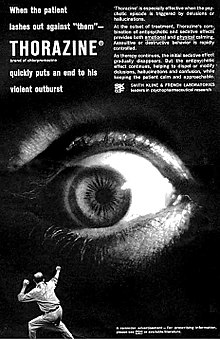

Antipsychotics, previously known as neuroleptics and major tranquilizers, are a class of psychotropic medication primarily used to manage psychosis, principally in schizophrenia but also in a range of other psychotic disorders. They are also the mainstay, together with mood stabilizers, in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Moreover, they are also used as adjuncts in the treatment of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder.

Haloperidol, sold under the brand name Haldol among others, is a typical antipsychotic medication. Haloperidol is used in the treatment of schizophrenia, tics in Tourette syndrome, mania in bipolar disorder, delirium, agitation, acute psychosis, and hallucinations from alcohol withdrawal. It may be used by mouth or injection into a muscle or a vein. Haloperidol typically works within 30 to 60 minutes. A long-acting formulation may be used as an injection every four weeks by people with schizophrenia or related illnesses, who either forget or refuse to take the medication by mouth.

Fluphenazine, sold under the brand name Prolixin among others, is a high-potency typical antipsychotic medication. It is used in the treatment of chronic psychoses such as schizophrenia, and appears to be about equal in effectiveness to low-potency antipsychotics like chlorpromazine. It is given by mouth, injection into a muscle, or just under the skin. There is also a long acting injectable version that may last for up to four weeks. Fluphenazine decanoate, the depot injection form of fluphenazine, should not be used by people with severe depression.

The atypical antipsychotics (AAP), also known as second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and serotonin–dopamine antagonists (SDAs), are a group of antipsychotic drugs largely introduced after the 1970s and used to treat psychiatric conditions. Some atypical antipsychotics have received regulatory approval for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, irritability in autism, and as an adjunct in major depressive disorder.

Risperidone, sold under the brand name Risperdal among others, is an atypical antipsychotic used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It is taken either by mouth or by injection. The injectable versions are long-acting and last for 2–4 weeks.

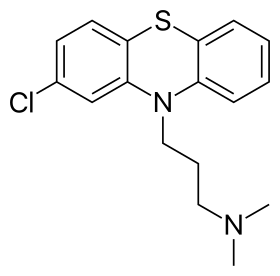

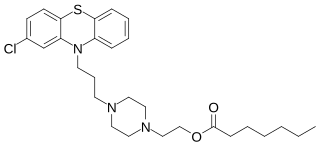

Perphenazine is a typical antipsychotic drug. Chemically, it is classified as a piperazinyl phenothiazine. Originally marketed in the United States as Trilafon, it has been in clinical use for decades.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a disorder that results in involuntary repetitive body movements, which may include grimacing, sticking out the tongue or smacking the lips. Additionally, there may be rapid jerking movements or slow writhing movements. In about 20% of people with TD, the disorder interferes with daily functioning. Reversibility of the condition is determined primarily by severity of symptoms and how long the condition has been present before stopping the offending drug.

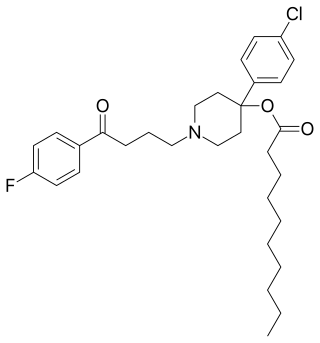

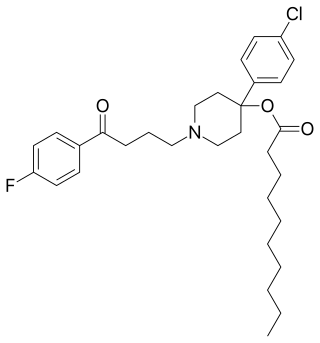

Haloperidol decanoate, sold under the brand name Haldol Decanoate among others, is a typical antipsychotic which is used in the treatment of schizophrenia. It is administered by injection into muscle at a dose of 100 to 200 mg once every 4 weeks or monthly. The dorsogluteal site is recommended. A 3.75-cm (1.5-inch), 21-gauge needle is generally used, but obese individuals may require a 6.5-cm (2.5-inch) needle to ensure that the drug is indeed injected intramuscularly and not subcutaneously. Haloperidol decanoate is provided in the form of 50 or 100 mg/mL oil solution of sesame oil and benzyl alcohol in ampoules or pre-filled syringes. Its elimination half-life after multiple doses is 21 days. The medication is marketed in many countries throughout the world.

Flupentixol influences on brain. Flupentixol (INN), also known as flupenthixol, marketed under brand names such as Depixol and Fluanxol is a typical antipsychotic drug of the thioxanthene class. It was introduced in 1965 by Lundbeck. In addition to single drug preparations, it is also available as flupentixol/melitracen—a combination product containing both melitracen and flupentixol . Flupentixol is not approved for use in the United States. It is, however, approved for use in the UK, Australia, Canada, Russian Federation, South Africa, New Zealand, Philippines, Iran, Germany, and various other countries.

