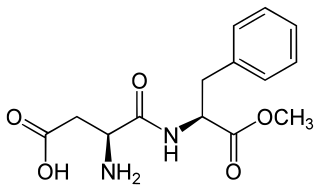

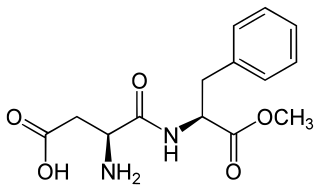

Aspartame is an artificial non-saccharide sweetener 200 times sweeter than sucrose and is commonly used as a sugar substitute in foods and beverages. It is a methyl ester of the aspartic acid/phenylalanine dipeptide with brand names NutraSweet, Equal, and Canderel. Aspartame was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1974, and then again in 1981, after approval was revoked in 1980.

Stevia is a sweet sugar substitute extracted from the leaves of the plant species Stevia rebaudiana native to Paraguay and Brazil.

Sucralose is an artificial sweetener and sugar substitute. As the majority of ingested sucralose is not metabolized by the body, it adds no calories. In the European Union, it is also known under the E number E955. It is produced by chlorination of sucrose, selectively replacing three of the hydroxy groups—in the C1 and C6 positions of the fructose portion and the C4 position of the glucose portion—to give a 1,6-dichloro-1,6-dideoxyfructose–4-chloro-4-deoxygalactose disaccharide. Sucralose is about 600 times sweeter than sucrose, three times as sweet as both aspartame and acesulfame potassium, and twice as sweet as sodium saccharin.

Splenda is a global brand of sugar substitutes and reduced-calorie food products. While the company is known for its original formulation containing sucralose, it also manufactures items using natural sweeteners such as stevia, monk fruit and allulose. It is owned by the American company Heartland Food Products Group. The high-intensity sweetener ingredient sucralose used in Splenda Original is manufactured by the British company Tate & Lyle.

Daminozide, also known as aminozide, Alar, Kylar, SADH, B-995, B-nine, and DMASA, is a plant growth regulator. It was produced in the U.S. by the Uniroyal Chemical Company, Inc,, which registered daminozide for use on fruits intended for human consumption in 1963. In addition to apples and ornamental plants, they also registered it for use on cherries, peaches, pears, Concord grapes, tomato transplants, and peanut vines. Alar was first approved for use in the U.S. in 1963. It was primarily used on apples until 1989, when the manufacturer voluntarily withdrew it after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed banning it based on concerns about cancer risks to consumers.

A sugar substitute is a food additive that provides a sweetness like that of sugar while containing significantly less food energy than sugar-based sweeteners, making it a zero-calorie or low-calorie sweetener. Artificial sweeteners may be derived through manufacturing of plant extracts or processed by chemical synthesis. Sugar substitute products are commercially available in various forms, such as small pills, powders, and packets.

Food energy is chemical energy that animals derive from their food to sustain their metabolism, including their muscular activity.

Acesulfame potassium, also known as acesulfame K or Ace K, is a synthetic calorie-free sugar substitute often marketed under the trade names Sunett and Sweet One. In the European Union, it is known under the E number E950. It was discovered accidentally in 1967 by German chemist Karl Clauss at Hoechst AG. In chemical structure, acesulfame potassium is the potassium salt of 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide. It is a white crystalline powder with molecular formula C

4H

4KNO

4S and a molecular weight of 201.24 g/mol.

Phthalates, or phthalate esters, are esters of phthalic acid. They are mainly used as plasticizers, i.e., substances added to plastics to increase their flexibility, transparency, durability, and longevity. They are used primarily to soften polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Note that while phthalates are usually plasticizers, not all plasticizers are phthalates. The two terms are specific and unique and cannot be used interchangeably.

Diet or light beverages are generally sugar-free, artificially sweetened beverages with few or no calories. They are marketed for diabetics and other people who want to reduce their sugar and/or caloric intake.

Tagatose is a hexose monosaccharide. It is found in small quantities in a variety of foods, and has attracted attention as an alternative sweetener. It is often found in dairy products, because it is formed when milk is heated. It is similar in texture and appearance to sucrose :215 and is 92% as sweet,:198 but with only 38% of the calories.:209 Tagatose is generally recognized as safe by the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization, and has been since 2001. Since it is metabolized differently from sucrose, tagatose has a minimal effect on blood glucose and insulin levels. Tagatose is also approved as a tooth-friendly ingredient for dental products. Consumption of more than about 30 grams of tagatose in a dose may cause gastric disturbance in some people, as it is mostly processed in the large intestine, similar to soluble fiber.:214

David Steinman is an environmentalist, journalist, consumer health advocate, publisher and author. He has published five books focusing largely on environmental, dietary, and consumer safety issues, including Diet for a Poisoned Planet in 1990. He is the founder of the publishing company, Freedom Press, which publishes Healthy Living Magazine, and he also operated an online radio show entitled, Green Patriot Radio.

The artificial sweetener aspartame has been the subject of several controversies since its initial approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1974. The FDA approval of aspartame was highly contested, beginning with suspicions of its involvement in brain cancer, alleging that the quality of the initial research supporting its safety was inadequate and flawed, and that conflicts of interest marred the 1981 approval of aspartame, previously evaluated by two FDA panels that concluded to keep the approval on hold before further investigation. In 1987, the U.S. Government Accountability Office concluded that the food additive approval process had been followed properly for aspartame. The irregularities fueled a conspiracy theory, which the "Nancy Markle" email hoax circulated, along with claims—counter to the weight of medical evidence—that numerous health conditions are caused by the consumption of aspartame in normal doses.

The Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR), based in Washington, D.C., assesses and reviews the safety of ingredients in cosmetics and publishes the results in peer-reviewed scientific literature. The company was established in 1976 by the Personal Care Products Council, with support of the Food and Drug Administration and the Consumer Federation of America.

Nutritional rating systems are used to communicate the nutritional value of food in a more-simplified manner, with a ranking, than nutrition facts labels. A system may be targeted at a specific audience. Rating systems have been developed by governments, non-profit organizations, private institutions, and companies. Common methods include point systems to rank foods based on general nutritional value or ratings for specific food attributes, such as cholesterol content. Graphics and symbols may be used to communicate the nutritional values to the target audience.

The Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, commonly referred to as OEHHA, is a specialized department within the cabinet-level California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA) with responsibility for evaluating health risks from environmental chemical contaminants.

Added sugars or free sugars are sugar carbohydrates added to food and beverages at some point before their consumption. These include added carbohydrates, and more broadly, sugars naturally present in honey, syrup, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates. They can take multiple chemical forms, including sucrose, glucose (dextrose), and fructose.

Elizabeth M. Whelan was an American epidemiologist best known for promoting science that was favorable to industry and for challenging government regulations of consumer products, food, and pharmaceuticals industries that arose from what she said was "junk science." In 1978, she founded the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH) to provide a formal foundation for her work. She also wrote, or co-wrote, more than 20 books and over 300 articles in scientific journals and lay publications.

Fredrick John Stare was an American nutritionist regarded as one of the country's most influential teachers of nutrition.

Sugar is heavily marketed both by sugar producers and the producers of sugary drinks and foods. Apart from direct marketing methods such as messaging on packaging, television ads, advergames, and product placement in setting like blogs, industry has worked to steer coverage of sugar-related health information in popular media, including news media and social media.