Charles Keck was an American sculptor from New York City, New York.

Adolph Alexander Weinman was a German-born American sculptor and architectural sculptor.

Paul Philippe Cret was a French-born Philadelphia architect and industrial designer. For more than thirty years, he taught at a design studio in the Department of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

Benjamin Franklin Parkway, commonly abbreviated to Ben Franklin Parkway and colloquially called the Parkway, is a boulevard that runs through the cultural heart of Philadelphia. Named for Benjamin Franklin, a Founding Father, the mile-long Parkway cuts diagonally across the grid plan pattern of Center City's northwest quadrant. It starts at Philadelphia City Hall, curves around Logan Circle, and ends before the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Randolph Rogers was an American Neoclassical sculptor. An expatriate who lived most of his life in Italy, his works ranged from popular subjects to major commissions, including the Columbus Doors at the U.S. Capitol and American Civil War monuments.

Hermon Atkins MacNeil was an American sculptor born in Everett, Massachusetts. He is known for designing the Standing Liberty quarter, struck by the Mint from 1916-1930; and for sculpting Justice, the Guardian of Liberty on the east pediment of the United States Supreme Court building.

Philadelphia National Cemetery is a United States National Cemetery located in the West Oak Lane neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was established in 1862 as nine leased lots in seven private cemeteries in the Philadelphia region. In 1881, the current location was established and the graves of soldiers were reinterred from the various leased lots. It is administered by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, and managed from offices at Washington Crossing National Cemetery. It is 13 acres in size and contains 13,202 burials.

Walker Kirtland Hancock was an American sculptor and teacher. He created notable monumental sculptures, including the Pennsylvania Railroad World War II Memorial (1950–52) at 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, and the World War I Soldiers' Memorial (1936–38) in St. Louis, Missouri. He made major additions to the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., including Christ in Majesty (1972), the bas relief over the High Altar. Works by him are presently housed at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, the Library of Congress, the U.S. Supreme Court, and the United States Capitol.

Eakins Oval is a traffic circle in Philadelphia. It forms the northwest end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway just in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, with a central array of fountains and monuments, and a network of pedestrian walkways.

John Massey Rhind was a Scottish-American sculptor. Among Rhind's better known works is the marble statue of Dr. Crawford W. Long located in the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington D.C. (1926).

During the American Civil War, Philadelphia was an important source of troops, money, weapons, medical care, and supplies for the Union.

The Civil War Memorial is a marble monument situated in the center of Memorial Park in Adrian, Michigan. The monument was designated as a Michigan Historic Site on August 13, 1971 and later added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 29, 1972. It was unveiled on July 4, 1870 to commemorate soldiers from Adrian who died in the American Civil War (1861–1865).

Jakob Otto Schweizer was a Swiss-American sculptor noted for his work on war memorials.

The Stephenson Grand Army of the Republic Memorial, also known as Dr. Benjamin F. Stephenson, is a public artwork in Washington, D.C. honoring Dr. Benjamin F. Stephenson, founder of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization for Union veterans. The memorial is sited at Indiana Plaza, located at the intersection of 7th Street, Indiana Avenue, and Pennsylvania Avenue NW in the Penn Quarter neighborhood. The bronze figures were sculpted by J. Massey Rhind, a prominent 20th-century artist. Attendees at the 1909 dedication ceremony included President William Howard Taft, Senator William Warner, and hundreds of Union veterans.

Lincoln Monument (Philadelphia) is a monument honoring Abraham Lincoln in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of the first initiated in memory of the assassinated president, the monument was designed by neoclassical sculptor Randolph Rogers and completed in 1871. It is now located northeast of the intersection of Kelly Drive and Sedgley Drive, opposite Boathouse Row.

Edward Ludwig Albert Pausch was a Danish-American sculptor noted for his war memorials.

A statue of Frederick Douglass sculpted by Sidney W. Edwards, sometimes called the Frederick Douglass Monument, was installed in Rochester, New York in 1899 after it was commissioned by the African-American activist John W. Thompson. According to Visualising Slavery: Art Across the African Diaspora, it was the first statue in the United States that memorialized a specific African-American person.

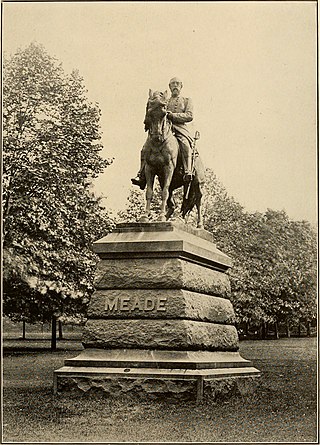

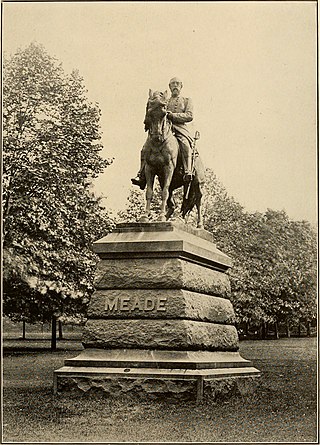

Major General George Gordon Meade is an equestrian statue that stands in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park. The statue, which was unveiled in 1887, was designed by sculptor Alexander Milne Calder and honors George Meade, who had served as an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War and was later a commissioner for the park. The statue is one of two statues of Meade at Fairmount, with the other one being a part of the Smith Memorial Arch.

Samuel Beecher Hart was a state legislator in Pennsylvania. He served multiple terms.