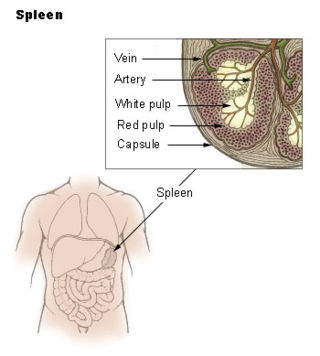

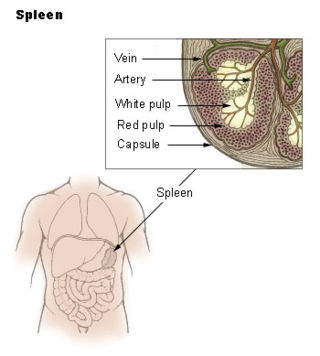

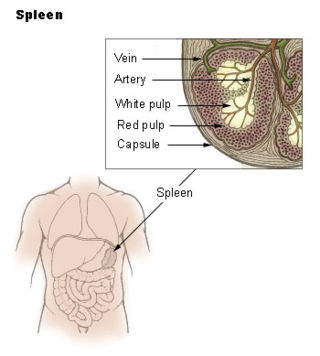

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes from Ancient Greek σπλήν (splḗn).

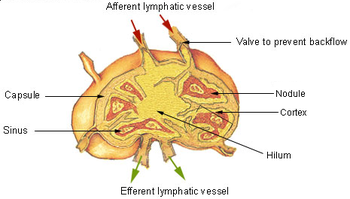

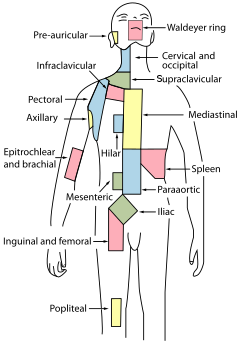

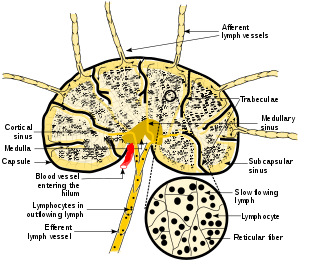

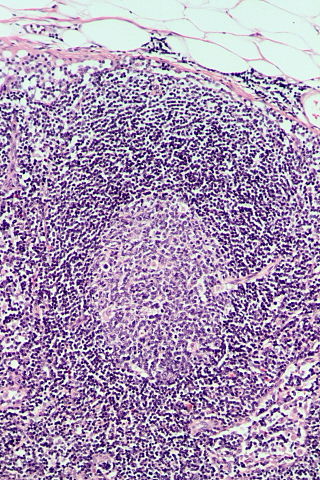

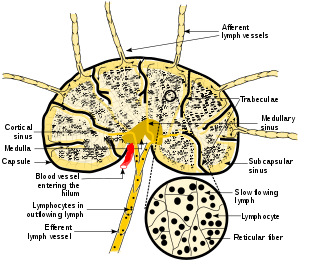

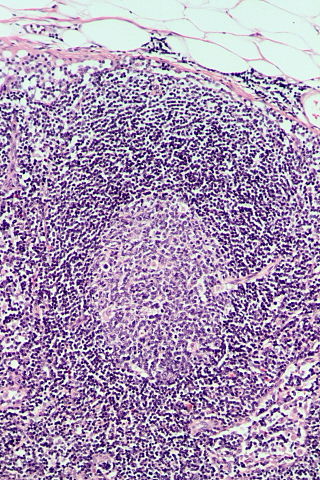

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that include B and T cells. Lymph nodes are important for the proper functioning of the immune system, acting as filters for foreign particles including cancer cells, but have no detoxification function.

