Triple oppression, also called double jeopardy, Jane Crow, or triple exploitation, is a theory developed by black socialists in the United States, such as Claudia Jones. The theory states that a connection exists between various types of oppression, specifically classism, racism, and sexism. It hypothesizes that all three types of oppression need to be overcome at once.

Identity politics is politics based on a particular identity, such as race, nationality, religion, gender, sexual orientation, social background, social class. Depending on which definition of identity politics is assumed, the term could also encompass other social phenomena which are not commonly understood as exemplifying identity politics, such as governmental migration policy that regulates mobility based on identities, or far-right nationalist agendas of exclusion of national or ethnic others. For this reason, Kurzwelly, Pérez and Spiegel, who discuss several possible definitions of the term, argue that it is an analytically imprecise concept.

Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical, fictional, or philosophical discourse. It aims to understand the nature of gender inequality. It examines women's and men's social roles, experiences, interests, chores, and feminist politics in a variety of fields, such as anthropology and sociology, communication, media studies, psychoanalysis, political theory, home economics, literature, education, and philosophy.

Feminist legal theory, also known as feminist jurisprudence, is based on the belief that the law has been fundamental in women's historical subordination. Feminist jurisprudence the philosophy of law is based on the political, economic, and social inequality of the sexes and feminist legal theory is the encompassment of law and theory connected.The project of feminist legal theory is twofold. First, feminist jurisprudence seeks to explain ways in which the law played a role in women's former subordinate status. Feminist legal theory was directly created to recognize and combat the legal system built primarily by the and for male intentions, often forgetting important components and experiences women and marginalized communities face. The law perpetuates a male valued system at the expense of female values. Through making sure all people have access to participate in legal systems as professionals to combating cases in constitutional and discriminatory law, feminist legal theory is utilized for it all.

The matrix of domination or matrix of oppression is a sociological paradigm that explains issues of oppression that deal with race, class, and gender, which, though recognized as different social classifications, are all interconnected. Other forms of classification, such as sexual orientation, religion, or age, apply to this theory as well. Patricia Hill Collins is credited with introducing the theory in her work entitled Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. As the term implies, there are many different ways one might experience domination, facing many different challenges in which one obstacle, such as race, may overlap with other sociological features. Characteristics such as race, age, and sex, may intersectionally affect an individual in extremely different ways, in such simple cases as varying geography, socioeconomic status, or simply throughout time. Other scholars such as Kimberlé Crenshaw's Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color are credited with expanding Collins' work. The matrix of domination is a way for people to acknowledge their privileges in society. How one is able to interact, what social groups one is in, and the networks one establishes is all based on different interconnected classifications.

Feminist sociology is an interdisciplinary exploration of gender and power throughout society. Here, it uses conflict theory and theoretical perspectives to observe gender in its relation to power, both at the level of face-to-face interaction and reflexivity within social structures at large. Focuses include sexual orientation, race, economic status, and nationality.

Intersectionality is an analytical framework for understanding how individuals' various social and political identities result in unique combinations of discrimination and privilege. Intersectionality identifies multiple factors of advantage and disadvantage. Examples of these factors include gender, caste, sex, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, religion, disability, weight, and physical appearance. These intersecting and overlapping social identities may be both empowering and oppressing. However, little good-quality quantitative research has been done to support or undermine the theory of intersectionality.

Lorraine Bethel is an African-American lesbian feminist poet and author.

Black feminism, also known as Afro-feminism chiefly outside the United States, is a branch of feminism that focuses on the African-American woman's experiences and recognizes the intersectionality of racism and sexism. Black feminism also acknowledges the additional marginalization faced by black women due to their social identity.

Barbara Smith is an American lesbian feminist and socialist who has played a significant role in Black feminism in the United States. Since the early 1970s, she has been active as a scholar, activist, critic, lecturer, author, and publisher of Black feminist thought. She has also taught at numerous colleges and universities for 25 years. Smith's essays, reviews, articles, short stories and literary criticism have appeared in a range of publications, including The New York Times Book Review, The Black Scholar, Ms., Gay Community News, The Guardian, The Village Voice, Conditions and The Nation. She has a twin sister, Beverly Smith, who is also a lesbian feminist activist and writer.

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw is an American civil rights advocate and a leading scholar of using critical race theory as a lens to further explore and examine the Tulsa massacre. She is a professor at the UCLA School of Law and Columbia Law School, where she specializes in race and gender issues.

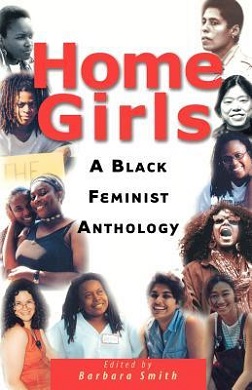

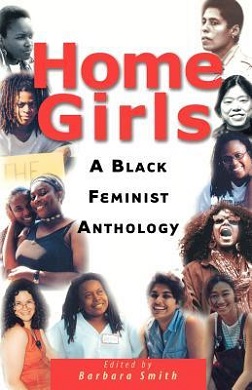

Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (1983) is a collection of Black lesbian and Black feminist essays, edited by Barbara Smith. The anthology includes different accounts from 32 black women of feminist ideology who come from a variety of different areas, cultures, and classes. This collection of writings is intended to showcase the similarities among black women from different walks of life. In the introduction, Smith states her belief that "Black feminism is, on every level, organic to Black experience." Writings within Home Girls support this belief through essays that exemplify black women's struggles and lived experiences within their race, gender, sexual orientation, culture, and home life. Topics and stories discussed in the writings often touch on subjects that in the past have been deemed taboo, provocative, and profound.

