The 1940 Atlantic hurricane season was a generally average period of tropical cyclogenesis in 1940. Though the season had no official bounds, most tropical cyclone activity occurred during August and September. Throughout the year, fourteen tropical cyclones formed, of which nine reached tropical storm intensity; six were hurricanes. None of the hurricanes reached major hurricane intensity. Tropical cyclones that did not approach populated areas or shipping lanes, especially if they were relatively weak and of short duration, may have remained undetected. Because technologies such as satellite monitoring were not available until the 1960s, historical data on tropical cyclones from this period are often not reliable. As a result of a reanalysis project which analyzed the season in 2012, an additional hurricane was added to HURDAT. The year's first tropical storm formed on May 19 off the northern coast of Hispaniola. At the time, this was a rare occurrence, as only four other tropical disturbances were known to have formed prior during this period; since then, reanalysis of previous seasons has concluded that there were more than four tropical cyclones in May before 1940. The season's final system was a tropical disturbance situated in the Greater Antilles, which dissipated on November 8.

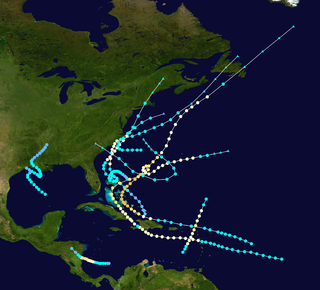

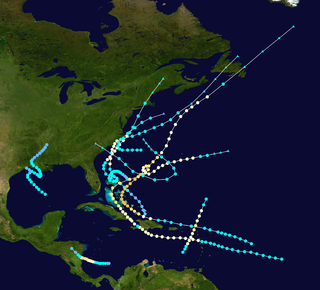

The 1908 Atlantic hurricane season was an active Atlantic hurricane season. Thirteen tropical cyclones formed, of which ten became tropical storms; six became hurricanes, and one of those strengthened into a major hurricane – tropical cyclones that reach at least Category 3 on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale. The season's first system developed on March 6, and the last storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on October 23.

The 1919 Florida Keys hurricane was a massive and damaging tropical cyclone that swept across areas of the northern Caribbean Sea and the United States Gulf Coast in September 1919. Remaining an intense Atlantic hurricane throughout much of its existence, the storm's slow movement and sheer size prolonged and enlarged the scope of the hurricane's effects, making it one of the deadliest hurricanes in United States history. Impacts were largely concentrated around the Florida Keys and South Texas areas, though lesser but nonetheless significant effects were felt in Cuba and other areas of the United States Gulf Coast. The hurricanes peak strength in Dry Tortugas in the lower Florida keys, also made it one of the most powerful Atlantic hurricanes to make landfall in the United States.

The 1898 Atlantic hurricane season marked the beginning of the Weather Bureau operating a network of observation posts across the Caribbean Sea to track tropical cyclones, established primarily due to the onset of the Spanish–American War. A total of eleven tropical storms formed, five of which intensified into a hurricane, according to HURDAT, the National Hurricane Center's official database. Further, one cyclone strengthened into a major hurricane. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated. The first system was initially observed on August 2 near West End in the Bahamas, while the eleventh and final storm dissipated on November 4 over the Mexican state of Veracruz.

The 1891 Atlantic hurricane season began during the summer and ran through the late fall of 1891. The season had ten tropical cyclones. Seven of these became hurricanes; one becoming a major Category 3 hurricane.

Last Island was a barrier island and location of a pleasure resort southwest of New Orleans on the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, United States. Located south of Dulac, Louisiana, between Lake Pelto, Caillou Bay, and the Gulf of Mexico, it was named Last Island because it was the last of a series of barrier islands which stretched westward from the mouth of the Mississippi River, 90 miles to the east.

Hurricane Juan was a large and erratic tropical cyclone that looped twice near the Louisiana coast, causing widespread flooding. It was the tenth named storm of the 1985 Atlantic hurricane season, forming in the central Gulf of Mexico in late October. Juan moved northward after its formation, and was subtropical in nature with its large size. On October 27, the storm became a hurricane, reaching maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). Due to the influence of an upper-level low, Juan looped just off southern Louisiana before making landfall near Morgan City on October 29. Weakening to tropical storm status over land, Juan turned back to the southeast over open waters, crossing the Mississippi River Delta. After turning to the northeast, the storm made its final landfall just west of Pensacola, Florida, late on October 31. Juan continued quickly to the north and was absorbed by an approaching cold front, although its moisture contributed to a deadly flood event in the Mid-Atlantic states.

The Chenière Caminada hurricane, also known as the Great October Storm, was a powerful hurricane that devastated the island of Cheniere Caminada, Louisiana in early October 1893. It was one of three deadly hurricanes during the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season; the storm killed an estimated 2,000 people, mostly from storm surge. The high death toll ranks the hurricane as the deadliest hurricane in Louisiana history and the third deadliest hurricane in the continental U.S., behind only the 1900 Galveston hurricane and the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane.

Hurricane Danny was the only hurricane to make landfall in the United States during the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season, and the second hurricane and fourth tropical storm of the season. The system became the earliest-formed fifth tropical or subtropical storm of the Atlantic season in history when it attained tropical storm strength on July 17, and held that record until the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season when Tropical Storm Emily broke that record by several days. Like the previous four tropical or subtropical cyclones of the season, Danny had a non-tropical origin, after a trough spawned convection that entered the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Danny was guided northeast through the Gulf of Mexico by two high pressure areas, a rare occurrence in the middle of July. After making landfall on the Gulf Coast, Danny tracked across the southeastern United States and ultimately affected parts of New England with rain and wind.

