Escherichia coli ( ESH-ə-RIK-ee-ə KOH-ly) is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus Escherichia that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms. Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some serotypes such as EPEC, and ETEC are pathogenic and can cause serious food poisoning in their hosts, and are occasionally responsible for food contamination incidents that prompt product recalls. Most strains are part of the normal microbiota of the gut and are harmless or even beneficial to humans (although these strains tend to be less studied than the pathogenic ones). For example, some strains of E. coli benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2 or by preventing the colonization of the intestine by pathogenic bacteria. These mutually beneficial relationships between E. coli and humans are a type of mutualistic biological relationship — where both the humans and the E. coli are benefitting each other. E. coli is expelled into the environment within fecal matter. The bacterium grows massively in fresh fecal matter under aerobic conditions for three days, but its numbers decline slowly afterwards.

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is a serotype of the bacterial species Escherichia coli and is one of the Shiga-like toxin–producing types of E. coli. It is a cause of disease, typically foodborne illness, through consumption of contaminated and raw food, including raw milk and undercooked ground beef. Infection with this type of pathogenic bacteria may lead to hemorrhagic diarrhea, and to kidney failure; these have been reported to cause the deaths of children younger than five years of age, of elderly patients, and of patients whose immune systems are otherwise compromised.

Shigellosis is an infection of the intestines caused by Shigella bacteria. Symptoms generally start one to two days after exposure and include diarrhea, fever, abdominal pain, and feeling the need to pass stools even when the bowels are empty. The diarrhea may be bloody. Symptoms typically last five to seven days and it may take several months before bowel habits return entirely to normal. Complications can include reactive arthritis, sepsis, seizures, and hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Shigella is a genus of bacteria that is Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic, non–spore-forming, nonmotile, rod-shaped, and is genetically closely related to Escherichia. The genus is named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who discovered it in 1897.

Hemolytic–uremic syndrome (HUS) is a group of blood disorders characterized by low red blood cells, acute kidney injury, and low platelets. Initial symptoms typically include bloody diarrhea, fever, vomiting, and weakness. Kidney problems and low platelets then occur as the diarrhea progresses. Children are more commonly affected, but most children recover without permanent damage to their health, although some children may have serious and sometimes life-threatening complications. Adults, especially the elderly, may present a more complicated presentation. Complications may include neurological problems and heart failure.

Shigella dysenteriae is a species of the rod-shaped bacterial genus Shigella. Shigella species can cause shigellosis. Shigellae are Gram-negative, non-spore-forming, facultatively anaerobic, nonmotile bacteria. S. dysenteriae has the ability to invade and replicate in various species of epithelial cells and enterocytes.

Shigella flexneri is a species of Gram-negative bacteria in the genus Shigella that can cause diarrhea in humans. Several different serogroups of Shigella are described; S. flexneri belongs to group B. S. flexneri infections can usually be treated with antibiotics, although some strains have become resistant. Less severe cases are not usually treated because they become more resistant in the future. Shigella are closely related to Escherichia coli, but can be differentiated from E.coli based on pathogenicity, physiology and serology.

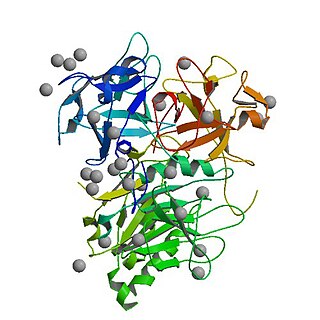

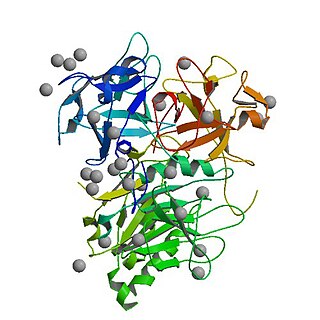

Diphtheria toxin is an exotoxin secreted mainly by Corynebacterium diphtheriae but also by Corynebacterium ulcerans and Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, the pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria. The toxin gene is encoded by a prophage called corynephage β. The toxin causes the disease in humans by gaining entry into the cell cytoplasm and inhibiting protein synthesis.

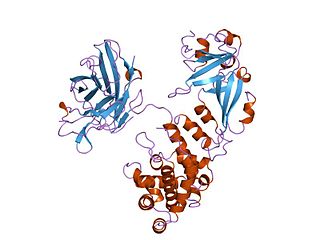

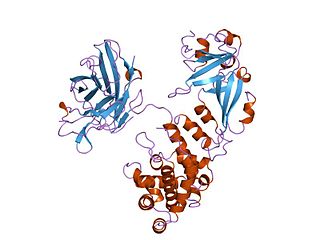

The AB5 toxins are six-component protein complexes secreted by certain pathogenic bacteria known to cause human diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and hemolytic–uremic syndrome. One component is known as the A subunit, and the remaining five components are B subunits. All of these toxins share a similar structure and mechanism for entering targeted host cells. The B subunit is responsible for binding to receptors to open up a pathway for the A subunit to enter the cell. The A subunit is then able to use its catalytic machinery to take over the host cell's regular functions.

