Hurricane Donna, known in Puerto Rico as Hurricane San Lorenzo, was the strongest hurricane of the 1960 Atlantic hurricane season, and caused severe damage to the Lesser Antilles, the Greater Antilles, and the East Coast of the United States, especially Florida, in August–September. The fifth tropical cyclone, third hurricane, and first major hurricane of the season, Donna developed south of Cape Verde on August 29, spawned by a tropical wave to which 63 deaths from a plane crash in Senegal were attributed. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Donna by the following day. Donna moved west-northwestward at roughly 20 mph (32 km/h) and by September 1, it reached hurricane status. Over the next three days, Donna deepened significantly and reached maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) on September 4. Thereafter, it maintained intensity as it struck the Lesser Antilles later that day. On Sint Maarten, the storm left a quarter of the island's population homeless and killed seven people. An additional five deaths were reported in Anguilla, and there were seven other fatalities throughout the Virgin Islands. In Puerto Rico, severe flash flooding led to 107 fatalities, 85 of them in Humacao alone.

Hurricane Jeanne was a Category 3 hurricane that struck the Caribbean and the Eastern United States in September 2004. It was the deadliest hurricane in the Atlantic basin since Mitch in 1998. It was the tenth named storm, the seventh hurricane, and the fifth major hurricane of the season, as well as the third hurricane and fourth named storm of the season to make landfall in Florida. After wreaking havoc on Hispaniola, Jeanne struggled to reorganize, eventually strengthening and performing a complete loop over the open Atlantic. It headed westwards, strengthening into a Category 3 hurricane and passing over the islands of Great Abaco and Grand Bahama in the Bahamas on September 25. Jeanne made landfall later in the day in Florida just two miles from where Hurricane Frances had struck a mere three weeks earlier.

Hurricane David was a devestating Atlantic hurricane which caused massive loss of life in the Dominican Republic in August 1979, and was the most intense hurricane to make landfall in the country in recorded history. A long-lived Cape Verde hurricane, David was the fourth named storm, second hurricane, and first major hurricane of the 1979 Atlantic hurricane season.

The 1945 Atlantic hurricane season produced multiple landfalling tropical cyclones. It officially began on June 16 and lasted until October 31, dates delimiting the period when a majority of storms were perceived to form in the Atlantic Ocean. A total of 11 systems were documented, including a late-season cyclone retroactively added a decade later. Five of the eleven systems intensified into hurricanes, and two further attained their peaks as major hurricanes. Activity began with the formation of a tropical storm in the Caribbean on June 20, which then made landfalls in Florida and North Carolina at hurricane intensity, causing one death and at least $75,000 in damage. In late August, a Category 3 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale struck the Texas coastline, with 3 deaths and $20.1 million in damage. The most powerful hurricane of the season, reaching Category 4 intensity, wrought severe damage throughout the Bahamas and East Coast of the United States, namely Florida, in mid-September; 26 people were killed and damage reached $60 million. A hurricane moved ashore the coastline of Belize in early October, causing one death, while the final cyclone of the year resulted in 5 deaths and $2 million in damage across Cuba and the Bahamas two weeks later. Overall, 36 people were killed and damage reached at least $82.85 million.

The 1933 Atlantic hurricane season is the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record in terms of accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), with a total of 259. It also set a record for nameable tropical storms in a single season, 20, which stood until 2005, when there were 28 storms. The season ran for six months of 1933, with tropical cyclone development occurring as early as May and as late as November. A system was active for all but 13 days from June 28 to October 7.

The 1932 Atlantic hurricane season featured several powerful storms, including the Cuba hurricane, which remains the deadliest tropical cyclone in the history of Cuba and among the most intense to strike the island nation. It was a relatively active season, with fifteen known storms, six hurricanes, and four major hurricanes. However, tropical cyclones that did not approach populated areas or shipping lanes, especially if they were relatively weak and of short duration, may have remained undetected. Because technologies such as satellite monitoring were not available until the 1960s, historical data on tropical cyclones from this period are often not reliable. The Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project discovered four new tropical cyclones, all of which were tropical storms, that occurred during the year. Two storms attained Category 5 intensity, the first known occurrence in which multiple Category 5 hurricanes formed in the same year. The season's first cyclone developed on May 5, while the last remaining system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by November 13.

