Éamon de Valera was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of government and head of state and had a leading role in introducing the 1937 Constitution of Ireland.

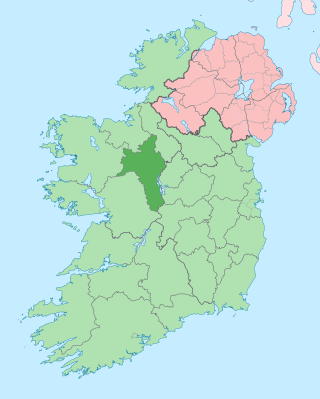

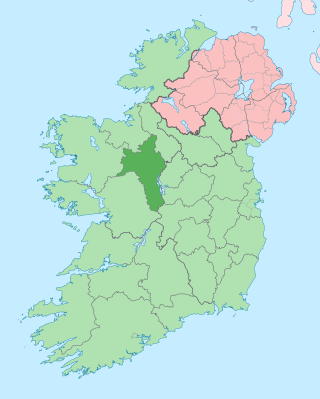

County Roscommon is a county in Ireland. It is part of the province of Connacht and the Northern and Western Region. It is the 11th largest Irish county by area and 26th most populous. Its county town and largest town is Roscommon. Roscommon County Council is the local authority for the county. The population of the county was 69,995 as of the 2022 census.

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the government of the Irish Republic that concluded the Irish War of Independence. It provided for the establishment of the Irish Free State within a year as a self-governing dominion within the "community of nations known as the British Empire", a status "the same as that of the Dominion of Canada". It also provided Northern Ireland, which had been created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, an option to opt out of the Irish Free State, which was exercised by the Parliament of Northern Ireland.

The Second Dáil was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 16 August 1921 until 8 June 1922. From 1919 to 1922, Dáil Éireann was the revolutionary parliament of the self-proclaimed Irish Republic. The Second Dáil consisted of members elected at the 1921 elections, but with only members of Sinn Féin taking their seats. On 7 January 1922, it ratified the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64 votes to 57 which ended the War of Independence and led to the establishment of the Irish Free State on 6 December 1922.

The Irish Oath of Allegiance was a controversial provision in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which Irish TDs and Senators were required to swear before taking their seats in Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann before the Constitution Act 1933 was passed on 3 May 1933. The controversy surrounding the Oath was one of the principal issues that led to the Irish Civil War of 1922–23 between supporters and opponents of the Treaty.

The Declaration of Independence was a document adopted by Dáil Éireann, the revolutionary parliament of the Irish Republic, at its first meeting in the Mansion House, Dublin, on 21 January 1919. It followed from the Sinn Féin election manifesto of December 1918. Texts of the declaration were adopted in three languages: Irish, English and French.

Seán Mac Eoin was an Irish republican and later Fine Gael politician who was Minister for Defence briefly in 1951 and from 1954 to 1957, and Minister for Justice from 1948 to 1951. He had been Chief of Staff of the Defence Forces from February 1929 to October 1929. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1921 to 1923 and from 1929 to 1965.

Ballinasloe is a town in the easternmost part of County Galway in Connacht. Located at an ancient crossing point on the River Suck, evidence of ancient settlement in the area includes a number of Bronze Age sites. Built around a 12th-century castle, which defended the fording point, the modern town of Ballinasloe was "founded" in the early 13th century. As of the 2016 census, it was one of the largest towns in County Galway, with a population of 6,662 people.

Events from the year 1927 in Ireland.

Patrick James Hogan was an Irish Fine Gael politician who served Minister for Agriculture from 1922 to 1924 and 1930 to 1932, Minister for Agriculture and Lands from 1924 to 1930 and Minister for Labour from July 1922 to October 1922. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Galway constituency from 1921 to 1936.

