named storm, second hurricane, and second major hurricane of the active 2011 Atlantic hurricane season, Katia originated as a tropical depression from a tropical wave over the eastern Atlantic on August 29. It intensified into a tropical storm the following day and further developed into a hurricane by September 1, although unfavorable atmospheric conditions hindered strengthening thereafter. As the storm began to recurve over the western Atlantic, a more hospitable regime allowed Katia to become a major hurricane by September 5 and peak as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) that afternoon. Internal core processes, increased wind shear, an impinging cold front, and increasingly cool ocean temperatures all prompted the cyclone to weaken almost immediately after peak, and Katia ultimately transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 10.

The 2016 Atlantic hurricane season was the deadliest Atlantic hurricane season since 2008, and the first above-average hurricane season since 2012, producing 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes and 4 major hurricanes. The season officially started on June 1 and ended on November 30, though the first storm, Hurricane Alex which formed in the Northeastern Atlantic, developed on January 12, being the first hurricane to develop in January since 1938. The final storm, Otto, crossed into the Eastern Pacific on November 25, a few days before the official end. Following Alex, Tropical Storm Bonnie brought flooding to South Carolina and portions of North Carolina. Tropical Storm Colin in early June brought minor flooding and wind damage to parts of the Southeastern United States, especially Florida. Hurricane Earl left 94 fatalities in the Dominican Republic and Mexico, 81 of which occurred in the latter. In early September, Hurricane Hermine, the first hurricane to make landfall in Florida since Hurricane Wilma in 2005, brought extensive coastal flooding damage especially to the Forgotten and Nature coasts of Florida. Hermine was responsible for five fatalities and about $550 million (2016 USD) in damage.

Hurricane Raymond was a category 3 major hurricane which briefly threatened the southwestern coast of Mexico before recurving back out to sea. The seventeenth named storm, eighth hurricane, and only major hurricane of the 2013 Pacific hurricane season, Raymond developed from a tropical wave on October 20 south of Acapulco, Mexico. Within favorable conditions for tropical cyclogenesis, Raymond quickly intensified, attaining tropical storm intensity and later hurricane intensity within a day of cyclogenesis. On October 21, the hurricane reached its peak intensity with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h). A blocking ridge forced the hurricane to the southwest, while at the same time Raymond began to quickly weaken due to wind shear. The following day, the tropical cyclone weakened to tropical storm status. After tracking westward, Raymond reentered more favorable conditions, allowing it to intensify back to hurricane strength on October 27 while curving northward. The hurricane reached a secondary peak intensity with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) several hours later. Deteriorating atmospheric conditions resulted in Raymond weakening for a final time, and on October 30, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) declared the tropical cyclone to have dissipated.

Hurricane Marie is tied as the seventh-most intense Pacific hurricane on record, attaining a barometric pressure of 918 mbar in August 2014. The fourteenth named storm, ninth hurricane, and sixth major hurricane of the season, Marie began as a tropical wave that emerged off the west coast of Africa over the Atlantic Ocean on August 10. Some organization of shower and thunderstorm activity initially took place, but dry air soon impinged upon the system and imparted weakening. The wave tracked westward across the Atlantic and Caribbean for several days. On August 19, an area of low pressure consolidated within the wave west of Central America. With favorable atmospheric conditions, convective activity and banding features increased around the system and by August 22, the system acquired enough organization to be classified as Tropical Depression Thirteen-E while situated about 370 mi (595 km) south-southeast of Acapulco, Mexico. Development was initially fast-paced, as the depression acquired tropical storm-force winds within six hours of formation and hurricane-force by August 23. However, due to some vertical wind shear its intensification rate stalled, and for a time it remained a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.

Hurricane Fay was the first hurricane to make landfall on Bermuda since Emily in 1987. The sixth named storm and fifth hurricane of the 2014 Atlantic hurricane season, Fay evolved from a broad disturbance several hundred miles northeast of the Lesser Antilles on October 10. Initially a subtropical cyclone with an expansive wind field and asymmetrical cloud field, the storm gradually attained tropical characteristics as it turned north, transitioning into a tropical storm early on October 11.

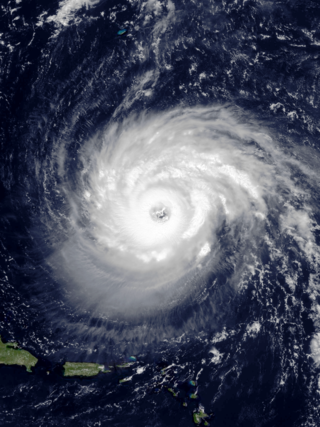

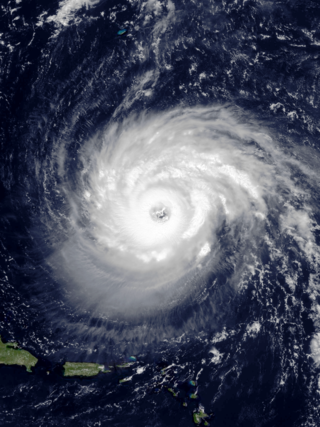

Hurricane Joaquin was a powerful tropical cyclone that devastated several districts of The Bahamas and caused damage in the Turks and Caicos Islands, parts of the Greater Antilles, and Bermuda. It was also the strongest Atlantic hurricane of non-tropical origin recorded in the satellite era. The tenth named storm, third hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 2015 Atlantic hurricane season, Joaquin evolved from a non-tropical low to become a tropical depression on September 28, well southwest of Bermuda. Tempered by unfavorable wind shear, the depression drifted southwestward. After becoming a tropical storm the next day, Joaquin underwent rapid intensification, reaching hurricane status on September 30 and Category 4 major hurricane strength on October 1. Meandering over the southern Bahamas, Joaquin's eye passed near or over several islands. On October 3, the hurricane weakened somewhat and accelerated to the northeast. Abrupt re-intensification ensued later that day, and Joaquin acquired sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h), just short of Category 5 strength.