The 1928 Atlantic hurricane season was a near average hurricane season in which seven tropical cyclones developed. Of these, six intensified into a tropical storm and four further strengthened into hurricanes. One hurricane deepened into a major hurricane, which is Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale. The first system, the Fort Pierce hurricane, developed near the Lesser Antilles on August 3. The storm crossed the Bahamas and made landfall in Florida. Two fatalities and approximately $235,000 in damage was reported. A few days after the first storm developed, the Haiti hurricane, formed near the southern Windward Islands on August 7. The storm went on to strike Haiti, Cuba, and Florida. This storm left about $2 million in damage and at least 210 deaths. Impacts from the third system are unknown.

The Okeechobee hurricane of 1928, also known as the San Felipe Segundo hurricane, was one of the deadliest hurricanes in the recorded history of the North Atlantic basin, and the fourth deadliest hurricane in the United States, only behind the 1900 Galveston hurricane, 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane, and Hurricane Maria. The hurricane killed an estimated 2,500 people in the United States; most of the fatalities occurred in the state of Florida, particularly in Lake Okeechobee. It was the fourth tropical cyclone, third hurricane, and only major hurricane of the 1928 Atlantic hurricane season. It developed off the west coast of Africa on September 6 as a tropical depression, but it strengthened into a tropical storm later that day, shortly before passing south of the Cape Verde islands. Further intensification was slow and halted late on September 7. About 48 hours later, the storm strengthened and became a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Still moving westward, the system reached Category 4 intensity before striking Guadeloupe on September 12, where it brought great destruction and resulted in 1,200 deaths. The islands of Martinique, Montserrat, and Nevis also reported damage and fatalities, but not nearly as severe as in Guadeloupe.

Hurricane Erin was the first hurricane to strike the contiguous United States since Hurricane Andrew in 1992. The fifth tropical cyclone, fifth named storm, and second hurricane of the unusually active 1995 Atlantic hurricane season, Erin developed from a tropical wave near the southeastern Bahamas on July 31. Moving northwestward, the cyclone intensified into a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale near Rum Cay about 24 hours later. After a brief jog to the north-northwest on August 1, Erin began moving to the west-northwest. The cyclone then moved over the northwestern Bahamas, including the Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama. Early on August 2, Erin made landfall near Vero Beach, Florida, with winds of 85 mph (137 km/h). The hurricane weakened while crossing the Florida peninsula and fell to tropical storm intensity before emerging into the Gulf of Mexico later that day.

The 1944 Cuba–Florida hurricane was a large Category 4 tropical cyclone on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale that caused widespread damage across the western Caribbean Sea and Southeastern United States in October 1944. It inflicted over US$100 million in damage and caused at least 318 deaths, the majority of fatalities occurring in Cuba. One study suggested that an equivalent storm in 2018 would rank among the costliest U.S. hurricanes. The full extent of the storm's effects remains unclear due to a dearth of conclusive reports from rural areas of Cuba. The unprecedented availability of meteorological data during the hurricane marked a turning point in the United States Weather Bureau's ability to forecast tropical cyclones.

The 1929 Bahamas hurricane was a high-end Category 4 tropical cyclone whose intensity and slow forward speed led to catastrophic damage in the Bahamas in September 1929, particularly on Andros and New Providence islands. Its erratic path and a lack of nearby weather observations made the hurricane difficult to locate and forecast. The storm later made two landfalls in Florida, killing eleven but causing comparatively light damage. Moisture from the storm led to extensive flooding over the Southeastern United States, particularly along the Savannah River. Across its path from the Bahamas to the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River, the hurricane killed 155 people.

The 1932 Bahamas hurricane, also known as the Great Abaco hurricane of 1932, was a large and powerful Category 5 hurricane that struck the Bahamas at peak intensity. The fourth tropical storm and third hurricane in the 1932 Atlantic hurricane season, it was also one of two Category 5 hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean that year, the other being the 1932 Cuba hurricane. The 1932 Bahamas hurricane originated north of the Virgin Islands, became a strong hurricane, and passed over the northern Bahamas before recurving. The storm never made landfall on the continental United States, but its effects were felt in the northeast part of the country and in the Bahamas, especially on the Abaco Islands, where damage was very great. To date, it is one of four Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes to make landfall in the Bahamas at that intensity, the others having occurred in 1933, 1992, and 2019.