Beverly Smith in Cleveland, Ohio, is a Black feminist health advocate, writer, academic, theorist and activist who is also the twin sister of writer, publisher, activist and academic Barbara Smith. Beverly Smith is an instructor of Women's Health at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

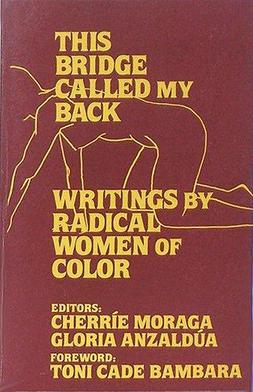

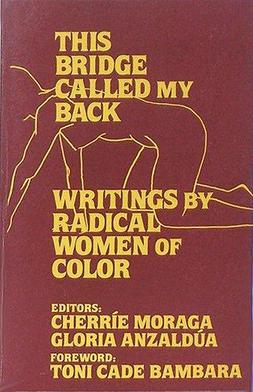

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color is a feminist anthology edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa, first published in 1981 by Persephone Press. The second edition was published in 1983 by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. The book's third edition was published by Third Woman Press until 2008, when it went out of print. In 2015, the fourth edition was published by State University of New York Press, Albany.

Akasha Gloria Hull is an American poet, educator, writer, and critic whose work in African-American literature and as a Black feminist activist has helped shape Women's Studies. As one of the architects of Black Women's Studies, her scholarship and activism has increased the prestige, legitimacy, respect, and popularity of feminism and African-American studies.

The African American Policy Forum (AAPF) is a social justice think tank focused on issues of gender and diversity. AAPF seeks to build bridges between arts, activism, and the academy in order to address structural inequality and systemic oppression. AAPF develops and promotes frameworks and strategies that address a vision of racial justice that embraces the intersections of race, gender, class, and the array of barriers that disempower those who are marginalized in society.

Intersectionality is the interconnection of race, class, and gender among an individual or group. This is often related to an experience of discrimination or a disadvantage. This definition came from Kimberlé Crenshaw. Kimberlé Crenshaw, a feminist scholar, is widely known for coining the term intersection in her 1989 essay, which sheds light on the oppression black women have been exposed to, especially during the slavery period. Crenshaw's analogy of intersection to traffic flow explains, "Discrimination, like traffic through an intersection, may flow in one direction, and it may flow in another. If an accident happens in an intersection, it can be caused by cars traveling from any number of directions and, sometimes, from all of them. Similarly, if a Black woman is harmed because she is in the intersection, her injury could result from sex discrimination or race discrimination."

White feminism is a term which is used to describe expressions of feminism which are perceived as focusing on white women but are perceived as failing to address the existence of distinct forms of oppression faced by ethnic minority women and women lacking other privileges. The term has been used to label and criticize theories that are perceived as focusing solely on gender-based inequality. Primarily used as a derogatory label, "white feminism" is typically used to reproach a perceived failure to acknowledge and integrate the intersection of other identity attributes into a broader movement which struggles for equality on more than one front. In white feminism, the oppression of women is analyzed through a single-axis framework, consequently erasing the identity and experiences of ethnic minority women the space. The term has also been used to refer to feminist theories perceived to focus more specifically on the experience of white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied women, and in which the experiences of women without these characteristics are excluded or marginalized. This criticism has predominantly been leveled against the first waves of feminism which were seen as centered around the empowerment of white middle-class women in Western societies.

Queer of color critique is an intersectional framework, grounded in Black feminism, that challenges the single-issue approach to queer theory by analyzing how power dynamics associated race, class, gender expression, sexuality, ability, culture and nationality influence the lived experiences of individuals and groups that hold one or more of these identities. Incorporating the scholarship and writings of Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Barbara Smith, Cathy Cohen, Brittney Cooper and Charlene A. Carruthers, the queer of color critique asks: what is queer about queer theory if we are analyzing sexuality as if it is removed from other identities? The queer of color critique expands queer politics and challenges queer activists to move out of a "single oppression framework" and incorporate the work and perspectives of differently marginalized identities into their politics, practices and organizations. The Combahee River Collective Statement clearly articulates the intersecting forces of power: "The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives." Queer of color critique demands that an intersectional lens be applied queer politics and illustrates the limitations and contradictions of queer theory without it. Exercised by activists, organizers, intellectuals, care workers and community members alike, the queer of color critique imagines and builds a world in which all people can thrive as their most authentic selves- without sacrificing any part of their identity.

Abolitionist teaching, also known as abolitionist pedagogy, is a set of practices and approaches to teaching that focus on restoring humanity and pursuing educational freedom for all children in schools. It is rooted in Black critical theory. The term was coined by author and professor Bettina Love.