Vaginismus is a condition in which involuntary muscle spasm interferes with vaginal intercourse or other penetration of the vagina. This often results in pain with attempts at sex. Often it begins when vaginal intercourse is first attempted. Vaginismus may be considered an older term for pelvic floor dysfunction.

Anorgasmia is a type of sexual dysfunction in which a person cannot achieve orgasm despite adequate stimulation. Anorgasmia is far more common in females than in males and is especially rare in younger men. The problem is greater in women who are post-menopausal. In males, it is most closely associated with delayed ejaculation. Anorgasmia can often cause sexual frustration.

Dyspareunia is painful sexual intercourse due to medical or psychological causes. The term dyspareunia covers both female dyspareunia and male dyspareunia, but many discussions that use the term without further specification concern the female type, which is more common than the male type. In females, the pain can primarily be on the external surface of the genitalia, or deeper in the pelvis upon deep pressure against the cervix. Medically, dyspareunia is a pelvic floor dysfunction and is frequently underdiagnosed. It can affect a small portion of the vulva or vagina or be felt all over the surface. Understanding the duration, location, and nature of the pain is important in identifying the causes of the pain.

Persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD), originally called persistent sexual arousal syndrome (PSAS), is spontaneous, persistent, unwanted and uncontrollable genital arousal in the absence of sexual stimulation or sexual desire, and is typically not relieved by orgasm. Instead, multiple orgasms over hours or days may be required for relief.

Sexual dysfunction is difficulty experienced by an individual or partners during any stage of normal sexual activity, including physical pleasure, desire, preference, arousal, or orgasm. The World Health Organization defines sexual dysfunction as a "person's inability to participate in a sexual relationship as they would wish". This definition is broad and is subject to many interpretations. A diagnosis of sexual dysfunction under the DSM-5 requires a person to feel extreme distress and interpersonal strain for a minimum of six months. Sexual dysfunction can have a profound impact on an individual's perceived quality of sexual life. The term sexual disorder may not only refer to physical sexual dysfunction, but to paraphilias as well; this is sometimes termed disorder of sexual preference.

Pudendal nerve entrapment (PNE), also known as Alcock canal syndrome, is an uncommon source of chronic pain in which the pudendal nerve is entrapped or compressed in Alcock's canal. There are several different types of PNE based on the site of entrapment anatomically. Pain is positional and is worsened by sitting. Other symptoms include genital numbness, fecal incontinence and urinary incontinence.

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease of unknown cause which can affect any body part of any person but has a strong preference for the genitals and is also known as balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO) when it affects the penis. Lichen sclerosus is not contagious. There is a well-documented increase of skin cancer risk in LS, potentially improvable with treatment. LS in adult age women is normally incurable, but improvable with treatment, and often gets progressively worse if not treated properly. Most males with mild or intermediate disease restricted to foreskin or glans can be cured by either medical or surgical treatment.

Vaginal bleeding is any expulsion of blood from the vagina. This bleeding may originate from the uterus, vaginal wall, or cervix. Generally, it is either part of a normal menstrual cycle or is caused by hormonal or other problems of the reproductive system, such as abnormal uterine bleeding.

Vulvitis is inflammation of the vulva, the external female mammalian genitalia that include the labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and introitus. It may co-occur as vulvovaginitis with vaginitis, inflammation of the vagina, and may have infectious or non-infectious causes. The warm and moist conditions of the vulva make it easily affected. Vulvitis is prone to occur in any female especially those who have certain sensitivities, infections, allergies, or diseases that make them likely to have vulvitis. Postmenopausal women and prepubescent girls are more prone to be affected by it, as compared to women in their menstruation period. It is so because they have low estrogen levels which makes their vulvar tissue thin and dry. Women having diabetes are also prone to be affected by vulvitis due to the high sugar content in their cells, increasing their vulnerability. Vulvitis is not a disease, it is just an inflammation caused by an infection, allergy or injury. Vulvitis may also be symptom of any sexually transmitted infection or a fungal infection.

Vaginal discharge is a mixture of liquid, cells, and bacteria that lubricate and protect the vagina. This mixture is constantly produced by the cells of the vagina and cervix, and it exits the body through the vaginal opening. The composition, amount, and quality of discharge varies between individuals and can vary throughout the menstrual cycle and throughout the stages of sexual and reproductive development. Normal vaginal discharge may have a thin, watery consistency or a thick, sticky consistency, and it may be clear or white in color. Normal vaginal discharge may be large in volume but typically does not have a strong odor, nor is it typically associated with itching or pain. While most discharge is considered physiologic or represents normal functioning of the body, some changes in discharge can reflect infection or other pathological processes. Infections that may cause changes in vaginal discharge include vaginal yeast infections, bacterial vaginosis, and sexually transmitted infections. The characteristics of abnormal vaginal discharge vary depending on the cause, but common features include a change in color, a foul odor, and associated symptoms such as itching, burning, pelvic pain, or pain during sexual intercourse.

Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome (VVS), vestibulodynia, or simply vulvar vestibulitis, is vulvodynia localized to the vulvar vestibule. It tends to be associated with a highly localized "burning" or "cutting" type of pain. Until recently, "vulvar vestibulitis" was the term used for localized vulvar pain: the suffix "-itis" would normally imply inflammation, but in fact there is little evidence to support an inflammatory process in the condition. "Vestibulodynia" is the term now recognized by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.

A vaginal disease is a pathological condition that affects part or all of the vagina.

Genital leiomyomas are leiomyomas that originate in the dartos muscles, or smooth muscles, of the genitalia, areola, and nipple. They are a subtype of cutaneous leiomyomas that affect smooth muscle found in the scrotum, labia, or nipple. They are benign tumors, but may cause pain and discomfort to patients. Genital leiomyoma can be symptomatic or asymptomatic and is dependent on the type of leiomyoma. In most cases, pain in the affected area or region is most common. For vaginal leiomyoma, vaginal bleeding and pain may occur. Uterine leiomyoma may exhibit pain in the area as well as painful bowel movement and/or sexual intercourse. Nipple pain, enlargement, and tenderness can be a symptom of nipple-areolar leiomyomas. Genital leiomyomas can be caused by multiple factors, one can be genetic mutations that affect hormones such as estrogen and progesterone. Moreover, risk factors to the development of genital leiomyomas include age, race, and gender. Ultrasound and imaging procedures are used to diagnose genital leiomyomas, while surgically removing the tumor is the most common treatment of these diseases. Case studies for nipple areolar, scrotal, and uterine leiomyoma were used, since there were not enough secondary resources to provide more evidence.

Female genital disease is a disorder of the structure or function of the female reproductive system that has a known cause and a distinctive group of symptoms, signs, or anatomical changes. The female reproductive system consists of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, and vulva. Female genital diseases can be classified by affected location or by type of disease, such as malformation, inflammation, or infection.

In mammals, the vulva consists of the external female genitalia. The human vulva includes the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vulval vestibule, urinary meatus, the vaginal opening, hymen, and Bartholin's and Skene's vestibular glands. The urinary meatus is also included as it opens into the vulval vestibule. The vulva includes the entrance to the vagina, which leads to the uterus, and provides a double layer of protection for this by the folds of the outer and inner labia. Pelvic floor muscles support the structures of the vulva. Other muscles of the urogenital triangle also give support.

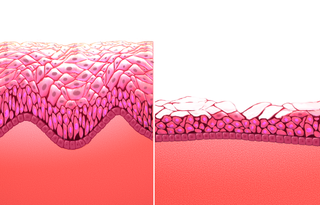

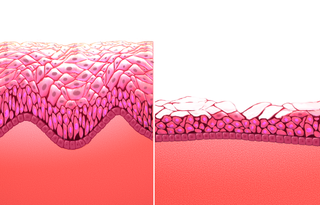

Atrophic vaginitis is inflammation of the vagina as a result of tissue thinning due to not enough estrogen. Symptoms may include pain with sex, vaginal itchiness or dryness, and an urge to urinate or burning with urination. It generally does not resolve without ongoing treatment. Complications may include urinary tract infections.

A vulvar disease is a particular abnormal, pathological condition that affects part or all of the vulva. Several pathologies are defined. Some can be prevented by vulvovaginal health maintenance.

A vestibulectomy is a gynecological surgical procedure that can be used to treat vulvar pain, specifically in cases of provoked vestibulodynia. Vestibulodynia is a chronic pain syndrome that is a subtype of localized vulvodynia where chronic pain and irritation is present in the vulval vestibule, which is near the entrance of the vagina. Vestibulectomy may be partial or complete.

Pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) is a specialty area within physical therapy focusing on the rehabilitation of muscles in the pelvic floor after injury or dysfunction. It can be used to address issues such as muscle weakness or tightness post childbirth, dyspareunia, vaginismus, vulvodynia, constipation, fecal or urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and sexual dysfunction. Licensed physical therapists with specialized pelvic floor physical therapy training address dysfunction in individuals across the gender and sex spectra, though PFPT is often associated with women's health for its heavy focus on addressing issues of pelvic trauma after childbirth.