In chemistry, mechanically interlocked molecular architectures (MIMAs) are molecules that are connected as a consequence of their topology. This connection of molecules is analogous to keys on a keychain loop. The keys are not directly connected to the keychain loop but they cannot be separated without breaking the loop. On the molecular level, the interlocked molecules cannot be separated without the breaking of the covalent bonds that comprise the conjoined molecules; this is referred to as a mechanical bond. Examples of mechanically interlocked molecular architectures include catenanes, rotaxanes, molecular knots, and molecular Borromean rings. Work in this area was recognized with the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Bernard L. Feringa, Jean-Pierre Sauvage, and J. Fraser Stoddart. [1] [2] [3] [4]

The synthesis of such entangled architectures has been made efficient by combining supramolecular chemistry with traditional covalent synthesis, however mechanically interlocked molecular architectures have properties that differ from both "supramolecular assemblies" and "covalently bonded molecules". The terminology "mechanical bond" has been coined to describe the connection between the components of mechanically interlocked molecular architectures. Although research into mechanically interlocked molecular architectures is primarily focused on artificial compounds, many examples have been found in biological systems including: cystine knots, cyclotides or lasso-peptides such as microcin J25 which are proteins, and a variety of peptides.

Residual topology [5] is a descriptive stereochemical term to classify a number of intertwined and interlocked molecules, which cannot be disentangled in an experiment without breaking of covalent bonds, while the strict rules of mathematical topology allow such a disentanglement. Examples of such molecules are rotaxanes, catenanes with covalently linked rings (so-called pretzelanes), and open knots (pseudoknots) which are abundant in proteins.

The term "residual topology" was suggested on account of a striking similarity of these compounds to the well-established topologically nontrivial species, such as catenanes and knotanes (molecular knots). The idea of residual topological isomerism introduces a handy scheme of modifying the molecular graphs and generalizes former efforts of systemization of mechanically bound and bridged molecules.

Experimentally the first examples of mechanically interlocked molecular architectures appeared in the 1960s with catenanes being synthesized by Wasserman and Schill and rotaxanes by Harrison and Harrison. The chemistry of MIMAs came of age when Sauvage pioneered their synthesis using templating methods. [6] In the early 1990s the usefulness and even the existence of MIMAs were challenged. The latter concern was addressed by X ray crystallographer and structural chemist David Williams. Two postdoctoral researchers who took on the challenge of producing [5]catenane (olympiadane) pushed the boundaries of the complexity of MIMAs that could be synthesized their success was confirmed in 1996 by a solid‐state structure analysis conducted by David Williams. [7]

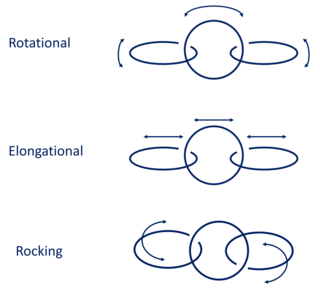

The introduction of a mechanical bond alters the chemistry of the sub components of rotaxanes and catenanes. Steric hindrance of reactive functionalities is increased and the strength of non-covalent interactions between the components are altered. [8]

The strength of non-covalent interactions in a mechanically interlocked molecular architecture increases as compared to the non-mechanically bonded analogues. This increased strength is demonstrated by the necessity of harsher conditions to remove a metal template ion from catenanes as opposed to their non-mechanically bonded analogues. This effect is referred to as the "catenand effect". [9] [10] The augmented non-covalent interactions in interlocked systems compared to non-interlocked systems has found utility in the strong and selective binding of a range of charged species, enabling the development of interlocked systems for the extraction of a range of salts. [11] This increase in strength of non-covalent interactions is attributed to the loss of degrees of freedom upon the formation of a mechanical bond. The increase in strength of non-covalent interactions is more pronounced on smaller interlocked systems, where more degrees of freedom are lost, as compared to larger mechanically interlocked systems where the change in degrees of freedom is lower. Therefore, if the ring in a rotaxane is made smaller the strength of non-covalent interactions increases, the same effect is observed if the thread is made smaller as well. [12]

The mechanical bond can reduce the kinetic reactivity of the products, this is ascribed to the increased steric hindrance. Because of this effect hydrogenation of an alkene on the thread of a rotaxane is significantly slower as compared to the equivalent non interlocked thread. [13] This effect has allowed for the isolation of otherwise reactive intermediates.

The ability to alter reactivity without altering covalent structure has led to MIMAs being investigated for a number of technological applications.

The ability for a mechanical bond to reduce reactivity and hence prevent unwanted reactions has been exploited in a number of areas. One of the earliest applications was in the protection of organic dyes from environmental degradation.

