A chemical bond is a lasting attraction between atoms or ions that enables the formation of molecules and crystals. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds, or through the sharing of electrons as in covalent bonds. The strength of chemical bonds varies considerably; there are "strong bonds" or "primary bonds" such as covalent, ionic and metallic bonds, and "weak bonds" or "secondary bonds" such as dipole–dipole interactions, the London dispersion force, and hydrogen bonding. Strong chemical bonding arises from the sharing or transfer of electrons between the participating atoms.

Ionic bonding is a type of chemical bonding that involves the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions, or between two atoms with sharply different electronegativities, and is the primary interaction occurring in ionic compounds. It is one of the main types of bonding, along with covalent bonding and metallic bonding. Ions are atoms with an electrostatic charge. Atoms that gain electrons make negatively charged ions. Atoms that lose electrons make positively charged ions. This transfer of electrons is known as electrovalence in contrast to covalence. In the simplest case, the cation is a metal atom and the anion is a nonmetal atom, but these ions can be of a more complex nature, e.g. molecular ions like NH+

4 or SO2−

4. In simpler words, an ionic bond results from the transfer of electrons from a metal to a non-metal in order to obtain a full valence shell for both atoms.

An intermolecular force (IMF) is the force that mediates interaction between molecules, including the electromagnetic forces of attraction or repulsion which act between atoms and other types of neighbouring particles, e.g. atoms or ions. Intermolecular forces are weak relative to intramolecular forces – the forces which hold a molecule together. For example, the covalent bond, involving sharing electron pairs between atoms, is much stronger than the forces present between neighboring molecules. Both sets of forces are essential parts of force fields frequently used in molecular mechanics.

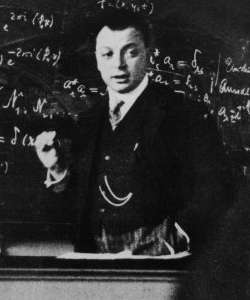

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli exclusion principle states that two or more identical particles with half-integer spins cannot occupy the same quantum state within a quantum system simultaneously. This principle was formulated by Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli in 1925 for electrons, and later extended to all fermions with his spin–statistics theorem of 1940.

Solvation describes the interaction of a solvent with dissolved molecules. Both ionized and uncharged molecules interact strongly with a solvent, and the strength and nature of this interaction influence many properties of the solute, including solubility, reactivity, and color, as well as influencing the properties of the solvent such as its viscosity and density. If the attractive forces between the solvent and solute particles are greater than the attractive forces holding the solute particles together, the solvent particles pull the solute particles apart and surround them. The surrounded solute particles then move away from the solid solute and out into the solution. Ions are surrounded by a concentric shell of solvent. Solvation is the process of reorganizing solvent and solute molecules into solvation complexes and involves bond formation, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces. Solvation of a solute by water is called hydration.

In molecular physics, the van der Waals force is a distance-dependent interaction between atoms or molecules. Unlike ionic or covalent bonds, these attractions do not result from a chemical electronic bond; they are comparatively weak and therefore more susceptible to disturbance. The van der Waals force quickly vanishes at longer distances between interacting molecules.

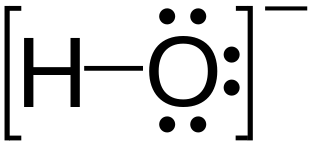

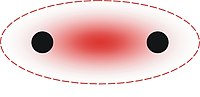

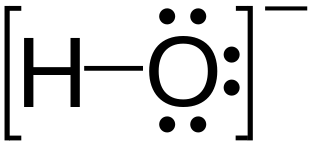

In chemistry, a lone pair refers to a pair of valence electrons that are not shared with another atom in a covalent bond and is sometimes called an unshared pair or non-bonding pair. Lone pairs are found in the outermost electron shell of atoms. They can be identified by using a Lewis structure. Electron pairs are therefore considered lone pairs if two electrons are paired but are not used in chemical bonding. Thus, the number of electrons in lone pairs plus the number of electrons in bonds equals the number of valence electrons around an atom.

Supramolecular chemistry refers to the branch of chemistry concerning chemical systems composed of a discrete number of molecules. The strength of the forces responsible for spatial organization of the system range from weak intermolecular forces, electrostatic charge, or hydrogen bonding to strong covalent bonding, provided that the electronic coupling strength remains small relative to the energy parameters of the component. While traditional chemistry concentrates on the covalent bond, supramolecular chemistry examines the weaker and reversible non-covalent interactions between molecules. These forces include hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, pi–pi interactions and electrostatic effects.

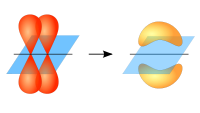

In chemistry, π backbonding, also called π backdonation, is when electrons move from an atomic orbital on one atom to an appropriate symmetry antibonding orbital on a π-acceptor ligand. It is especially common in the organometallic chemistry of transition metals with multi-atomic ligands such as carbon monoxide, ethylene or the nitrosonium cation. Electrons from the metal are used to bond to the ligand, in the process relieving the metal of excess negative charge. Compounds where π backbonding occurs include Ni(CO)4 and Zeise's salt. IUPAC offers the following definition for backbonding:

A description of the bonding of π-conjugated ligands to a transition metal which involves a synergic process with donation of electrons from the filled π-orbital or lone electron pair orbital of the ligand into an empty orbital of the metal (donor–acceptor bond), together with release (back donation) of electrons from an nd orbital of the metal (which is of π-symmetry with respect to the metal–ligand axis) into the empty π*-antibonding orbital of the ligand.

