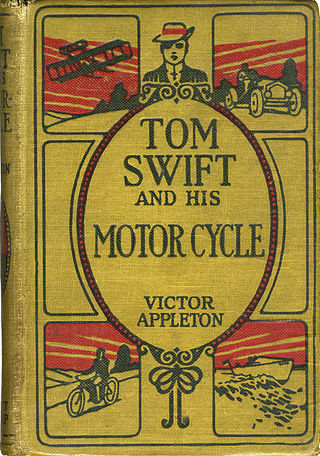

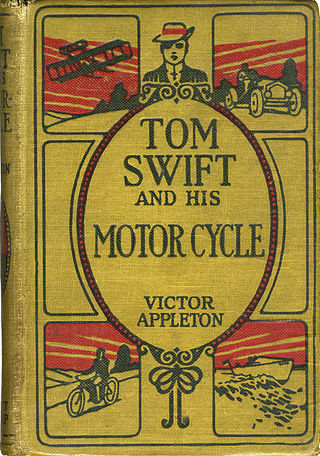

Tom Swift is the main character of six series of American juvenile science fiction and adventure novels that emphasize science, invention, and technology. Inaugurated in 1910, the sequence of series comprises more than 100 volumes. The first Tom Swift – later, Tom Swift Sr. – was created by Edward Stratemeyer, the founder of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a book packaging firm. Tom's adventures have been written by various ghostwriters, beginning with Howard Garis. Most of the books are credited to the collective pseudonym "Victor Appleton". The 33 volumes of the second series use the pseudonym Victor Appleton II for the author. For this series, and some later ones, the main character is "Tom Swift Jr." New titles have been published again from 2019 after a gap of about ten years, roughly the time that has passed before every resumption. Most of the series emphasized Tom's inventions. The books generally describe the effects of science and technology as wholly beneficial, and the role of the inventor in society as admirable and heroic.

Mildred Augustine Wirt Benson was an American journalist and writer of children's books. She wrote some of the earliest Nancy Drew mysteries and created the detective's adventurous personality. Benson wrote under the Stratemeyer Syndicate pen name, Carolyn Keene, from 1929 to 1947 and contributed to 23 of the first 30 Nancy Drew mysteries, which were bestsellers.

Carolyn Keene is the pseudonym of the authors of the Nancy Drew mystery stories and The Dana Girls mystery stories, both produced by the Stratemeyer Syndicate. In addition, the Keene pen name is credited with the Nancy Drew spin-off, River Heights, and the Nancy Drew Notebooks.

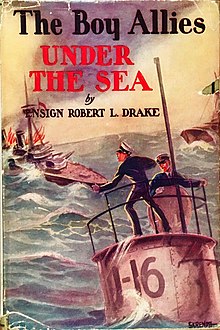

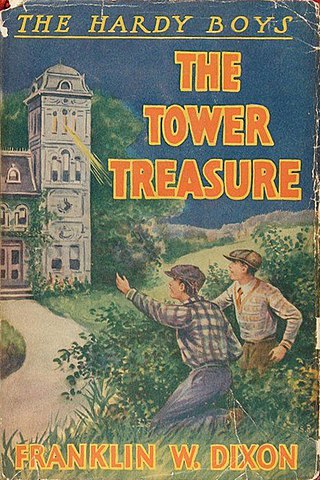

The Stratemeyer Syndicate was a publishing company that produced a number of mystery book series for children, including Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys, the various Tom Swift series, the Bobbsey Twins, the Rover Boys, and others. They published and contracted the many pseudonymous authors doing the writing of the series from 1899 through 1987, when the syndicate partners sold the company to Simon & Schuster.

Horatio Alger Jr. was an American author who wrote young adult novels about impoverished boys and their rise from humble backgrounds to middle-class security and comfort through good works. His writings were characterized by the "rags-to-riches" narrative, which had a formative effect on the United States from 1868 through to his death in 1899.

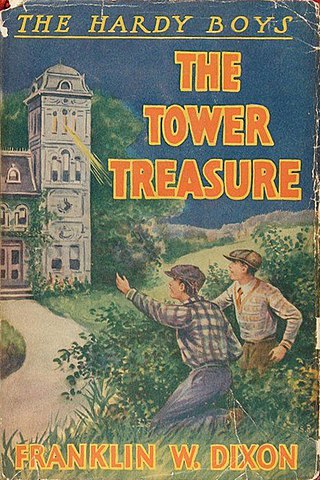

The Hardy Boys, brothers Frank and Joe Hardy, are fictional characters who appear in several mystery series for children and teens. The series revolves around teenagers who are amateur sleuths, solving cases that stumped their adult counterparts. The characters were created by American writer Edward Stratemeyer, the founder of book packaging firm Stratemeyer Syndicate. The books were written by several ghostwriters, most notably Leslie McFarlane, under the collective pseudonym Franklin W. Dixon.