Hurricane Paulette was a strong and long-lived Category 2 Atlantic hurricane which became the first to make landfall in Bermuda since Hurricane Gonzalo did so in 2014. The sixteenth named storm and sixth hurricane of the record-breaking 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, Paulette developed from a tropical wave that left the coast of Africa on September 2. The wave eventually consolidated into a tropical depression on September 7. Paulette fluctuated in intensity over the next few days, due to strong wind shear, initially peaking as a strong tropical storm on September 8. It eventually strengthened into a hurricane early on September 13 as shear decreased. On September 14, Paulette made landfall in northeastern Bermuda as a Category 2 hurricane, while making a gradual turn to the northeast. The cyclone further strengthened as it moved away from the island, reaching its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 105 mph (169 km/h) and a minimum central atmospheric pressure of 965 mbar (28.5 inHg) on September 14. On the evening of September 15, Paulette began to weaken and undergo extratropical transition, which it completed on September 16. The hurricane's extratropical remnants persisted and moved southward then eastward, and eventually, Paulette regenerated into a tropical storm early on September 20 south of the Azores– which resulted in the U.S National Weather Service coining the phrase "zombie storm" to describe its unusual regeneration. Paulette's second phase proved short-lived, however, as the storm quickly weakened and became post-tropical again two days later. The remnant persisted for several days before dissipating south of the Azores on September 28. In total, Paulette was a tropical cyclone for 11.25 days, and the system had an overall lifespan of 21 days.

Hurricane Teddy was a large and powerful Cape Verde hurricane that was the fifth-largest Atlantic hurricane by diameter of gale-force winds recorded. Teddy produced large swells along the coast of the Eastern United States and Atlantic Canada in September 2020. The twentieth tropical depression, nineteenth named storm, eighth hurricane, and second major hurricane of the record-breaking 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, Teddy initially formed from a tropical depression that developed from a tropical wave on September 12. Initially, the depression's large size and moderate wind shear kept it from organizing, but it eventually intensified into Tropical Storm Teddy on September 14. After steadily intensifying for about a day, the storm rapidly became a Category 2 hurricane on September 16 before westerly wind shear caused a temporary pause in the intensification trend. It then rapidly intensified again on September 17 and became a Category 4 hurricane. Internal fluctuations and eyewall replacement cycles then caused the storm to fluctuate in intensity before it weakened some as it approached Bermuda. After passing east of the island as a Category 1 hurricane on September 21, Teddy restrengthened back to Category 2 strength due to baroclinic forcing. It weakened again to Category 1 strength the next day before becoming post-tropical as it approached Atlantic Canada early on September 23. It then weakened to a gale-force low and made landfall in Nova Scotia with sustained winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). The system weakened further as it moved northward across eastern Nova Scotia and then the Gulf of St. Lawrence, before being absorbed by a larger non-tropical low early on September 24, near eastern Labrador.

Hurricane Epsilon was a strong tropical cyclone that affected Bermuda, and parts of North America and Western Europe. The twenty-seventh tropical or subtropical cyclone, twenty-sixth named storm, eleventh hurricane, and fourth major hurricane of the extremely-active 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, Epsilon had a non-tropical origin, developing from an upper-level low off the East Coast of the United States on October 13. The low gradually organized, becoming Tropical Depression Twenty-Seven on October 19, and six hours later, Tropical Storm Epsilon. The storm executed a counterclockwise loop before turning westward, while strengthening. On October 20, Epsilon began undergoing rapid intensification, becoming a Category 1 hurricane on the next day, before peaking as a Category 3 major hurricane on October 22, with maximum 1-minute sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 952 millibars (28.1 inHg). This made Epsilon the easternmost major hurricane this late in the calendar year, as well as the strongest late-season major hurricane in the northeastern Atlantic, and the fastest recorded case of a tropical cyclone undergoing rapid intensification that far northeast that late in the hurricane season. Afterward, Epsilon began to weaken as the system turned northward, with the storm dropping to Category 1 intensity late that day. Epsilon maintained its intensity as it moved northward, passing to the east of Bermuda. On October 24, Epsilon turned northeastward and gradually accelerated, before weakening into a tropical storm on the next day. On October 26, Epsilon transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, before being absorbed by another larger extratropical storm later that same day.

Hurricane Sam was a powerful and long-lived Cape Verde hurricane that threatened Bermuda, lasting from late September through early October. It was the fifth longest-lasting intense Atlantic hurricane, as measured by accumulated cyclone energy, since reliable records began in 1966. Sam was the eighteenth named storm, seventh hurricane, and fourth major hurricane of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season.

Hurricane Earl was a large, long-lived Category 2 hurricane that brought heavy rain to Puerto Rico and Newfoundland in September 2022 despite remaining mostly out to sea. The fifth named storm and second hurricane of the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season, Earl originated from a tropical wave that moved off the coast of Africa on August 25. The wave struggled to develop over the next week as it moved west-northwestward in a marginally conducive environment. Eventually, the system was able to organize into Tropical Storm Earl on September 3. The storm passed through parts of the Caribbean, but strong wind shear initially halted Earl from intensifying and it maintained tropical storm status. The storm then turned northward into a more favorable environment and started to intensify. Earl eventually reached Category 2 hurricane status, before repeated dry air entrainments caused the storm to fluctuate in intensity. Earl reached peak winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) before quickly becoming extratropical off the coast of Newfoundland on September 10. It continued moving northeast before dissipating on September 15.