The Tampa Bay hurricane of 1921 was a destructive and deadly major hurricane which made landfall in the Tampa Bay area of Florida in late October 1921. The eleventh tropical cyclone, sixth tropical storm, and fifth hurricane of the season, the storm developed from a trough in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on October 20. Initially a tropical storm, the system moved northwestward and intensified into a hurricane on October 22 and a major hurricane by October 23. Later that day, the hurricane peaked as a Category 4 on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h). After entering the Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane gradually curved northeastward and weakened to a Category 3 before making landfall near Tarpon Springs, Florida, late on October 25. It was the first major hurricane to make landfall in the Tampa Bay area since the hurricane of 1848 and the last to date.

The effects of Hurricane Wilma in Florida resulted in the storm becoming one of the costliest tropical cyclones in Florida history. Wilma developed in the Caribbean Sea just southwest of Jamaica on October 15 from a large area of disturbed weather. After reaching tropical storm intensity on October 17 and then hurricane status on October 18, the system explosively deepened, peaking as the strongest tropical cyclone ever recorded in the Atlantic basin. Wilma then slowly weakened while trekking to the northwest and fell to Category 4 intensity by the time it struck the Yucatán Peninsula on October 22. Thereafter, a strong cold front swept the storm northeastward into Florida on October 24, with landfall occurring near Cape Romano as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h). Wilma continued rapidly northeastward into the Atlantic Ocean and became extratropical on October 26.

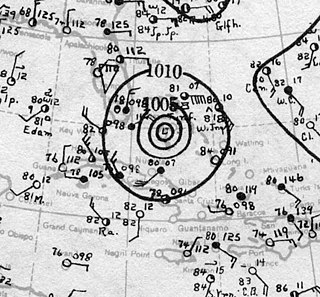

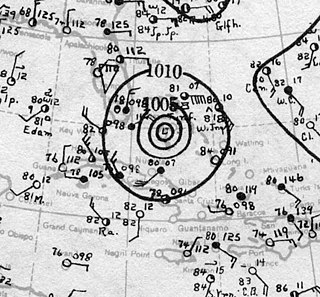

Hurricane Fox was a powerful and destructive tropical cyclone that crossed central Cuba in October 1952. The seventh named storm, sixth hurricane, and third major hurricane of the 1952 Atlantic hurricane season, it was the strongest and deadliest system of the season. Fox developed northwest of Cartagena, Colombia, in the southern Caribbean Sea. It moved steadily northwest, intensifying to a tropical storm on October 21. The next day, it rapidly strengthened into a hurricane and turned north passing closely to Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands. The cyclone attained peak winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) as it struck Cayo Guano del Este off the coast of Cienfuegos. Fox made landfall on Cuba at maximum intensity, producing peak gusts of 170–180 mph (270–290 km/h). It weakened over land, but it re-strengthened as it turned east over the Bahamas. On October 26, it weakened and took an erratic path, dissipating west-southwest of Bermuda on October 28.

The 1903 Florida hurricane was an Atlantic hurricane that caused extensive wind and flood damage on the Florida peninsula and over the adjourning Southeastern United States in early to mid September 1903. The third tropical cyclone and third hurricane of the season, this storm was first observed near Mayaguana island in the Bahamas early on September 9. Moving northwestward, it became a hurricane the next day and passed near Nassau. The cyclone then turned to the west-northwest on September 11 and passed just north of the Bimini Islands. As it crossed the Bahamas, the cyclone produced hurricane-force winds that caused damage to crops and buildings, but no deaths were reported over the island chain.