The New Orleans Hurricane of 1915 was an intense Category 4 hurricane that made landfall near Grand Isle, Louisiana, and the most intense tropical cyclone during the 1915 Atlantic hurricane season. The storm formed in late September when it moved westward and peaked in intensity of 145 mph (233 km/h) to weaken slightly by time of landfall on September 29 with recorded wind speeds of 126 mph (203 km/h) as a strong category 3 Hurricane. The hurricane killed 275 people and caused $13 million in damage.

The 1882 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the summer and early fall of 1882. This is the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. In the 1882 Atlantic season there were two tropical storms, two Category 1 hurricanes, and two major hurricanes. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated. Of the known 1882 cyclones, Hurricane One and Hurricane Five were both first documented in 1996 by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz, while Tropical Storm Three was first recognised in 1997. Partagas and Diaz also proposed large changes to the known track of Hurricane Two while further re-analysis, in 2000, led to the peak strengths of both Hurricane Two and Hurricane Six being increased. In 2011 the third storm of the year was downgraded from a hurricane to a tropical storm.

The 1854 Atlantic hurricane season featured five known tropical cyclones, three of which made landfall in the United States. At one time, another was believed to have existed near Galveston, Texas in September, but HURDAT – the official Atlantic hurricane database – now excludes this system. The first system, Hurricane One, was initially observed on June 25. The final storm, Hurricane Five, was last observed on October 22. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. No tropical cyclones during this season existed simultaneously. One tropical cyclone has a single known point in its track due to a sparsity of data.

The 1871 Atlantic hurricane season lasted from mid-summer to late-fall. Records show that 1871 featured two tropical storms, four hurricanes and two major hurricanes. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. According to a study in 2004, an undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 is possible. A later study in 2008 estimated that eight or more storms may have been missed prior to 1878.

The 1867 Atlantic hurricane season lasted from mid-summer to late-fall. A total of nine known tropical systems developed during the season, with the earliest forming on June 21, and the last dissipating on October 31. On two occasions during the season, two tropical cyclones simultaneously existed with one another; the first time on August 2, and the second on October 9. Records show that 1867 featured two tropical storms, six hurricanes and one major hurricane. However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated. Of the known 1867 cyclones Hurricanes Three, Four and Six plus Tropical Cyclones Five and Eight were first documented in 1995 by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz. Hurricane One was first identified in 2003 by Cary Mock.

The 1860 Atlantic hurricane season featured three severe hurricanes that struck Louisiana and the Gulf Coast of the United States within a period of seven weeks. The season effectively began on August 8 with the formation of a tropical cyclone in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, and produced seven known tropical storms and hurricanes until the dissipation of the last known system on October 24. Six of the seven storms were strong enough to be considered hurricanes on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale, of which four attained Category 2 status and one attained Category 3 major hurricane strength. The first hurricane was the strongest in both winds and pressure, with peak winds of 125 miles per hour (201 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 950 millibars (28 inHg). Until contemporary reanalysis discovered four previously unknown tropical cyclones that did not affect land, only three hurricanes were known to have existed; all three made landfall in Louisiana, causing severe damage.

The 1863 Atlantic hurricane season featured five landfalling tropical cyclones. In the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 has been estimated. There were seven recorded hurricanes and no major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale. Of the known 1863 cyclones, seven were first documented in 1995 by José Fernández-Partagás and Henry Diaz, while the ninth tropical storm was first documented in 2003. These changes were largely adopted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic hurricane reanalysis in their updates to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT), with some adjustments.

The effects of Hurricane Isaac in Louisiana were more severe than anywhere in the storm's path, and included $611.8615 million in damages and five total deaths. Forming from a tropical wave in the central Atlantic, Isaac traversed across many of the Lesser and Greater Antilles, before reaching peak intensity with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) on August 28, 2012 while in the Gulf of Mexico. Nearing the coast of Louisiana, the Category 1 hurricane slowly moved towards the west, making two landfalls in the state with little change of intensity prior to moving inland for a final time. The hurricane weakened and later dissipated on September 1 while over Missouri. Before landfall, Governor Bobby Jindal declared a state of emergency to the state, as well as ordering the mandatory evacuation of 60,000 residents in low-lying areas of Louisiana along the Tangipahoa River in Tangipahoa Parish.

The 1856 Atlantic hurricane season featured six tropical cyclones, five of which made landfall. The first system, Hurricane One, was first observed in the Gulf of Mexico on August 9. The final storm, Hurricane Six, was last observed on September 22. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. Only two tropical cyclones during the season existed simultaneously. One of the cyclones has only a single known point in its track due to a sparsity of data. Operationally, another tropical cyclone was believed to have existed in the Wilmington, North Carolina area in September, but HURDAT – the official Atlantic hurricane database – excludes this system. Another tropical cyclone that existed over the Northeastern United States in mid-August was later added to HURDAT.

The 1875 Indianola hurricane brought a devastating and deadly storm surge to the coast of Texas. The third known system of the 1875 Atlantic hurricane season, the storm was first considered a tropical cyclone while located east of the Lesser Antilles on September 8. After passing through the Windward Islands and entering the Caribbean Sea, the cyclone gradually began to move more northwestward and brushed the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti late on September 12. On the following day, the storm made a few landfalls on the southern coast of Cuba before moving inland over Sancti Spíritus Province. The system emerged into the Gulf of Mexico near Havana and briefly weakened to a tropical storm. Thereafter, the storm slowly re-intensified and gradually turned westward. On September 16, the hurricane peaked as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). Later that day, the hurricane made landfall near Indianola, Texas. The storm quickly weakened and turned northeastward, before dissipating over Mississippi on September 18.