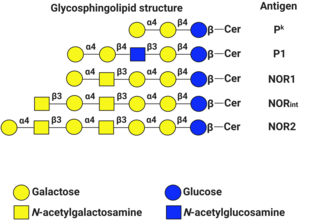

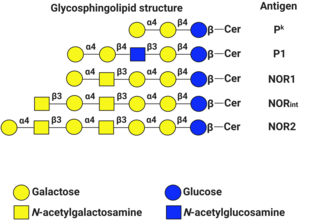

P1PK is a human blood group system based upon the A4GALT gene on chromosome 22. The P antigen was first described by Karl Landsteiner and Philip Levine in 1927. The P1PK blood group system consists of three glycosphingolipid antigens: Pk, P1 and NOR. In addition to glycosphingolipids, terminal Galα1→4Galβ structures are present on complex-type N-glycans. The GLOB antigen is now the member of the separate GLOB (globoside) blood group system.

Microbial toxins are toxins produced by micro-organisms, including bacteria, fungi, protozoa, dinoflagellates, and viruses. Many microbial toxins promote infection and disease by directly damaging host tissues and by disabling the immune system. Endotoxins most commonly refer to the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or lipooligosaccharide (LOS) that are in the outer plasma membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. The botulinum toxin, which is primarily produced by Clostridium botulinum and less frequently by other Clostridium species, is the most toxic substance known in the world. However, microbial toxins also have important uses in medical science and research. Currently, new methods of detecting bacterial toxins are being developed to better isolate and understand these toxins. Potential applications of toxin research include combating microbial virulence, the development of novel anticancer drugs and other medicines, and the use of toxins as tools in neurobiology and cellular biology.

Globotriaosylceramide is a globoside. It is also known as CD77, Gb3, GL3, and ceramide trihexoside. It is one of the few clusters of differentiation that is not a protein.

Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) is a type of pathogenic bacteria whose infection causes a syndrome that is identical to shigellosis, with profuse diarrhea and high fever. EIEC are highly invasive, and they use adhesin proteins to bind to and enter intestinal cells. They produce no toxins, but severely damage the intestinal wall through mechanical cell destruction.

Escherichia coli O104:H4 is an enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strain of the bacterium Escherichia coli, and the cause of the 2011 Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak. The "O" in the serological classification identifies the cell wall lipopolysaccharide antigen, and the "H" identifies the flagella antigen.

Shigatoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) and verotoxigenic E. coli (VTEC) are strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli that produce Shiga toxin. Only a minority of the strains cause illness in humans. The ones that do are collectively known as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) and are major causes of foodborne illness. When infecting the large intestine of humans, they often cause gastroenteritis, enterocolitis, and bloody diarrhea and sometimes cause a severe complication called hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). Cattle is an important natural reservoir for EHEC because the colonised adult ruminants are asymptomatic. This is because they lack vascular expression of the target receptor for Shiga toxins. The group and its subgroups are known by various names. They are distinguished from other strains of intestinal pathogenic E. coli including enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), and diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC).

Cytolethal distending toxins are a class of heterotrimeric toxins produced by certain gram-negative bacteria that display DNase activity. These toxins trigger G2/M cell cycle arrest in specific mammalian cell lines, leading to the enlarged or distended cells for which these toxins are named. Affected cells die by apoptosis.

Escherichia coli is a gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms). Most E. coli strains are harmless, but pathogenic varieties cause serious food poisoning, septic shock, meningitis, or urinary tract infections in humans. Unlike normal flora E. coli, the pathogenic varieties produce toxins and other virulence factors that enable them to reside in parts of the body normally not inhabited by E. coli, and to damage host cells. These pathogenic traits are encoded by virulence genes carried only by the pathogens.

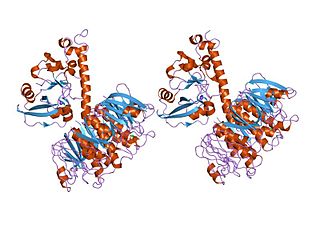

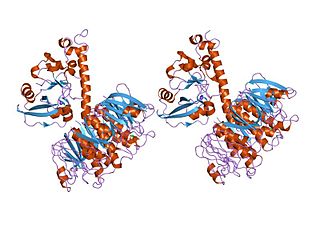

In molecular biology, the heat-labile enterotoxin family includes Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and cholera toxin (Ctx) secreted by Vibrio cholerae.

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli are a pathotype of Escherichia coli which cause acute and chronic diarrhea in both the developed and developing world. They may also cause urinary tract infections. EAEC are defined by their "stacked-brick" pattern of adhesion to the human laryngeal epithelial cell line HEp-2. The pathogenesis of EAEC involves the aggregation of and adherence of the bacteria to the intestinal mucosa, where they elaborate enterotoxins and cytotoxins that damage host cells and induce inflammation that results in diarrhea.

Bacterial effectors are proteins secreted by pathogenic bacteria into the cells of their host, usually using a type 3 secretion system (TTSS/T3SS), a type 4 secretion system (TFSS/T4SS) or a Type VI secretion system (T6SS). Some bacteria inject only a few effectors into their host’s cells while others may inject dozens or even hundreds. Effector proteins may have many different activities, but usually help the pathogen to invade host tissue, suppress its immune system, or otherwise help the pathogen to survive. Effector proteins are usually critical for virulence. For instance, in the causative agent of plague, the loss of the T3SS is sufficient to render the bacteria completely avirulent, even when they are directly introduced into the bloodstream. Gram negative microbes are also suspected to deploy bacterial outer membrane vesicles to translocate effector proteins and virulence factors via a membrane vesicle trafficking secretory pathway, in order to modify their environment or attack/invade target cells, for example, at the host-pathogen interface.