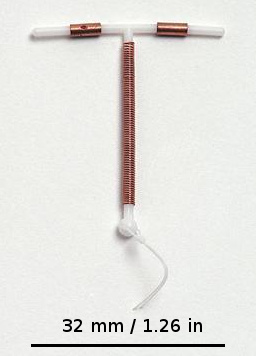

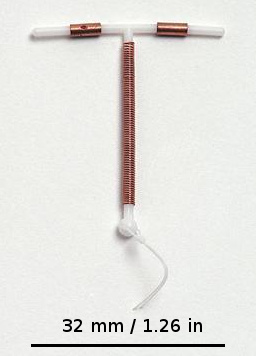

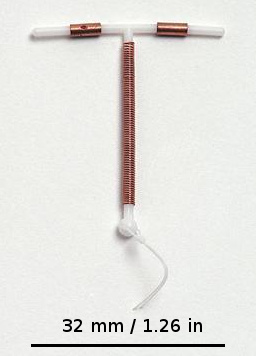

A copper intrauterine device (IUD), also known as an intrauterine coil or copper coil or non-hormonal IUD, is a type of intrauterine device which contains copper. It is used for birth control and emergency contraception within five days of unprotected sex. It is one of the most effective forms of birth control with a one-year failure rate around 0.7%. The device is placed in the uterus and lasts up to twelve years. It may be used by women of all ages regardless of whether or not they have had children. Following removal, fertility quickly returns.

Emergency contraception (EC) is a birth control measure, used after sexual intercourse to prevent pregnancy.

Tubal ligation is a surgical procedure for female sterilization in which the fallopian tubes are permanently blocked, clipped or removed. This prevents the fertilization of eggs by sperm and thus the implantation of a fertilized egg. Tubal ligation is considered a permanent method of sterilization and birth control.

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marital situation, career or work considerations, financial situations. If sexually active, family planning may involve the use of contraception and other techniques to control the timing of reproduction.

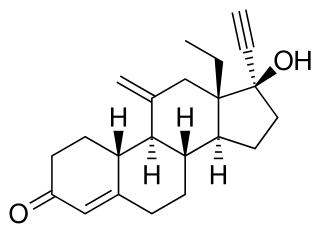

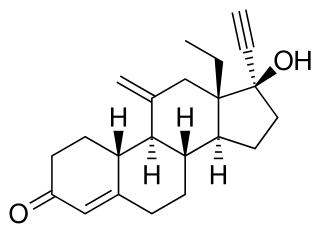

Levonorgestrel is a hormonal medication which is used in a number of birth control methods. It is combined with an estrogen to make combination birth control pills. As an emergency birth control, sold under the brand names Plan B One-Step and Julie, among others, it is useful within 72 hours of unprotected sex. The more time that has passed since sex, the less effective the medication becomes, and it does not work after pregnancy (implantation) has occurred. Levonorgestrel works by preventing ovulation or fertilization from occurring. It decreases the chances of pregnancy by 57–93%. In an intrauterine device (IUD), such as Mirena among others, it is effective for the long-term prevention of pregnancy. A levonorgestrel-releasing implant is also available in some countries.

A hormonal intrauterine device (IUD), also known as an intrauterine system (IUS) with progestogen and sold under the brand name Mirena among others, is an intrauterine device that releases a progestogenic hormonal agent such as levonorgestrel into the uterus. It is used for birth control, heavy menstrual periods, and to prevent excessive build of the lining of the uterus in those on estrogen replacement therapy. It is one of the most effective forms of birth control with a one-year failure rate around 0.2%. The device is placed in the uterus and lasts three to eight years. Fertility often returns quickly following removal.

Hormonal contraception refers to birth control methods that act on the endocrine system. Almost all methods are composed of steroid hormones, although in India one selective estrogen receptor modulator is marketed as a contraceptive. The original hormonal method—the combined oral contraceptive pill—was first marketed as a contraceptive in 1960. In the ensuing decades, many other delivery methods have been developed, although the oral and injectable methods are by far the most popular. Hormonal contraception is highly effective: when taken on the prescribed schedule, users of steroid hormone methods experience pregnancy rates of less than 1% per year. Perfect-use pregnancy rates for most hormonal contraceptives are usually around the 0.3% rate or less. Currently available methods can only be used by women; the development of a male hormonal contraceptive is an active research area.

Etonogestrel is a medication which is used as a means of birth control for women. It is available as an implant placed under the skin of the upper arm under the brand names Nexplanon and Implanon. It is a progestin that is also used in combination with ethinylestradiol, an estrogen, as a vaginal ring under the brand names NuvaRing and Circlet. Etonogestrel is effective as a means of birth control and lasts at least three or four years with some data showing effectiveness for five years. Following removal, fertility quickly returns.

Controversy over the beginning of pregnancy occurs in different contexts, particularly as it is discussed within the debate of abortion in the United States. Because an abortion is defined as ending an established pregnancy, rather than as destroying a fertilized egg, depending on when pregnancy is considered to begin, some methods of birth control as well as some methods of infertility treatment might be classified as causing abortions.