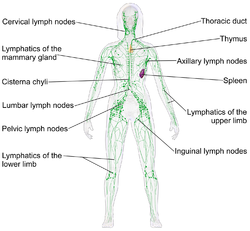

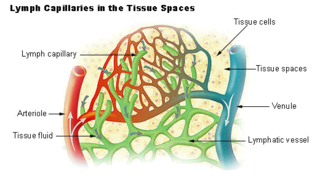

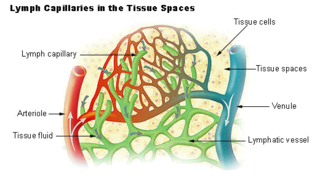

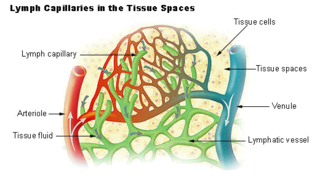

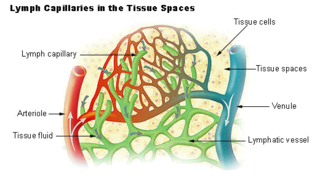

Lymph is the fluid that flows through the lymphatic system, a system composed of lymph vessels (channels) and intervening lymph nodes whose function, like the venous system, is to return fluid from the tissues to be recirculated. At the origin of the fluid-return process, interstitial fluid—the fluid between the cells in all body tissues—enters the lymph capillaries. This lymphatic fluid is then transported via progressively larger lymphatic vessels through lymph nodes, where substances are removed by tissue lymphocytes and circulating lymphocytes are added to the fluid, before emptying ultimately into the right or the left subclavian vein, where it mixes with central venous blood.

The lymphatic vessels are thin-walled vessels (tubes), structured like blood vessels, that carry lymph. As part of the lymphatic system, lymph vessels are complementary to the cardiovascular system. Lymph vessels are lined by endothelial cells, and have a thin layer of smooth muscle, and adventitia that binds the lymph vessels to the surrounding tissue. Lymph vessels are devoted to the propulsion of the lymph from the lymph capillaries, which are mainly concerned with the absorption of interstitial fluid from the tissues. Lymph capillaries are slightly bigger than their counterpart capillaries of the vascular system. Lymph vessels that carry lymph to a lymph node are called afferent lymph vessels, and those that carry it from a lymph node are called efferent lymph vessels, from where the lymph may travel to another lymph node, may be returned to a vein, or may travel to a larger lymph duct. Lymph ducts drain the lymph into one of the subclavian veins and thus return it to general circulation.

The interstitium is a contiguous fluid-filled space existing between a structural barrier, such as a cell membrane or the skin, and internal structures, such as organs, including muscles and the circulatory system. The fluid in this space is called interstitial fluid, comprises water and solutes, and drains into the lymph system. The interstitial compartment is composed of connective and supporting tissues within the body – called the extracellular matrix – that are situated outside the blood and lymphatic vessels and the parenchyma of organs. The role of the interstitium in solute concentration, protein transport and hydrostatic pressure impacts human pathology and physiological responses such as edema, inflammation and shock.

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is a component of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) which works in the immune system to protect the body from invasion in the gut.

The marginal zone is the region at the interface between the non-lymphoid red pulp and the lymphoid white-pulp of the spleen.

Myeloid tissue, in the bone marrow sense of the word myeloid, is tissue of bone marrow, of bone marrow cell lineage, or resembling bone marrow, and myelogenous tissue is any tissue of, or arising from, bone marrow; in these senses the terms are usually used synonymously, as for example with chronic myeloid/myelogenous leukemia.

Kurloff cells were described as mononuclear cells in the peripheral blood and organs of the guinea pig, capybara, paca, agouti and cavie. The Kurloff cell contains a characteristic proteoglycan-containing inclusion body. In the guinea pig, Kurloff cells are more numerous in the adult female than the adult male. A marked increase in the number of circulating Kurloff cells is present in the peripheral blood during pregnancy and after estrogen treatment in male and female animals. A relatively smaller number of cells take place in immature, non-pregnant, and non-estrogen-treated animals. The exact function of Kurloff cells remains unknown, but it has some of the characteristics of both monocytes and lymphocytes. In guinea-pigs, it has been proposed that Kurloff cells mainly involve in the function of the immune system, such as acting as a natural killer cell and preventing damage to the trophoblast by maternal defensive cells. Also, Kurloff cells present antibody-dependent cytotoxic activity in vitro.

