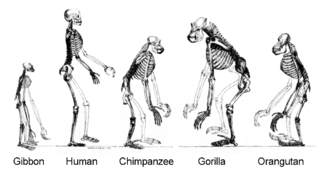

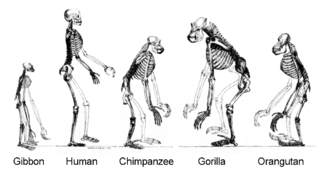

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of Homo sapiens as a distinct species of the hominid family that includes all the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of traits such as human bipedalism, dexterity, and complex language, as well as interbreeding with other hominins, indicating that human evolution was not linear but weblike. The study of the origins of humans involves several scientific disciplines, including physical and evolutionary anthropology, paleontology, and genetics; the field is also known by the terms anthropogeny, anthropogenesis, and anthropogony.

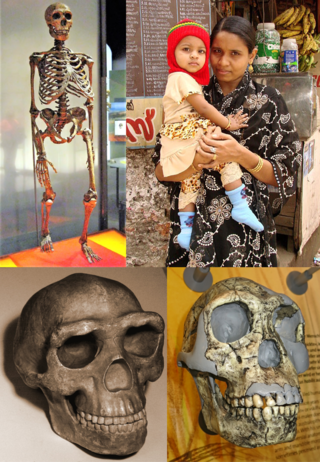

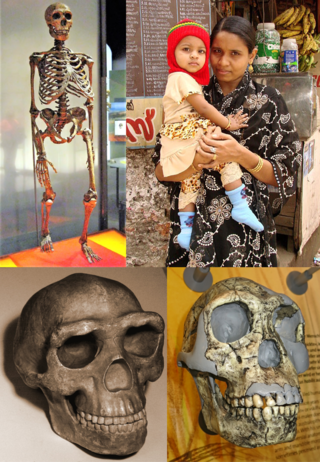

Early modern human (EMH), or anatomically modern human (AMH), are terms used to distinguish Homo sapiens that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans, from extinct archaic human species. This distinction is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe. Among the oldest known remains of Homo sapiens are those found at the Omo-Kibish I archaeological site in south-western Ethiopia, dating to about 233,000 to 196,000 years ago, the Florisbad site in South Africa, dating to about 259,000 years ago, and the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco, dated about 315,000 years ago.

Genome projects are scientific endeavours that ultimately aim to determine the complete genome sequence of an organism and to annotate protein-coding genes and other important genome-encoded features. The genome sequence of an organism includes the collective DNA sequences of each chromosome in the organism. For a bacterium containing a single chromosome, a genome project will aim to map the sequence of that chromosome. For the human species, whose genome includes 22 pairs of autosomes and 2 sex chromosomes, a complete genome sequence will involve 46 separate chromosome sequences.

Homo is a genus of great ape that emerged from the genus Australopithecus and encompasses only a single extant species, Homo sapiens, along with a number of extinct species classified as either ancestral or closely related to modern humans; these include Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis. The oldest member of the genus is Homo habilis, with records of just over 2 million years ago. Homo, together with the genus Paranthropus, is probably most closely related to the species Australopithecus africanus within Australopithecus. The closest living relatives of Homo are of the genus Pan, with the ancestors of Pan and Homo estimated to have diverged around 5.7-11 million years ago during the Late Miocene.

The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology is a research institute based in Leipzig, Germany, that was founded in 1997. It is part of the Max Planck Society network.

Paleogenetics is the study of the past through the examination of preserved genetic material from the remains of ancient organisms. Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling introduced the term in 1963, long before the sequencing of DNA, in reference to the possible reconstruction of the corresponding polypeptide sequences of past organisms. The first sequence of ancient DNA, isolated from a museum specimen of the extinct quagga, was published in 1984 by a team led by Allan Wilson.

The timeline of human evolution outlines the major events in the evolutionary lineage of the modern human species, Homo sapiens, throughout the history of life, beginning some 4 billion years ago down to recent evolution within H. sapiens during and since the Last Glacial Period.