Howard Roger Garis was an American author, best known for a series of books that featured the character of Uncle Wiggily Longears, an engaging elderly rabbit. Many of his books were illustrated by Lansing Campbell. Garis and his wife, Lilian Garis, were possibly the most prolific children's authors of the early 20th century.

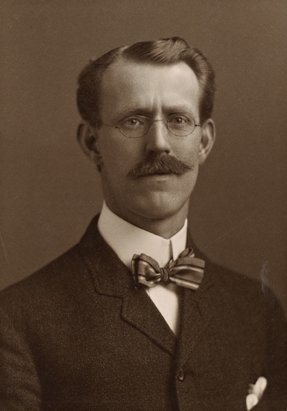

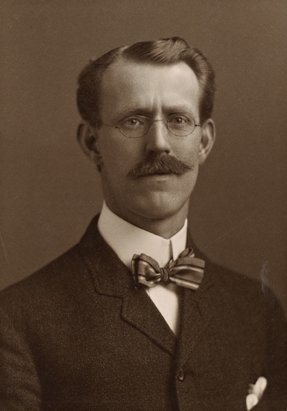

Edward L. Stratemeyer was an American publisher, writer of children's fiction, and founder of the Stratemeyer Syndicate. He was one of the most prolific writers in the world, producing in excess of 1,300 books himself, selling in excess of 500 million copies. He also created many well-known fictional book series for juveniles, including The Rover Boys, The Bobbsey Twins, Tom Swift, The Hardy Boys, and Nancy Drew series, many of which sold millions of copies and remain in publication. On Stratemeyer's legacy, Fortune wrote: "As oil had its Rockefeller, literature had its Stratemeyer."

Radio Boys was the title of three series of juvenile fiction books published by rival companies in the United States in the 1920s:

Grosset & Dunlap is a New York City-based publishing house founded in 1898.

Charles Nuttall was a prolific Australian artist, writer and radio broadcaster. He spent much of his working life in Melbourne, apart from a period in New York City from 1905 to 1910.

The Nancy Drew Mystery Stories is the long-running "main" series of the Nancy Drew franchise, which was published under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene. There are 175 novels — plus 34 revised stories — that were published between 1930 and 2003 under the banner; Grosset & Dunlap published the first 56, and 34 revised stories, while Simon & Schuster published the series beginning with volume 57.

Frank V. Webster was a pseudonym used by the Stratemeyer Syndicate. A total of 25 novels in The Webster Series For Boys were published by Cupples & Leon between 1909 and 1915. Titles were reprinted in 1938 by Saalfield Publishing.

Walter Stanton Rogers was one of the primary illustrators used by the Stratemeyer Syndicate for its children's book series from the 1910s-1930s. For many collectors, Rogers, "with his many wonderful full-color dust jackets," was "a benchmark for a successful series-book illustrator."

Cupples & Leon was an American publishing company founded in 1902 by Victor I. Cupples (1864–1941) and Arthur T. Leon (1867–1943). They published juvenile fiction and children's books but are mainly remembered today as the major publisher of books collecting comic strips during the early decades of the 20th century.

Albert Capwell Wyckoff was an ordained minister of the Presbyterian Church in the United States and a writer of juvenile fiction, most notably the Mercer Boys series and Mystery Hunter series.

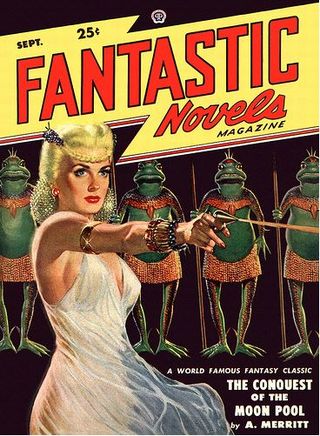

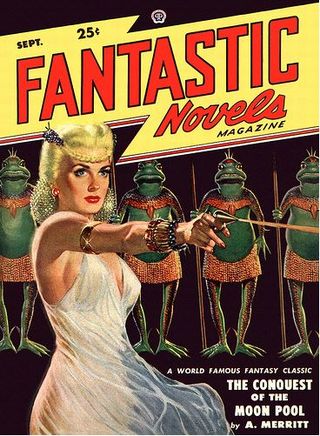

Fantastic Novels was an American science fiction and fantasy pulp magazine published by the Munsey Company of New York from 1940 to 1941, and again by Popular Publications, also of New York, from 1948 to 1951. It was a companion to Famous Fantastic Mysteries. Like that magazine, it mostly reprinted science fiction and fantasy classics from earlier decades, such as novels by A. Merritt, George Allan England, and Victor Rousseau, though it occasionally published reprints of more recent work, such as Earth's Last Citadel, by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore.

Charles Stanley Strong was an American writer, adventurer and explorer.

Girl detective is a genre of detective fiction featuring a young, often teen-aged, female protagonist who solves crimes as a hobby.