White pulp is a histological designation for regions of the spleen, that encompasses approximately 25% of splenic tissue. White pulp consists entirely of lymphoid tissue.

Immune tolerance, also known as immunological tolerance or immunotolerance, refers to the immune system's state of unresponsiveness to substances or tissues that would otherwise trigger an immune response. It arises from prior exposure to a specific antigen and contrasts the immune system's conventional role in eliminating foreign antigens. Depending on the site of induction, tolerance is categorized as either central tolerance, occurring in the thymus and bone marrow, or peripheral tolerance, taking place in other tissues and lymph nodes. Although the mechanisms establishing central and peripheral tolerance differ, their outcomes are analogous, ensuring immune system modulation.

High endothelial venules (HEV) are specialized post-capillary venules characterized by plump endothelial cells as opposed to the usual flatter endothelial cells found in regular venules. HEVs enable lymphocytes circulating in the blood to directly enter a lymph node.

Lymphopoiesis (lĭm'fō-poi-ē'sĭs) is the generation of lymphocytes, one of the five types of white blood cells (WBCs). It is more formally known as lymphoid hematopoiesis.

The tonsils are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil, two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. These organs play an important role in the immune system.

Lymph capillaries or lymphatic capillaries are tiny, thin-walled microvessels located in the spaces between cells which serve to drain and process extracellular fluid. Upon entering the lumen of a lymphatic capillary, the collected fluid is known as lymph. Each lymphatic capillary carries lymph into a lymphatic vessel, which in turn connects to a lymph node, a small bean-shaped gland that filters and monitors the lymphatic fluid for infections. Lymph is ultimately returned to the venous circulation.

Chemokine ligand 21 (CCL21) is a small cytokine belonging to the CC chemokine family. This chemokine is also known as 6Ckine, exodus-2, and secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine (SLC). CCL21 elicits its effects by binding to a cell surface chemokine receptor known as CCR7. The main function of CCL21 is to guide CCR7 expressing leukocytes to the secondary lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes and Peyer´s patches.

Lymphocyte homing receptors are cell adhesion molecules expressed on lymphocyte cell membranes that recognize addressins on target tissues. Lymphocyte homing refers to adhesion of the circulating lymphocytes in blood to specialized endothelial cells within lymphoid organs. These diverse tissue-specific adhesion molecules on lymphocytes and on endothelial cells contribute to the development of specialized immune responses.

C-C chemokine receptor type 7 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CCR7 gene. Two ligands have been identified for this receptor: the chemokines ligand 19 (CCL19/ELC) and ligand 21 (CCL21). The ligands have similar affinity for the receptor, though CCL19 has been shown to induce internalisation of CCR7 and desensitisation of the cell to CCL19/CCL21 signals. CCR7 is a transmembrane protein with 7 transmembrane domains, which is coupled with heterotrimeric G proteins, which transduce the signal downstream through various signalling cascades. The main function of the receptor is to guide immune cells to immune organs by detecting specific chemokines, which these tissues secrete.

Lymph node stromal cells are essential to the structure and function of the lymph node whose functions include: creating an internal tissue scaffold for the support of hematopoietic cells; the release of small molecule chemical messengers that facilitate interactions between hematopoietic cells; the facilitation of the migration of hematopoietic cells; the presentation of antigens to immune cells at the initiation of the adaptive immune system; and the homeostasis of lymphocyte numbers. Stromal cells originate from multipotent mesenchymal stem cells.

Follicular hyperplasia (FH) is a type of lymphoid hyperplasia and is classified as a lymphadenopathy, which means a disease of the lymph nodes. It is caused by a stimulation of the B cell compartment and by abnormal cell growth of secondary follicles. This typically occurs in the cortex without disrupting the lymph node capsule. The follicles are pathologically polymorphous, are often contrasting and varying in size and shape. Follicular hyperplasia is distinguished from follicular lymphoma in its polyclonality and lack of bcl-2 protein expression, whereas follicular lymphoma is monoclonal, and expresses bcl-2.