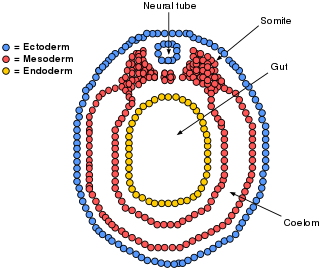

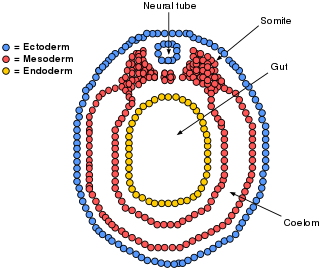

The mesoderm is the middle layer of the three germ layers that develops during gastrulation in the very early development of the embryo of most animals. The outer layer is the ectoderm, and the inner layer is the endoderm.

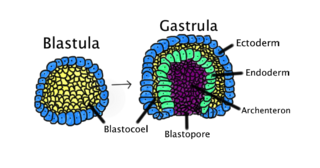

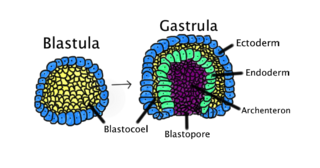

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula, or in mammals the blastocyst is reorganized into a two-layered or three-layered embryo known as the gastrula. Before gastrulation, the embryo is a continuous epithelial sheet of cells; by the end of gastrulation, the embryo has begun differentiation to establish distinct cell lineages, set up the basic axes of the body, and internalized one or more cell types including the prospective gut.

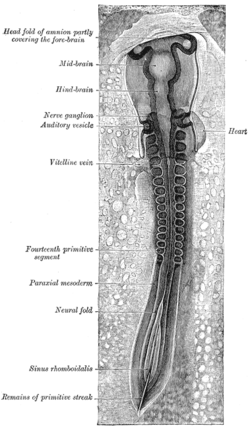

The somites are a set of bilaterally paired blocks of paraxial mesoderm that form in the embryonic stage of somitogenesis, along the head-to-tail axis in segmented animals. In vertebrates, somites subdivide into the dermatomes, myotomes, sclerotomes and syndetomes that give rise to the vertebrae of the vertebral column, rib cage, part of the occipital bone, skeletal muscle, cartilage, tendons, and skin.

A germ layer is a primary layer of cells that forms during embryonic development. The three germ layers in vertebrates are particularly pronounced; however, all eumetazoans produce two or three primary germ layers. Some animals, like cnidarians, produce two germ layers making them diploblastic. Other animals such as bilaterians produce a third layer between these two layers, making them triploblastic. Germ layers eventually give rise to all of an animal's tissues and organs through the process of organogenesis.

Somitogenesis is the process by which somites form. Somites are bilaterally paired blocks of paraxial mesoderm that form along the anterior-posterior axis of the developing embryo in segmented animals. In vertebrates, somites give rise to skeletal muscle, cartilage, tendons, endothelium, and dermis.

Organogenesis is the phase of embryonic development that starts at the end of gastrulation and continues until birth. During organogenesis, the three germ layers formed from gastrulation form the internal organs of the organism.

In developmental biology, animal embryonic development, also known as animal embryogenesis, is the developmental stage of an animal embryo. Embryonic development starts with the fertilization of an egg cell (ovum) by a sperm cell, (spermatozoon). Once fertilized, the ovum becomes a single diploid cell known as a zygote. The zygote undergoes mitotic divisions with no significant growth and cellular differentiation, leading to development of a multicellular embryo after passing through an organizational checkpoint during mid-embryogenesis. In mammals, the term refers chiefly to the early stages of prenatal development, whereas the terms fetus and fetal development describe later stages.

Neural crest cells are a temporary group of cells that arise from the embryonic ectoderm germ layer, and in turn give rise to a diverse cell lineage—including melanocytes, craniofacial cartilage and bone, smooth muscle, peripheral and enteric neurons and glia.

The primitive node is the organizer for gastrulation in most amniote embryos. In birds it is known as Hensen's node, and in amphibians it is known as the Spemann-Mangold organizer. It is induced by the Nieuwkoop center in amphibians, or by the posterior marginal zone in amniotes including birds.

The primitive streak is a structure that forms in the early embryo in amniotes. In amphibians, the equivalent structure is the blastopore. During early embryonic development, the embryonic disc becomes oval shaped, and then pear-shaped with the broad end towards the anterior, and the narrower region projected to the posterior. The primitive streak forms a longitudinal midline structure in the narrower posterior (caudal) region of the developing embryo on its dorsal side. At first formation, the primitive streak extends for half the length of the embryo. In the human embryo, this appears by stage 6, about 17 days.

Intermediate mesoderm or intermediate mesenchyme is a narrow section of the mesoderm located between the paraxial mesoderm and the lateral plate of the developing embryo. The intermediate mesoderm develops into vital parts of the urogenital system.

The lateral plate mesoderm is the mesoderm that is found at the periphery of the embryo. It is to the side of the paraxial mesoderm, and further to the axial mesoderm. The lateral plate mesoderm is separated from the paraxial mesoderm by a narrow region of intermediate mesoderm. The mesoderm is the middle layer of the three germ layers, between the outer ectoderm and inner endoderm.

Bone morphogenetic protein 4 is a protein that in humans is encoded by BMP4 gene. BMP4 is found on chromosome 14q22-q23.

Myogenesis is the formation of skeletal muscular tissue, particularly during embryonic development.

Mesenchyme is a type of loosely organized animal embryonic connective tissue of undifferentiated cells that give rise to most tissues, such as skin, blood or bone. The interactions between mesenchyme and epithelium help to form nearly every organ in the developing embryo.

The limb bud is a structure formed early in vertebrate limb development. As a result of interactions between the ectoderm and underlying mesoderm, formation occurs roughly around the fourth week of development. In the development of the human embryo the upper limb bud appears in the third week and the lower limb bud appears four days later.

Human embryonic development, or human embryogenesis, is the development and formation of the human embryo. It is characterised by the processes of cell division and cellular differentiation of the embryo that occurs during the early stages of development. In biological terms, the development of the human body entails growth from a one-celled zygote to an adult human being. Fertilization occurs when the sperm cell successfully enters and fuses with an egg cell (ovum). The genetic material of the sperm and egg then combine to form the single cell zygote and the germinal stage of development commences. Embryonic development in the human, covers the first eight weeks of development; at the beginning of the ninth week the embryo is termed a fetus. The eight weeks has 23 stages.

Neural crest cells are multipotent cells required for the development of cells, tissues and organ systems. A subpopulation of neural crest cells are the cardiac neural crest complex. This complex refers to the cells found amongst the midotic placode and somite 3 destined to undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transformation and migration to the heart via pharyngeal arches 3, 4 and 6.

The clock and wavefront model is a model used to describe the process of somitogenesis in vertebrates. Somitogenesis is the process by which somites, blocks of mesoderm that give rise to a variety of connective tissues, are formed.

Segmentation is the physical characteristic by which the human body is divided into repeating subunits called segments arranged along a longitudinal axis. In humans, the segmentation characteristic observed in the nervous system is of biological and evolutionary significance. Segmentation is a crucial developmental process involved in the patterning and segregation of groups of cells with different features, generating regional properties for such cell groups and organizing them both within the tissues as well as along the embryonic axis.