Archaic humans is a broad category denoting all species of the genus Homo that are not Homo sapiens. Among the earliest modern human remains are those from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, Florisbad in South Africa (259 ka), Omo-Kibish I in southern Ethiopia, and Apidima Cave in Southern Greece. Some examples of archaic humans include H. antecessor (1200–770 ka), H. bodoensis (1200–300 ka), H. heidelbergensis (600–200 ka), Neanderthals, H. rhodesiensis (300–125 ka) and Denisovans.

Human evolutionary genetics studies how one human genome differs from another human genome, the evolutionary past that gave rise to the human genome, and its current effects. Differences between genomes have anthropological, medical, historical and forensic implications and applications. Genetic data can provide important insights into human evolution.

The Neanderthal genome project is an effort of a group of scientists to sequence the Neanderthal genome, founded in July 2006.

Early human migrations are the earliest migrations and expansions of archaic and modern humans across continents. They are believed to have begun approximately 2 million years ago with the early expansions out of Africa by Homo erectus. This initial migration was followed by other archaic humans including H. heidelbergensis, which lived around 500,000 years ago and was the likely ancestor of Denisovans and Neanderthals as well as modern humans. Early hominids had likely crossed land bridges that have now sunk.

The evolution of the brain refers to the progressive development and complexity of neural structures over millions of years, resulting in the diverse range of brain sizes and functions observed across different species today, particularly in vertebrates.

Bruce Lahn is a Chinese-born American geneticist. Lahn came to the U.S. from China to continue his education in the late 1980s. He is the William B. Graham professor of Human Genetics at the University of Chicago. He is also the founder of the Center for Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China. Lahn currently serves as the chief scientist of VectorBuilder, Inc.

In paleoanthropology, the recent African origin of modern humans or the "Out of Africa" theory (OOA) is the most widely accepted model of the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans. It follows the early expansions of hominins out of Africa, accomplished by Homo erectus and then Homo neanderthalensis.

The multiregional hypothesis, multiregional evolution (MRE), or polycentric hypothesis, is a scientific model that provides an alternative explanation to the more widely accepted "Out of Africa" model of monogenesis for the pattern of human evolution.

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic, and lived, based on current evidence, from 285 to 25 thousand years ago. Denisovans are known from few physical remains; consequently, most of what is known about them comes from DNA evidence. No formal species name has been established pending more complete fossil material.

Adam David Rutherford is a British geneticist and science populariser. He was an audio-visual content editor for the journal Nature for a decade, and is a frequent contributor to the newspaper The Guardian. He formerly hosted the BBC Radio 4 programmes Inside Science and The Curious Cases of Rutherford and Fry; has produced several science documentaries; and has published books related to genetics and the origin of life.

Recent human evolution refers to evolutionary adaptation, sexual and natural selection, and genetic drift within Homo sapiens populations, since their separation and dispersal in the Middle Paleolithic about 50,000 years ago. Contrary to popular belief, not only are humans still evolving, their evolution since the dawn of agriculture is faster than ever before. It has been proposed that human culture acts as a selective force in human evolution and has accelerated it; however, this is disputed. With a sufficiently large data set and modern research methods, scientists can study the changes in the frequency of an allele occurring in a tiny subset of the population over a single lifetime, the shortest meaningful time scale in evolution. Comparing a given gene with that of other species enables geneticists to determine whether it is rapidly evolving in humans alone. For example, while human DNA is on average 98% identical to chimp DNA, the so-called Human Accelerated Region 1 (HAR1), involved in the development of the brain, is only 85% similar.

Carles Lalueza Fox is a Spanish biologist specialized in the study of ancient DNA. A doctor in Biology for the University of Barcelona, he worked in Cambridge and Oxford as well as in the private genetics company CODE Genetics of Iceland. Since 2008, he has served as a research Scientist in the Institute of Evolutionary Biology.

The Loschbour man is a specimen of Homo sapiens from the European Mesolithic discovered in 1935 in Mullerthal, in the commune of Waldbillig, Luxembourg.