The United States Navy Nurse Corps was officially established by Congress in 1908; however, unofficially, women had been working as nurses aboard Navy ships and in Navy hospitals for nearly 100 years. The Corps was all-female until 1965.

Edith Rogers was an American social welfare volunteer and politician who served as a Republican in the United States Congress. She was the first woman elected to Congress from Massachusetts. Until 2012, she was the longest serving Congresswoman and was the longest serving female Representative until 2018. In her 35 years in the House of Representatives she was a powerful voice for veterans and sponsored seminal legislation, including the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, which provided educational and financial benefits for veterans returning home from World War II, the 1942 bill that created the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), and the 1943 bill that created the Women's Army Corps (WAC). She was also instrumental in bringing federal appropriations to her constituency, Massachusetts's 5th congressional district.

Women have been serving in the military since the inception of organized warfare, in both combat and non-combat roles. Their inclusion in combat missions has increased in recent decades, often serving as pilots, mechanics, and infantry officers.

This is a brief account of some the Puerto Rican women who have participated in military actions as members of either a political revolutionary movement or of the Armed Forces of the United States.

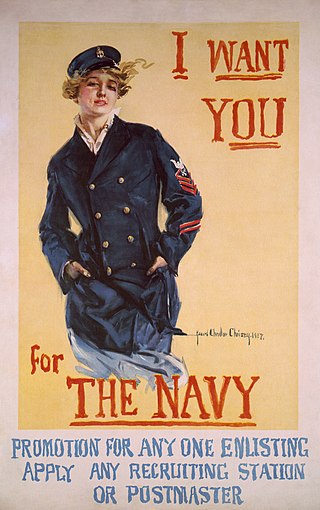

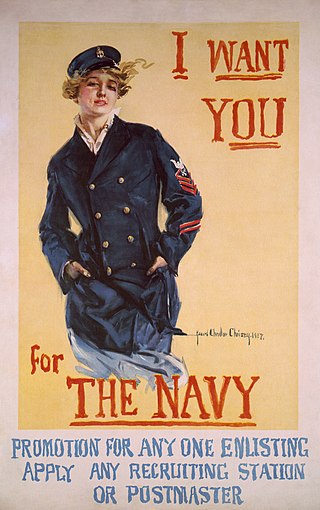

Loretta Perfectus Walsh was the first American woman to officially serve in the United States Armed Forces in a non-nursing capacity. She joined the United States Naval Reserve on March 17, 1917, and subsequently became the first female petty officer in the Naval Reserve when she was sworn in as Chief Yeoman on March 21, 1917.

Yeoman (F) was an enlisted rate for women in the U.S. Naval Reserve during World War I. The first Yeoman (F) was Loretta Perfectus Walsh. At the time, the women were popularly referred to as "yeomanettes" or even "yeowomen", although the official designation was Yeoman (F).

This timeline of women in warfare and the military (1900–1945) deals with the role of women in the military around the world from 1900 through 1945. The two major events in this time period were World War I and World War II. Please see Women in World War I and Women in World War II for more information.

Women in World War I were mobilized in unprecedented numbers on all sides. The vast majority of these women were drafted into the civilian work force to replace conscripted men or to work in greatly expanded munitions factories. Thousands served in the military in support roles, and in some countries many saw combat as well.

The United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, nearly three years after World War I started. A ceasefire and armistice were declared on November 11, 1918. Before entering the war, the U.S. had remained neutral, though it had been an important supplier to the United Kingdom, France, and the other powers of the Allies of World War I.

Hello Girls was the colloquial name for American female switchboard operators in World War I, formally known as the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit. During World War I, these switchboard operators were sworn into the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Until 1977 they were officially categorized as civilian "contract employees" of the US Army. This corps was formed in 1917 from a call by General John J. Pershing to improve the worsening state of communications on the Western front. Applicants had to be bilingual in English and French to ensure that orders would be heard by anyone. Over 7,000 women applied, but only 450 women were accepted. Many of these women were former switchboard operators or employees at telecommunications companies. They completed their Signal Corps training at Camp Franklin, now a part of Fort George G. Meade in Maryland.

The recent history of changes in women's roles includes having women in the military. Every country in the world permits the participation of women in the military, in one form or another. In 2018, only two countries conscripted women and men on the same formal conditions: Norway and Sweden. A few other countries have laws conscripting women into their armed forces, however with some difference such as service exemptions, length of service, and more. Some countries do not have conscription, but men and women may serve on a voluntary basis under equal conditions. Alenka Ermenc was the first female head of armed forces in any of the NATO member states, having served as the Chief of the General Staff of the Slovenian Armed Forces between 2018 and 2020.

The United States Army Nurse Corps (USANC) was formally established by the U.S. Congress in 1901. It is one of the six medical special branches of officers which – along with medical enlisted soldiers – comprise the Army Medical Department (AMEDD). The ANC is the nursing service for the U.S. Army and provides nursing staff in support of the Department of Defense medical plans. The ANC is composed entirely of Registered Nurses (RNs) and Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRN).

This article is about the role played by women in the military in the Americas, particularly in the United States and Canada from the First World War to modern times.

This is a timeline of women in warfare in the United States from 1900 until 1949.

This is a timeline of women in warfare in the United States up until the end of World War II. It encompasses the colonial era and indigenous peoples, as well as the entire geographical modern United States, even though some of the areas mentioned were not incorporated into the United States during the time periods that they were mentioned.

American women in World War II became involved in many tasks they rarely had before; as the war involved global conflict on an unprecedented scale, the absolute urgency of mobilizing the entire population made the expansion of the role of women inevitable. Their services were recruited through a variety of methods, including posters and other print advertising, as well as popular songs. Among the most iconic images were those depicting "Rosie the Riveter", a woman factory laborer performing what was previously considered man's work.

There have been women in the United States Army since the Revolutionary War, and women continue to serve in it today. As of 2020, there were 74,592 total women on active duty in the US Army, with 16,987 serving as officers and 57,605 enlisted. While the Army has the highest number of total active duty members, the ratio of women-men is lower than the US Air Force and the US Navy, with women making up 15.5% of total active duty Army in 2020.

There have been women in the United States Marine Corps since 1918, and women continue to serve in the Corps today.

This article lists events involving Women in warfare and the military in the United States since 2011. For the previous decade, see Timeline of women in warfare and the military in the United States, 2000–2010.