Relativistic quantum chemistry combines relativistic mechanics with quantum chemistry to calculate elemental properties and structure, especially for the heavier elements of the periodic table. A prominent example is an explanation for the color of gold: due to relativistic effects, it is not silvery like most other metals.

In chemistry, a non-covalent interaction differs from a covalent bond in that it does not involve the sharing of electrons, but rather involves more dispersed variations of electromagnetic interactions between molecules or within a molecule. The chemical energy released in the formation of non-covalent interactions is typically on the order of 1–5 kcal/mol. Non-covalent interactions can be classified into different categories, such as electrostatic, π-effects, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects.

In organic chemistry, the anomeric effect or Edward-Lemieux effect is a stereoelectronic effect that describes the tendency of heteroatomic substituents adjacent to a heteroatom within a cyclohexane ring to prefer the axial orientation instead of the less hindered equatorial orientation that would be expected from steric considerations. This effect was originally observed in pyranose rings by J. T. Edward in 1955 when studying carbohydrate chemistry.

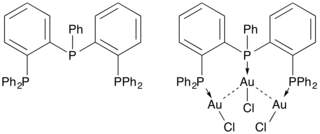

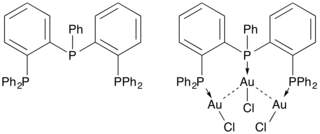

In chemistry, aurophilicity refers to the tendency of gold complexes to aggregate via formation of weak metallophilic interactions.

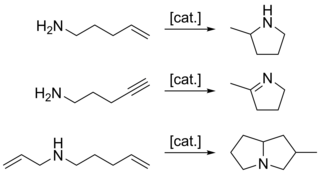

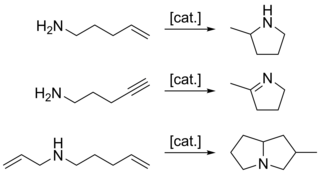

In organic chemistry, hydroamination is the addition of an N−H bond of an amine across a carbon-carbon multiple bond of an alkene, alkyne, diene, or allene. In the ideal case, hydroamination is atom economical and green. Amines are common in fine-chemical, pharmaceutical, and agricultural industries. Hydroamination can be used intramolecularly to create heterocycles or intermolecularly with a separate amine and unsaturated compound. The development of catalysts for hydroamination remains an active area, especially for alkenes. Although practical hydroamination reactions can be effected for dienes and electrophilic alkenes, the term hydroamination often implies reactions metal-catalyzed processes.

A halogen bond occurs when there is evidence of a net attractive interaction between an electrophilic region associated with a halogen atom in a molecular entity and a nucleophilic region in another, or the same, molecular entity. Like a hydrogen bond, the result is not a formal chemical bond, but rather a strong electrostatic attraction. Mathematically, the interaction can be decomposed in two terms: one describing an electrostatic, orbital-mixing charge-transfer and another describing electron-cloud dispersion. Halogen bonds find application in supramolecular chemistry; drug design and biochemistry; crystal engineering and liquid crystals; and organic catalysis.

In chemistry, π-effects or π-interactions are a type of non-covalent interaction that involves π systems. Just like in an electrostatic interaction where a region of negative charge interacts with a positive charge, the electron-rich π system can interact with a metal, an anion, another molecule and even another π system. Non-covalent interactions involving π systems are pivotal to biological events such as protein-ligand recognition.

Organogold chemistry is the study of compounds containing gold–carbon bonds. They are studied in academic research, but have not received widespread use otherwise. The dominant oxidation states for organogold compounds are I with coordination number 2 and a linear molecular geometry and III with CN = 4 and a square planar molecular geometry.

In chemistry, a crossover experiment is a method used to study the mechanism of a chemical reaction. In a crossover experiment, two similar but distinguishable reactants simultaneously undergo a reaction as part of the same reaction mixture. The products formed will either correspond directly to one of the two reactants or will include components of both reactants. The aim of a crossover experiment is to determine whether or not a reaction process involves a stage where the components of each reactant have an opportunity to exchange with each other.

Plumbylenes (or plumbylidenes) are divalent organolead(II) analogues of carbenes, with the general chemical formula, R2Pb, where R denotes a substituent. Plumbylenes possess 6 electrons in their valence shell, and are considered open shell species.

Dispersion stabilized molecules are molecules where the London dispersion force (LDF), a non-covalent attractive force between atoms and molecules, plays a significant role in promoting the molecule's stability. Distinct from steric hindrance, dispersion stabilization has only recently been considered in depth by organic and inorganic chemists after earlier gaining prominence in protein science and supramolecular chemistry. Although usually weaker than covalent bonding and other forms of non-covalent interactions like hydrogen bonding, dispersion forces are known to be a significant if not dominating stabilizing force in certain organic, inorganic, and main group molecules, stabilizing otherwise reactive moieties and exotic bonding.