Amerigo Vespucci was an Italian merchant, explorer, and navigator from the Republic of Florence, from whose name the term "America" is derived.

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator who completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean, opening the way for European exploration and colonization of the Americas. His expeditions, sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, were the first European contact with the Caribbean, Central America, and South America.

Martin Waldseemüller was a German cartographer and humanist scholar. Sometimes known by the Latinized form of his name, Hylacomylus, his work was influential among contemporary cartographers. He and his collaborator, Matthias Ringmann, are credited with the first recorded usage of the word America to name a portion of the New World in honour of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci. Waldseemüller was also the first to map South America as a continent separate from Asia; the first to produce a printed globe and the first to create a printed wall map of Europe. A set of his maps printed as an appendix to the 1513 edition of Ptolemy's Geography is considered to be the first example of a modern atlas.

Portugal was a leading country in the European exploration of the world in the 15th century. The Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 divided the Earth outside Europe into Castilian and Portuguese global territorial hemispheres for exclusive conquest and colonization. Portugal colonized parts of South America, but also made some unsuccessful attempts to colonize North America.

Giovanni da Verrazzano was a Florentine explorer of North America, in the service of King Francis I of France.

Richard ap Meryk, anglicised to Richard Amerike was an Anglo-Welsh merchant, royal customs officer and, at the end of his life, sheriff of Bristol. Several claims have been made for Amerike by popular writers of the late twentieth century. One was that he was the major funder of the voyage of exploration launched from Bristol by the Venetian John Cabot in 1497, and that Amerike was the owner of Cabot's ship, the Matthew. The other claim revived a theory first proposed in 1908 by a Bristolian scholar and amateur historian, Alfred Hudd. Hudd's theory, greatly elaborated by later writers, suggested that the continental name America was derived from Amerike's surname in gratitude for his sponsorship of Cabot's successful discovery expedition to the 'New World'. However, neither claim is backed up by hard evidence, and the consensus view is that America is named after Amerigo Vespucci, the Italian explorer.

The naming of the Americas, or America, occurred shortly after Christopher Columbus' voyage to the Americas in 1492. It is generally accepted that the name derives from Amerigo Vespucci, the Italian explorer, who explored the new continents in the following years. However, some have suggested other explanations, including being named after a mountain range in Nicaragua, or after Richard Amerike of Bristol.

The Age of Discovery, or the Age of Exploration, is an informal and loosely defined term for the period in European history in which extensive overseas exploration, led by the Portuguese, emerged as a powerful factor in European culture, most notably the European rediscovery of the Americas. It also marks an increased adoption of colonialism as a national policy in Europe. Several lands previously unknown to Europeans were discovered by them during this period, though most were already inhabited.

Juan Díaz de Solís was a 16th-century navigator and explorer. He is also said to be the first European to land on what is now modern day Uruguay.

Alonso de Ojeda was a Spanish explorer, governor and conquistador. He travelled through Guyana, Venezuela, Trinidad, Tobago, Curaçao, Aruba and Colombia. He navigated with Amerigo Vespucci who is famous for having named Venezuela, which he explored during his first two expeditions, for having been the first European to visit Guyana, Curaçao, Colombia, and Lake Maracaibo, and later for founding Santa Cruz.

The Casa de Contratación or Casa de la Contratación de las Indias was established by the Crown of Castile, in 1503 in the port of Seville as a crown agency for the Spanish Empire. It functioned until 1790, when it was abolished in a government reorganization. Before the establishment of the Council of the Indies in 1524, the Casa de Contratación had broad powers over overseas matters, especially financial matters concerning trade and legal disputes arising from it. It also was responsible for the licensing of emigrants, training of pilots, creation of maps and charters, probate of estates of Spaniards dying overseas. Its official name was La Casa y Audiencia de Indias.

Matthias Ringmann (1482–1511), also known as Philesius Vogesigena, was an Alsatian German humanist scholar, cosmographer, and poet. Along with cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, he is credited with the first documented usage of the word America, on the 1507 map Universalis Cosmographia in honour of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci.

Gonçalo Coelho was a Portuguese explorer who belonged to a prominent family in northern Portugal. He commanded two expeditions which explored much of the coast of Brazil.

The term "New World" is a name used for the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas. The term gained prominence in the early 16th century, during the Age of Discovery, shortly after Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci concluded that America represented a new continent, and subsequently published his findings in a pamphlet titled Mundus Novus. This realization expanded the geographical horizon of classical European geographers, who had thought the world consisted of Africa, Europe, and Asia, collectively now referred to as the Old World, or Afro-Eurasia. The Americas were also referred to as the fourth part of the world.

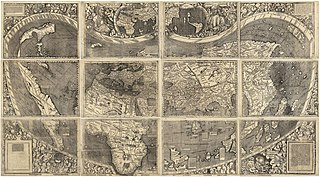

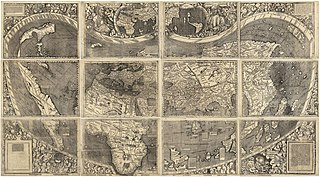

The Waldseemüller map or Universalis Cosmographia is a printed wall map of the world by German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, originally published in April 1507. It is known as the first map to use the name "America". The name America is placed on what is now called South America on the main map. As explained in Cosmographiae Introductio, the name was bestowed in honor of the Italian Amerigo Vespucci.

Between 1492 and 1504, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus led four Spanish-based transatlantic maritime expeditions to the Americas, a continental landmass which was virtually unknown to and outside of the Old World (Afro-Eurasia). These voyages to America led to the widespread knowledge of its existence. This breakthrough inaugurated the period known as the Age of Discovery, which saw the colonization of the Americas, a related biological exchange, and trans-Atlantic trade. These events, the effects and consequences of which persist to the present, are sometimes cited as the beginning of the modern era.

Martín Fernández de Enciso was a navigator and geographer from Seville, Spain. He was instrumental in colonising the Isthmus of Darien. Fernandez de Enciso founded a village near the Cabo de la Vela with the name Nuestra Señora Santa María de los Remedios del Cabo de la Vela, the first settlement in the Guajira Peninsula. Due to constant attacks from the indigenous and pirates the village was moved to present-day Riohacha in 1544. His Suma de Geografia que trata de todas las partidas e provincias del mundo, published in 1519 in Seville, was the first account in the Spanish language of the discoveries of the New World. Among other things, this document contains one of the first western descriptions of the avocado.

John Cabot was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest known European exploration of coastal North America since the Norse visits to Vinland in the eleventh century. To mark the celebration of the 500th anniversary of Cabot's expedition, both the Canadian and British governments elected Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland, as representing Cabot's first landing site. However, alternative locations have also been proposed.

The Virgin of the Navigators is a painting by Spanish artist Alejo Fernández, created as the central panel of an altarpiece for the chapel of the Casa de Contratación in Alcázar of Seville, Seville, southern Spain. It was probably painted sometime between 1531 and 1536. Carla Rahn Phillips has suggested that it represents Christopher Columbus as a European magus-king reinforcing "the notion that the Spanish Empire represented the fulfillment of biblical prophecy to bring the Christian message to all the peoples of the world.

The exploration of North America by non-indigenous people was a continuing effort to map and explore the continent and advance the economic interests of said non-indigenous peoples of North America. It spanned centuries, and consisted of efforts by numerous people and expeditions from various foreign countries to map the continent. See also the European colonization of the Americas