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) are symptoms that are archetypically associated with the extrapyramidal system of the brain's cerebral cortex. When such symptoms are caused by medications or other drugs, they are also known as extrapyramidal side effects (EPSE). The symptoms can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term). They include movement dysfunction such as dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonism characteristic symptoms such as rigidity, bradykinesia, tremor, and tardive dyskinesia. Extrapyramidal symptoms are a reason why subjects drop out of clinical trials of antipsychotics; of the 213 (14.6%) subjects that dropped out of one of the largest clinical trials of antipsychotics, 58 (27.2%) of those discontinuations were due to EPS.

Fluspirilene is a diphenylbutylpiperidine typical antipsychotic drug, used for the treatment of schizophrenia. It is administered intramuscularly. It was discovered at Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1963. A 2007 systematic review investigated the efficacy of fluspirilene decanoate for people with schizophrenia:

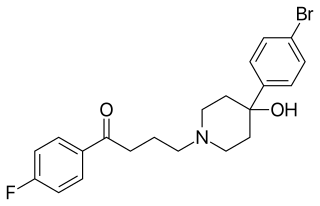

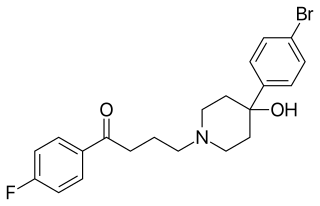

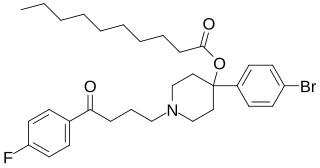

Bromperidol, sold under the brand names Bromidol and Impromen among others, is a typical antipsychotic of the butyrophenone group which is used in the treatment of schizophrenia. It was discovered at Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1966. An ester prodrug, bromperidol decanoate, is a long-acting form of bromperidol used as a depot injectable.

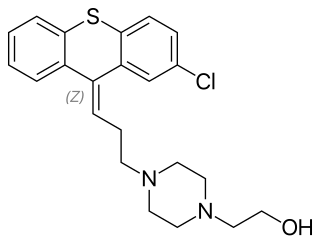

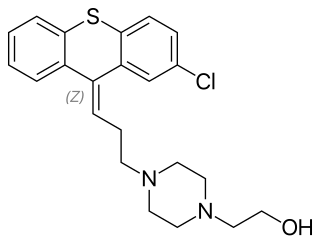

Zuclopenthixol, also known as zuclopentixol, is a medication used to treat schizophrenia and other psychoses. It is classed, pharmacologically, as a typical antipsychotic. Chemically it is a thioxanthene. It is the cis-isomer of clopenthixol. Clopenthixol was introduced in 1961, while zuclopenthixol was introduced in 1978.

Clopenthixol (Sordinol), also known as clopentixol, is a typical antipsychotic drug of the thioxanthene class. It was introduced by Lundbeck in 1961.

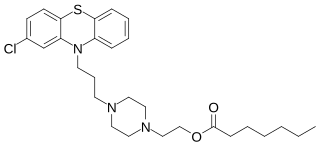

Pipotiazine (Piportil), also known as pipothiazine, is a typical antipsychotic of the phenothiazine class used in the United Kingdom and other countries for the treatment of schizophrenia. Its properties are similar to those of chlorpromazine. A 2004 systematic review investigated its efficacy for people with schizophrenia:

Aripiprazole lauroxil, sold under the brand name Aristada, is a long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic that was developed by Alkermes. It is an N-acyloxymethyl prodrug of aripiprazole that is administered via intramuscular injection once every four to eight weeks for the treatment of schizophrenia. Aripiprazole lauroxil was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 5 October 2015.

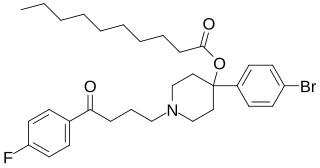

Bromperidol decanoate, sold under the brand names Bromidol Depot, Bromodol Decanoato, and Impromen Decanoas, is an antipsychotic which has been marketed in Europe and Latin America. It is an antipsychotic ester and long-acting prodrug of bromperidol which is administered by depot intramuscular injection once every 4 weeks.

Perphenazine enanthate, sold under the brand name Trilafon Enantat among others, is a typical antipsychotic and a depot antipsychotic ester which is used in the treatment of schizophrenia and has been marketed in Europe. It is formulated in sesame oil and administered by intramuscular injection and acts as a long-lasting prodrug of perphenazine. Perphenazine enanthate is used at a dose of 25 to 200 mg once every 2 weeks by injection, with a time to peak levels of 2 to 3 days and an elimination half-life of 4 to 7 days.

Oxyprothepin decanoate, sold under the brand name Meclopin, is a typical antipsychotic which was used in the treatment of schizophrenia in the Czech Republic but is no longer marketed. It is administered by depot injection into muscle. The medication has an approximate duration of 2 to 3 weeks. The history of oxyprothepin decanoate has been reviewed.

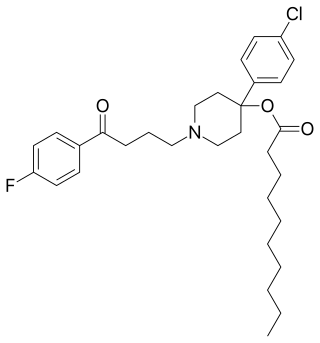

An antipsychotic ester is an ester of an antipsychotic. They are used clinically as prodrugs to increase fat solubility and thereby prolong duration when antipsychotics are used as depot injectables.