Background

Brewing in New York City

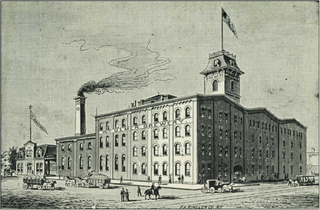

New York City historically was a major center of beer production in the United States. In 1898, the borough of Brooklyn was home to 48 breweries, and during their height, two of the largest Brooklyn-based brewing companies (the F. & M. Schaefer Brewing Company and S. Liebmann & Sons) both annually produced over 2 million barrels of beer. [1] In 1949, approximately 7,000 brewery workers in the city were members of the United Brewery, Flour, Cereal and Soft Drink Workers Union (also simply known as the Brewery Workers Union [2] ), an affiliate union of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. [3] According to a union representative, the workers represented included all levels of workers except salesmen and white-collar workers. [4] These union members, organized into 7 different local unions, [5] worked for 14 major brewing companies in the city and were collectively part of a labor contract between the union and the Brewers Board of Trade, of which the brewing companies were members. [3] These companies included the 10 following breweries: [6]

- Burke

- Ebling [7]

- Edelbrew [8]

- Liebmann

- Metropolis [9]

- Piel Brothers

- Rubsam & Horrmann

- Ruppert

- Schaefer

- Trommer

Additionally, four distributors for the companies Anheuser-Busch, Ballantine, Schlitz, and West End were a part of this board. [6] Many of these companies were located in Brooklyn. [10]

Labor contract disputes

The contract between the union and companies was set to expire at midnight on March 31 of that year, and in the month leading up to that, representatives from both sides met in several rounds of negotiations to discuss the contents of a new deal. However, these talks were bogged down, as the two sides could not agree to the provisions of the contract. [3] In particular, union officials were pushing for an $8.50 weekly raise to the base $71 weekly pay. Workers also wanted a five-hour reduction to their 40-hour work weeks, the addition of an extra man on delivery trucks operated by only one person, and a pension plan. [10] Additional points of contention concerned job security and workplace safety. [10] According to union counsel Paul O'Dwyer (brother to then-New York City Mayor William O'Dwyer [11] ), the main issue concerning the union members was that "there are too many injuries because the men are forced to move the machines too fast and to handle excessive weights without aid on delivery". [4] O'Dwyer also claimed that 20 brewery workers had been killed on the job in New York City over the previous four years and that injuries and workplace hazards had increased. [12] However, a representative of the brewers objected to these claims, arguing that the brewery workers had a good safety record. Additionally, he alleged that the $8.50 raise was unrealistic and that the union had not submitted a counterproposal to the Brewers Board's $2 per week raise counteroffer. [4]

On March 25, union members voted on whether or not to perform a strike action sometime after April 1 if a contract were not agreed to by then. [3] Additionally, on March 27, union members voted by acclamation to request approval from the union's international officials to call a strike after the contract expired. [13] Following this, a vote to approve strike action was held in a closed meeting on March 31. [10] As the expiration date loomed, company and union officials continued to meet and discuss contract proposals, [13] and immediately prior to the contract's expiration, the two parties had been engaged in a 12-hour long Federal mediation session which still failed to achieve a new deal. [4] The strike action would be the second in 5 months for the New York City brewers, [5] as the union led a 29-day strike in October and November 1948 after several delivery drivers were suspended and fired for not meeting company-imposed delivery schedules. [3] As no deal had been reached by the current deal's expiration, the strike commenced at 2:05 a.m. on April 1, 1949. [14]