An intermolecular force (IMF) is the force that mediates interaction between molecules, including the electromagnetic forces of attraction or repulsion which act between atoms and other types of neighbouring particles, e.g. atoms or ions. Intermolecular forces are weak relative to intramolecular forces – the forces which hold a molecule together. For example, the covalent bond, involving sharing electron pairs between atoms, is much stronger than the forces present between neighboring molecules. Both sets of forces are essential parts of force fields frequently used in molecular mechanics.

A rotaxane is a mechanically interlocked molecular architecture consisting of a dumbbell-shaped molecule which is threaded through a macrocycle. The two components of a rotaxane are kinetically trapped since the ends of the dumbbell are larger than the internal diameter of the ring and prevent dissociation (unthreading) of the components since this would require significant distortion of the covalent bonds.

Supramolecular chemistry refers to the branch of chemistry concerning chemical systems composed of a discrete number of molecules. The strength of the forces responsible for spatial organization of the system range from weak intermolecular forces, electrostatic charge, or hydrogen bonding to strong covalent bonding, provided that the electronic coupling strength remains small relative to the energy parameters of the component. While traditional chemistry concentrates on the covalent bond, supramolecular chemistry examines the weaker and reversible non-covalent interactions between molecules. These forces include hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, pi–pi interactions and electrostatic effects.

A polycatenane is a chemical substance that, like polymers, is chemically constituted by a large number of units. These units are made up of concatenated rings into a chain-like structure.

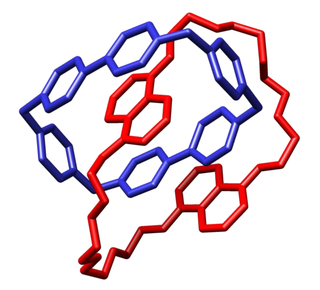

In macromolecular chemistry, a catenane is a mechanically interlocked molecular architecture consisting of two or more interlocked macrocycles, i.e. a molecule containing two or more intertwined rings. The interlocked rings cannot be separated without breaking the covalent bonds of the macrocycles. They are conceptually related to other mechanically interlocked molecular architectures, such as rotaxanes, molecular knots or molecular Borromean rings. Recently the terminology "mechanical bond" has been coined that describes the connection between the macrocycles of a catenane. Catenanes have been synthesised in two different ways: statistical synthesis and template-directed synthesis.

Topoisomers or topological isomers are molecules with the same chemical formula and stereochemical bond connectivities but different topologies. Examples of molecules for which there exist topoisomers include DNA, which can form knots, and catenanes. Each topoisomer of a given DNA molecule possesses a different linking number associated with it. DNA topoisomers can be interchanged by enzymes called topoisomerases. Using a topoisomerase along with an intercalator, topoisomers with different linking number may be separated on an agarose gel via gel electrophoresis.

Interlock can refer to the following:

In chemistry, a molecular knot is a mechanically interlocked molecular architecture that is analogous to a macroscopic knot. Naturally-forming molecular knots are found in organic molecules like DNA, RNA, and proteins. It is not certain that naturally occurring knots are evolutionarily advantageous to nucleic acids or proteins, though knotting is thought to play a role in the structure, stability, and function of knotted biological molecules. The mechanism by which knots naturally form in molecules, and the mechanism by which a molecule is stabilized or improved by knotting, is ambiguous. The study of molecular knots involves the formation and applications of both naturally occurring and chemically synthesized molecular knots. Applying chemical topology and knot theory to molecular knots allows biologists to better understand the structures and synthesis of knotted organic molecules.

In supramolecular chemistry, host–guest chemistry describes complexes that are composed of two or more molecules or ions that are held together in unique structural relationships by forces other than those of full covalent bonds. Host–guest chemistry encompasses the idea of molecular recognition and interactions through non-covalent bonding. Non-covalent bonding is critical in maintaining the 3D structure of large molecules, such as proteins and is involved in many biological processes in which large molecules bind specifically but transiently to one another.

Molecular machines are a class of molecules typically described as an assembly of a discrete number of molecular components intended to produce mechanical movements in response to specific stimuli, mimicking macromolecular devices such as switches and motors. Naturally occurring or biological molecular machines are responsible for vital living processes such as DNA replication and ATP synthesis. Kinesins and ribosomes are examples of molecular machines, and they often take the form of multi-protein complexes. For the last several decades, scientists have attempted, with varying degrees of success, to miniaturize machines found in the macroscopic world. The first example of an artificial molecular machine (AMM) was reported in 1994, featuring a rotaxane with a ring and two different possible binding sites.

