Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Lyceum, the Peripatetic school of philosophy, and the Aristotelian tradition. His writings cover many subjects including physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theatre, music, rhetoric, psychology, linguistics, economics, politics, meteorology, geology, and government. Aristotle provided a complex synthesis of the various philosophies existing prior to him. It was above all from his teachings that the West inherited its intellectual lexicon, as well as problems and methods of inquiry. As a result, his philosophy has exerted a unique influence on almost every form of knowledge in the West and it continues to be a subject of contemporary philosophical discussion.

Ibn Rushd, often Latinized as Averroes, was an Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence and law, and linguistics. The author of more than 100 books and treatises, his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle, for which he was known in the western world as The Commentator and Father of Rationalism. Ibn Rushd also served as a chief judge and a court physician for the Almohad Caliphate.

Early Islamic philosophy or classical Islamic philosophy is a period of intense philosophical development beginning in the 2nd century AH of the Islamic calendar and lasting until the 6th century AH. The period is known as the Islamic Golden Age, and the achievements of this period had a crucial influence in the development of modern philosophy and science. For Renaissance Europe, "Muslim maritime, agricultural, and technological innovations, as well as much East Asian technology via the Muslim world, made their way to western Europe in one of the largest technology transfers in world history.” This period starts with al-Kindi in the 9th century and ends with Averroes at the end of 12th century. The death of Averroes effectively marks the end of a particular discipline of Islamic philosophy usually called the Peripatetic Arabic School, and philosophical activity declined significantly in Western Islamic countries, namely in Islamic Spain and North Africa, though it persisted for much longer in the Eastern countries, in particular Persia and India where several schools of philosophy continued to flourish: Avicennism, Illuminationist philosophy, Mystical philosophy, and Transcendent theosophy.

Abu Nasr Al-Farabi known in the West as Alpharabius; was a renowned early Islamic philosopher and jurist who wrote in the fields of political philosophy, metaphysics, ethics and logic. He was also a scientist, cosmologist, mathematician and music theorist.

Averroism refers to a school of medieval philosophy based on the application of the works of 12th-century Andalusian philosopher Averroes, a commentator on Aristotle, in 13th-century Latin Christian scholasticism.

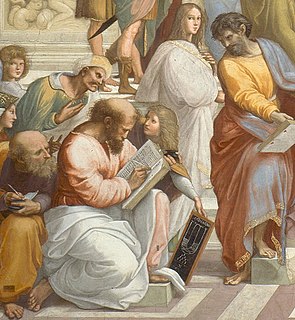

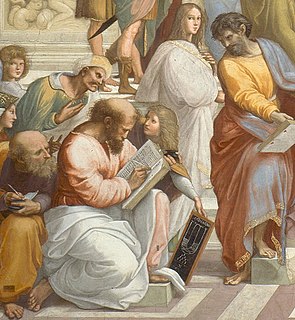

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton. Early Pythagorean communities spread throughout Magna Graecia.

Franciscus Patricius was a philosopher and scientist from the Republic of Venice, originating from Cres. He was known as a defender of Platonism and an opponent of Aristotelianism.

Aristotelianism is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the social sciences under a system of natural law. It answers why-questions by a scheme of four causes, including purpose or teleology, and emphasizes virtue ethics. Aristotle and his school wrote tractates on physics, biology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theatre, music, rhetoric, psychology, linguistics, economics, politics, and government. Any school of thought that takes one of Aristotle's distinctive positions as its starting point can be considered "Aristotelian" in the widest sense. This means that different Aristotelian theories may not have much in common as far as their actual content is concerned besides their shared reference to Aristotle.

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle, and peripatetic is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

The designation "Renaissance philosophy" is used by scholars of intellectual history to refer to the thought of the period running in Europe roughly between 1355 and 1650. It therefore overlaps both with late medieval philosophy, which in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was influenced by notable figures such as Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham, and Marsilius of Padua, and early modern philosophy, which conventionally starts with René Descartes and his publication of the Discourse on Method in 1637.