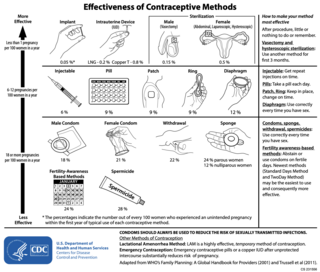

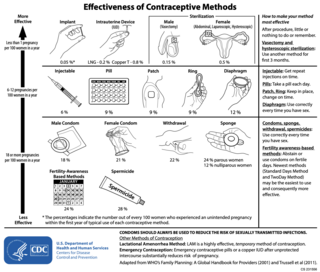

There are many methods of birth control that vary in requirements, side effects, and effectiveness. As the technology, education, and awareness about contraception has evolved, new contraception methods have been theorized and put in application. Although no method of birth control is ideal for every user, some methods remain more effective, affordable or intrusive than others. Outlined here are the different types of barrier methods, hormonal methods, various methods including spermicides, emergency contraceptives, and surgical methods and a comparison between them.

Contraceptive security is an individual's ability to reliably choose, obtain, and use quality contraceptives for family planning and the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. The term refers primarily to efforts undertaken in low and middle-income countries to ensure contraceptive availability as an integral part of family planning programs. Even though there is a consistent increase in the use of contraceptives in low, middle, and high-income countries, the actual contraceptive use varies in different regions of the world. The World Health Organization recognizes the importance of contraception and describes all choices regarding family planning as human rights. Subsidized products, particularly condoms and oral contraceptives, may be provided to increase accessibility for low-income people. Measures taken to provide contraceptive security may include strengthening contraceptive supply chains, forming contraceptive security committees, product quality assurance, promoting supportive policy environments, and examining financing options.

A contraceptive implant is an implantable medical device used for the purpose of birth control. The implant may depend on the timed release of hormones to hinder ovulation or sperm development, the ability of copper to act as a natural spermicide within the uterus, or it may work using a non-hormonal, physical blocking mechanism. As with other contraceptives, a contraceptive implant is designed to prevent pregnancy, but it does not protect against sexually transmitted infections.

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unintended pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only became available in the 20th century. Planning, making available, and using human birth control is called family planning. Some cultures limit or discourage access to birth control because they consider it to be morally, religiously, or politically undesirable.

Sex after pregnancy is often delayed for several weeks or months, and may be difficult and painful for women. Painful intercourse is the most common sexual activity-related complication after childbirth. Since there are no guidelines on resuming sexual intercourse after childbirth, the postpartum patients are generally advised to resume sex when they feel comfortable to do so. Injury to the perineum or surgical cuts (episiotomy) to the vagina during childbirth can cause sexual dysfunction. Sexual activity in the postpartum period other than sexual intercourse is possible sooner, but some women experience a prolonged loss of sexual desire after giving birth, which may be associated with postnatal depression. Common issues that may last more than a year after birth are greater desire by the man than the woman, and a worsening of the woman's body image.

An intrauterine device (IUD), also known as intrauterine contraceptive device or coil, is a small, often T-shaped birth control device that is inserted into the uterus to prevent pregnancy. IUDs are one form of long-acting reversible birth control (LARC). One study found that female family planning providers choose LARC methods more often (41.7%) than the general public (12.1%). Among birth control methods, IUDs, along with other contraceptive implants, result in the greatest satisfaction among users.

Reproductive coercion is a collection of behaviors that interfere with decision-making related to reproductive health. These behaviors are meant to maintain power and control related to reproductive health by a current, former, or hopeful intimate or romantic partner, but they can also be perpetrated by parents or in-laws. Coercive behaviors infringe on individuals' reproductive rights and reduce their reproductive autonomy.

Women's reproductive health in the United States refers to the set of physical, mental, and social issues related to the health of women in the United States. It includes the rights of women in the United States to adequate sexual health, available contraception methods, and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases. The prevalence of women's health issues in American culture is inspired by second-wave feminism in the United States. As a result of this movement, women of the United States began to question the largely male-dominated health care system and demanded a right to information on issues regarding their physiology and anatomy. The U.S. government has made significant strides to propose solutions, like creating the Women's Health Initiative through the Office of Research on Women's Health in 1991. However, many issues still exist related to the accessibility of reproductive healthcare as well as the stigma and controversy attached to sexual health, contraception, and sexually transmitted diseases.

Contraceptive use is important to slow population growth as well as a reduction in neonatal mortality, maternal mortality and adverse perinatal outcomes. In Bangladesh, an estimated 60% of married women currently use a method of contraception.

Combined hormonal contraception (CHC), or combined birth control, is a form of hormonal contraception which combines both an estrogen and a progestogen in varying formulations.

Menstrual suppression refers to the practice of using hormonal management to stop or reduce menstrual bleeding. In contrast to surgical options for this purpose, such as hysterectomy or endometrial ablation, hormonal methods to manipulate menstruation are reversible.