In chemistry, molecular Borromean rings are an example of a mechanically-interlocked molecular architecture in which three macrocycles are interlocked in such a way that breaking any macrocycle allows the others to dissociate. They are the smallest examples of Borromean rings. The synthesis of molecular Borromean rings was reported in 2004 by the group of J. Fraser Stoddart. The so-called Borromeate is made up of three interpenetrated macrocycles formed through templated self assembly as complexes of zinc.

Dynamic covalent chemistry (DCvC) is a synthetic strategy employed by chemists to make complex molecular and supramolecular assemblies from discrete molecular building blocks. DCvC has allowed access to complex assemblies such as covalent organic frameworks, molecular knots, polymers, and novel macrocycles. Not to be confused with dynamic combinatorial chemistry, DCvC concerns only covalent bonding interactions. As such, it only encompasses a subset of supramolecular chemistries.

Sir James Fraser Stoddart is a British-American chemist who is Board of Trustees Professor of Chemistry and head of the Stoddart Mechanostereochemistry Group in the Department of Chemistry at Northwestern University in the United States. He works in the area of supramolecular chemistry and nanotechnology. Stoddart has developed highly efficient syntheses of mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures such as molecular Borromean rings, catenanes and rotaxanes utilising molecular recognition and molecular self-assembly processes. He has demonstrated that these topologies can be employed as molecular switches. His group has even applied these structures in the fabrication of nanoelectronic devices and nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS). His efforts have been recognized by numerous awards including the 2007 King Faisal International Prize in Science. He shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry together with Ben Feringa and Jean-Pierre Sauvage in 2016 for the design and synthesis of molecular machines.

Jean-Pierre Sauvage is a French coordination chemist working at Strasbourg University. He graduated from the National School of Chemistry of Strasbourg, in 1967. He has specialized in supramolecular chemistry for which he has been awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Sir J. Fraser Stoddart and Bernard L. Feringa.

Cation–π interaction is a noncovalent molecular interaction between the face of an electron-rich π system (e.g. benzene, ethylene, acetylene) and an adjacent cation (e.g. Li+, Na+). This interaction is an example of noncovalent bonding between a monopole (cation) and a quadrupole (π system). Bonding energies are significant, with solution-phase values falling within the same order of magnitude as hydrogen bonds and salt bridges. Similar to these other non-covalent bonds, cation–π interactions play an important role in nature, particularly in protein structure, molecular recognition and enzyme catalysis. The effect has also been observed and put to use in synthetic systems.

In polymer chemistry and materials science, the term "polymer" refers to large molecules whose structure is composed of multiple repeating units. Supramolecular polymers are a new category of polymers that can potentially be used for material applications beyond the limits of conventional polymers. By definition, supramolecular polymers are polymeric arrays of monomeric units that are connected by reversible and highly directional secondary interactions–that is, non-covalent bonds. These non-covalent interactions include van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding, Coulomb or ionic interactions, π-π stacking, metal coordination, halogen bonding, chalcogen bonding, and host–guest interaction. The direction and strength of the interactions are precisely tuned so that the array of molecules behaves as a polymer in dilute and concentrated solution, as well as in the bulk.

David Alan Leigh FRS FRSE FRSC is a British chemist, Royal Society Research Professor and, since 2014, the Sir Samuel Hall Chair of Chemistry in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Manchester. He was previously the Forbes Chair of Organic Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh (2001–2012) and Professor of Synthetic Chemistry at the University of Warwick (1998–2001).

A molecular switch is a molecule that can be reversibly shifted between two or more stable states. The molecules may be shifted between the states in response to environmental stimuli, such as changes in pH, light, temperature, an electric current, microenvironment, or in the presence of ions and other ligands. In some cases, a combination of stimuli is required. The oldest forms of synthetic molecular switches are pH indicators, which display distinct colors as a function of pH. Currently synthetic molecular switches are of interest in the field of nanotechnology for application in molecular computers or responsive drug delivery systems. Molecular switches are also important in biology because many biological functions are based on it, for instance allosteric regulation and vision. They are also one of the simplest examples of molecular machines.

Cyclobis(paraquat-p-phenylene) belongs to the class of cyclophanes, and consists of aromatic units connected by methylene bridges. It is able to incorporate small guest molecule and has played an important role in host–guest chemistry and supramolecular chemistry.

Polyrotaxane is a type of mechanically interlocked molecule consisting of strings and rings, in which multiple rings are threaded onto a molecular axle and prevented from dethreading by two bulky end groups. As oligomeric or polymeric species of rotaxanes, polyrotaxanes are also capable of converting energy input to molecular movements because the ring motions can be controlled by external stimulus. Polyrotaxanes have attracted much attention for decades, because they can help build functional molecular machines with complicated molecular structure.