William Joseph Mellows was an Irish republican and Sinn Féin politician. Born in England to an English father and Irish mother, he grew up in Ashton-under-Lyne before moving to Ireland, being raised in Cork, Dublin and his mother's native Wexford. He was active with the Irish Republican Brotherhood and Irish Volunteers, and participated in the Easter Rising in County Galway and the War of Independence. Elected as a TD to the First Dáil, he rejected the Anglo-Irish Treaty. During the Irish Civil War Mellows was captured by Pro-Treaty forces after the surrender of the Four Courts in June 1922. On 8 December 1922 he was one of four senior IRA men executed by the Provisional Government.

Joseph O'Doherty was an Irish teacher, barrister, revolutionary, politician, county manager, member of the First Dáil and of the Irish Free State Seanad.

Patrick Beegan was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician.

George Gavan Duffy was an Irish politician, barrister and judge who served as President of the High Court from 1946 to 1951, a Judge of the High Court from 1936 to 1951 and Minister for Foreign Affairs from January 1922 to July 1922. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin County constituency from 1921 to 1923. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Dublin South constituency from 1918 to 1921.

The Irish Republican Army was a guerrilla army that fought the Irish War of Independence against Britain from 1919 to 1921. It saw itself as the legitimate army of the Irish Republic declared in 1919. The Anglo-Irish Treaty, which ended this conflict, was a compromise which abolished the Irish Republic, but created the self-governing Irish Free State, within the British Empire. The IRA was deeply split over whether to accept the Treaty. Some accepted, whereas some rejected not only the Treaty but also the civilian authorities who had accepted it. This attitude eventually led to the outbreak of the Irish Civil War in late June 1922 between pro- and anti-Treaty factions.

Irish republican legitimism denies the legitimacy of the political entities of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland and posits that the pre-partition Irish Republic continues to exist. It is a more extreme form of Irish republicanism, which denotes rejection of all British rule in Ireland. The concept shapes aspects of, but is not synonymous with, abstentionism.

Mary MacSwiney was an Irish republican activist and politician, as well as a teacher. MacSwiney was thrust into both the national and international spotlight in 1920 when her brother Terence MacSwiney, then the Lord Mayor of Cork, went on hunger strike in protest of British policy in Ireland. Mary, alongside her sister-in-law Muriel MacSwiney kept daily vigil over Terence and effectively became spokespeople for the campaign. Terence MacSwiney would ultimately die in October 1920, and from then on Mary MacSwiney acted as an unofficial custodian of his legacy, becoming a dogged and zealous advocate of Irish Republicanism. Following a high-profile seven-month tour of the United States in 1921 in which she and Muriel raised the profile of the Irish independence movement, Mary was elected to Dáil Éireann amidst the ongoing Irish War of Independence. During debates of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, a proposed peace deal between the British and the Irish, MacSwiney was amongst the most outspoken advocates against it. During the ensuing Irish Civil War, MacSwiney supported the Anti-Treaty IRA and was imprisoned for it, resulting in her partaking in two hunger strikes herself.

Michael Patrick Colivet was an Irish Sinn Féin politician. He was Commander of the Irish Volunteers in Limerick during the 1916 Easter Rising, and was elected to the First Dáil.

Catherine Connolly is an Irish independent politician who has been serving as the Leas-Cheann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann since July 2020. She has been a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Galway West constituency since 2016. She previously served as Chair of the Committee on the Irish Language, the Gaeltacht and the Islands from 2016 to 2020 and Mayor of Galway from 2004 to 2005.

The Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013 was an Act of the Oireachtas which, until 2018, defined the circumstances and processes within which abortion in Ireland could be legally performed. The act gave effect in statutory law to the terms of the Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court in the 1992 judgment in the X Case. That judgment allowed for abortion where pregnancy endangers a woman's life, including through a risk of suicide. The provisions relating to suicide had been the most contentious part of the bill. Having passed both Houses of the Oireachtas in July 2013, it was signed into law on 30 July by Michael D. Higgins, the President of Ireland, and commenced on 1 January 2014. The 2013 Act was repealed by the Health Act 2018, which commenced on 1 January 2019.