The 1949 Florida hurricane, also known as the Delray Beach hurricane, caused significant damage in the southern portions of the state late in the month of August. The second recorded tropical cyclone of the annual hurricane season, the system originated from a tropical wave near the northern Leeward Islands on August 23. Already a tropical storm upon initial observations, the cyclone curved west-northwestward and intensified, becoming a hurricane on August 25. Rapid intensification ensued as the storm approached the central Bahamas early on August 26, with the storm reaching Category 4 hurricane strength later that day and peaking with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) shortly after striking Andros. Late on August 26, the storm made landfall near Lake Worth, Florida, at the same intensity. The cyclone initially weakened quickly after moving inland, falling to Category 1 status early the next day. Shortly thereafter, the system curved northward over the Nature Coast and entered Georgia on August 28, where it weakened to a tropical storm. The storm then accelerated northeastward and became extratropical over New England by August 29. The remnants traversed Atlantic Canada and much of the Atlantic Ocean before dissipating near Ireland on September 1.

Hurricane Andrew was a small, but very powerful and destructive Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that struck the Bahamas, Florida, and Louisiana in August 1992. It is the most destructive hurricane to ever hit Florida in terms of structures damaged or destroyed, and remained the costliest in financial terms until Hurricane Irma surpassed it 25 years later. Andrew was also the strongest landfalling hurricane in the United States in decades and the costliest hurricane to strike anywhere in the country, until it was surpassed by Katrina in 2005. In addition, Andrew is one of only four tropical cyclones to make landfall in the continental United States as a Category 5, alongside the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, 1969's Camille, and 2018's Michael. While the storm also caused major damage in the Bahamas and Louisiana, the greatest impact was felt in South Florida, where the storm made landfall as a Category 5 hurricane, with 1-minute sustained wind speeds as high as 165 mph (266 km/h) and a gust as high as 174 mph (280 km/h). Passing directly through the cities of Cutler Bay and Homestead in Dade County, the hurricane stripped many homes of all but their concrete foundations and caused catastrophic damage. In total, Andrew destroyed more than 63,500 houses, damaged more than 124,000 others, caused $27.3 billion in damage, and left 65 people dead.

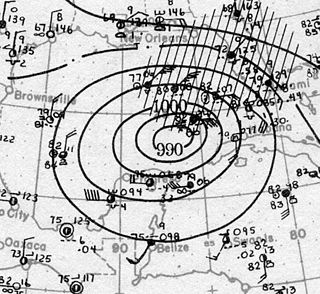

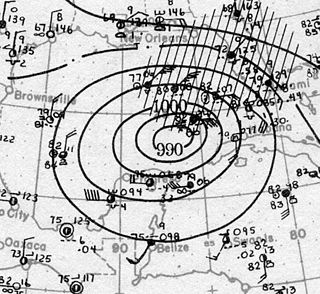

The 1933 Cuba–Brownsville hurricane was one of two storms in the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season to reach Category 5 intensity on the Saffir–Simpson scale. It formed on August 22 off the west coast of Africa, and for much of its duration it maintained a west-northwest track. The system intensified into a tropical storm on August 26 and into a hurricane on August 28. Passing north of the Lesser Antilles, the hurricane rapidly intensified as it approached the Turks and Caicos islands. It reached Category 5 status and its peak winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) on August 31. Subsequently, it weakened before striking northern Cuba on September 1 with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h). In the country, the hurricane left about 100,000 people homeless and killed over 70 people. Damage was heaviest near the storm's path, and the strong winds destroyed houses and left areas without power. Damage was estimated at $11 million.

The 1933 Florida–Mexico hurricane was the first of two Atlantic hurricanes to strike the Treasure Coast region of Florida in the very active 1933 Atlantic hurricane season. It was one of two storms that year to inflict hurricane-force winds over South Texas, causing significant damage there; the other occurred in early September. The fifth tropical cyclone of the year, it formed east of the Lesser Antilles on July 24, rapidly strengthening as it moved west-northwest. As it passed over the islands, it attained hurricane status on July 26, producing heavy rains and killing at least six people. Over the next three days, it moved north of the Caribbean, paralleling the Turks and Caicos Islands and the Bahamas. The storm produced extensive damage and at least one drowning as it crossed the Bahamas. On July 29, the cyclone came under the influence of changing steering currents in the atmosphere, which forced the storm into Florida near Hobe Sound a day later. A minimal hurricane at landfall, it caused negligible wind damage as it crossed Florida, but generated heavy rains along its path, causing locally severe flooding. The storm turned west, weakened to below hurricane status, and later exited the state north of Charlotte Harbor on July 31.