Related Research Articles

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 123 years. The partitions were conducted by the Habsburg monarchy, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Russian Empire, which divided up the Commonwealth lands among themselves progressively in the process of territorial seizures and annexations.

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed during late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages in Europe and lasted in some countries until the mid-19th century.

From 1795 to 1918, Poland was split between Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and Russia and had no independent existence. In 1795 the third and the last of the three 18th-century partitions of Poland ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Nevertheless, events both within and outside the Polish lands kept hopes for restoration of Polish independence alive throughout the 19th century. Poland's geopolitical location on the Northern European Lowlands became especially important in a period when its expansionist neighbors, the Kingdom of Prussia and Imperial Russia, involved themselves intensely in European rivalries and alliances as modern nation-states took form over the entire continent.

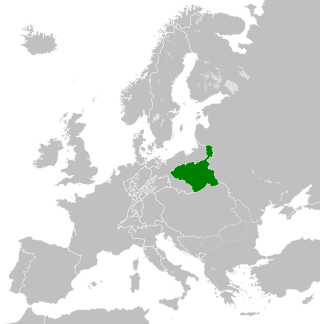

The Duchy of Warsaw, also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars. It initially comprised the ethnically Polish lands ceded to France by Prussia under the terms of the Treaties of Tilsit, and was augmented in 1809 with territory ceded by Austria in the Treaty of Schönbrunn. It was the first attempt to re-establish Poland as a sovereign state after the 18th-century partitions and covered the central and southeastern parts of present-day Poland.

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last insurgents were captured by the Russian forces in 1864.

The Kościuszko Uprising, also known as the Polish Uprising of 1794, Second Polish War, Polish Campaign of 1794, and the Polish Revolution of 1794, was an uprising against the Russian and Prussian influence on the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, led by Tadeusz Kościuszko in Poland-Lithuania and the Prussian partition in 1794. It was a failed attempt to liberate the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from external influence after the Second Partition of Poland (1793) and the creation of the Targowica Confederation.

The Kraków uprising of 1846 was an attempt, led by Polish insurgents such as Jan Tyssowski and Edward Dembowski, to incite a fight for national independence. The uprising was centered on the city of Kraków, the capital of a small state of Free City of Krakow. It was directed at the powers that partitioned Poland, in particular the nearby Austrian Empire. The uprising lasted about nine days and ended with an Austrian victory.

The emancipation reform of 1861 in Russia, also known as the Edict of Emancipation of Russia, was the first and most important of the liberal reforms enacted during the reign of Emperor Alexander II of Russia. The reform effectively abolished serfdom throughout the Russian Empire.

The Greater Poland uprising of 1848 or Poznań Uprising was an unsuccessful military insurrection of Poles against forces of the Kingdom of Prussia, during the Revolutions of 1848. The main fighting in the Prussian Partition of Poland was concentrated in the Greater Poland region but some fighting also occurred in Pomerelia. In addition, protests were also held in Polish inhabited regions of Silesia.

The term serf, in the sense of an unfree peasant of tsarist Russia, meant an unfree person who, unlike a slave, historically could be sold only together with the land to which they were "attached". However, this stopped being a requirement by the 19th century, and serfs were practically indistinguishable from slaves. Contemporary legal documents, such as Russkaya Pravda, distinguished several degrees of feudal dependency of peasants. While another form of slavery in Russia, kholopstvo, was ended by Peter I in 1723, the serfdom was abolished only by Alexander II's emancipation reform of 1861; nevertheless, in times past, the state allowed peasants to sue for release from serfdom under certain conditions, and also took measures against abuses of landlord power.

The Proclamation of Połaniec, issued on 7 May 1794 by Tadeusz Kościuszko near the town of Połaniec, was one of the most notable events of Poland's Kościuszko Uprising, and the most famous legal act of the Uprising. It partially abolished serfdom in Poland, granting substantial civil liberties to all the peasants. The motives behind the Połaniec Proclamation were twofold: first, Kosciuszko, a radical and reformer, believed that serfdom was an unfair system and should be ended; second, the uprising was in desperate need of recruits, and freeing the peasants would prompt many to enlist.

There were many resistance movements in partitioned Poland between 1795 and 1918. Although some of the szlachta was reconciled to the end of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, the possibility of Polish independence was kept alive by events within and without Poland throughout the 19th century. Poland's location on the North European Plain became especially significant in a period when its neighbours, the Kingdom of Prussia and Russia were intensely involved in European rivalries and alliances and modern nation states took form over the entire continent.

The Prussian Partition, or Prussian Poland, is the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired during the Partitions of Poland, in the late 18th century by the Kingdom of Prussia. The Prussian acquisition amounted to 141,400 km2 of land constituting formerly western territory of the Commonwealth. The first partitioning led by imperial Russia with Prussian participation took place in 1772; the second in 1793, and the third in 1795, resulting in Poland's elimination as a state for the next 123 years.

From the 1680s to 1789, Germany comprised many small territories which were parts of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Prussia finally emerged as dominant. Meanwhile, the states developed a classical culture that found its greatest expression in the Enlightenment, with world class leaders such as philosophers Leibniz and Kant, writers such as Goethe and Schiller, and musicians Bach and Beethoven.

The History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–1795) is concerned with the final decades of existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The period, during which the declining state pursued wide-ranging reforms and was subjected to three partitions by the neighboring powers, coincides with the election and reign of the federation's last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski.

Serfdom in Poland became the dominant form of relationship between peasants and nobility in early modern Poland during the 16th-18th centuries, and was a major feature of the economy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, although its origins can be traced back to the 12th century.

The Sejm of the Grand Duchy of Posen was the parliament in the 19th century Grand Duchy of Posen and the Province of Posen, seated in Poznań/Posen. It existed from 1823 to 1918. In the history of the Polish parliament, it succeeded the general sejm and local sejmik on part of the territories of the Prussian partition. Originally retaining a Polish character, it acquired a more German character in the second half of the 19th century.

Serfdom has a long history that dates to ancient times.

The Third Statute of Lithuania abolished slavery in 1588. Serfdom or baudžiava which is, in turn, derived from Lithuanian bausmė (punishment) on the territory of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, continued to exist throughout Rzeczpospolita period and later under the rule of Russian empire until Emancipation reform of 1861.

The government reforms imposed by Tsar Alexander II of Russia, often called the Great Reforms by historians, were a series of major social, political, legal and governmental reforms in the Russian Empire carried out in the 1860s.

References

- ↑ "The Unusual Story of Thaddeus Kosciusko". www.lituanus.org. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego. Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.389-394

- ↑ W.O. Henderson (2005). Studies in the Economic Policy of Frederick the Great. Taylor & Francis. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-415-38203-8.

- ↑ Kantowicz, Edward R. (1975). Polish-American politics in Chicago, 1888-1940 . University of Chicago Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-226-42380-7 . Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ Anderson, Kevin (15 May 2010). Marx at the margins: on nationalism, ethnicity, and non-western societies. University of Chicago Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-226-01983-3 . Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ Smith, William Frank (November 2010). Catholic Church Milestones: People and Events That Shaped the Institutional Church. Dog Ear Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-60844-821-0 . Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ Kamusella, Tomasz (2007). Silesia and Central European nationalisms: the emergence of national and ethnic groups in Prussian Silesia and Austrian Silesia, 1848-1918. Purdue University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-55753-371-5 . Retrieved 30 January 2012.