Christian humanism regards humanist principles like universal human dignity, individual freedom, and the importance of happiness as essential and principal or even exclusive components of the teachings of Jesus. Proponents of the term trace the concept to the Renaissance or patristic period, linking their beliefs to the scholarly movement also called 'humanism'.

Early Islamic law placed importance on formulating standards of argument, which gave rise to a "novel approach to logic" in Kalam . However, with the rise of the Mu'tazili philosophers, who highly valued Aristotle's Organon, this approach was displaced by the older ideas from Hellenistic philosophy. The works of al-Farabi, Avicenna, al-Ghazali and other Persian Muslim logicians who often criticized and corrected Aristotelian logic and introduced their own forms of logic, also played a central role in the subsequent development of European logic during the Renaissance.

John Philoponus, also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Byzantine Greek philologist, Aristotelian commentator, Christian theologian and an author of a considerable number of philosophical treatises and theological works. He was born in Alexandria. A rigorous, sometimes polemical writer and an original thinker who was controversial in his own time, John Philoponus broke from the Aristotelian–Neoplatonic tradition, questioning methodology and eventually leading to empiricism in the natural sciences. He was one of the first to propose a "theory of impetus" similar to the modern concept of inertia over Aristotelian dynamics.

Nous, sometimes equated to intellect or intelligence, is a concept from classical philosophy for the faculty of the human mind necessary for understanding what is true or real.

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings as the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

Byzantine philosophy refers to the distinctive philosophical ideas of the philosophers and scholars of the Byzantine Empire, especially between the 8th and 15th centuries. It was characterised by a Christian world-view, but one which could draw ideas directly from the Greek texts of Plato, Aristotle, and the Neoplatonists.

Commentaries on Aristotle refers to the great mass of literature produced, especially in the ancient and medieval world, to explain and clarify the works of Aristotle. The pupils of Aristotle were the first to comment on his writings, a tradition which was continued by the Peripatetic school throughout the Hellenistic period and the Roman era. The Neoplatonists of the late Roman empire wrote many commentaries on Aristotle, attempting to incorporate him into their philosophy. Although Ancient Greek commentaries are considered the most useful, commentaries continued to be written by the Christian scholars of the Byzantine Empire and by the many Islamic philosophers and Western scholastics who had inherited his texts.

Neoplatonism is a philosophical and religious system, beginning with the work of Plotinus in c. 245 AD, that analyzes and teaches interpretations of the philosophy and theology of Plato, and which extended the interpretations of Plato that middle Platonists developed between c. 80 to c. 245 AD. The English term 'neoplatonism', or 'Neo-Platonism', or 'Neoplatonism' comes from 18th and 19th century Germanic scholars who wanted to systematize history into nameable periods.

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, understood as a project of independent philosophical inquiry, began in Baghdad, in the middle of the 8th century, and in France, in the itinerant court of Charlemagne, in the last quarter of the 8th century. It is defined partly by the process of rediscovering the ancient culture developed in Greece and Rome during the Classical period, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate sacred doctrine with secular learning.

Dutch philosophy is a broad branch of philosophy that discusses the contributions of Dutch philosophers to the discourse of Western philosophy and Renaissance philosophy. The philosophy, as its own entity, arose in the 16th and 17th centuries through the philosophical studies of Desiderius Erasmus and Baruch Spinoza. The adoption of the humanistic perspective by Erasmus, despite his Christian background, and rational but theocentric perspective expounded by Spinoza, supported each of these philosopher's works. In general, the philosophy revolved around acknowledging the reality of human self-determination and rational thought rather than focusing on traditional ideals of fatalism and virtue raised in Christianity. The roots of philosophical frameworks like the mind-body dualism and monism debate can also be traced to Dutch philosophy, which is attributed to 17th century philosopher René Descartes. Descartes was both a mathematician and philosopher during the Dutch Golden Age, despite being from the Kingdom of France. Modern Dutch philosophers like D.H. Th. Vollenhoven provided critical analyses on the dichotomy between dualism and monism.