Related Research Articles

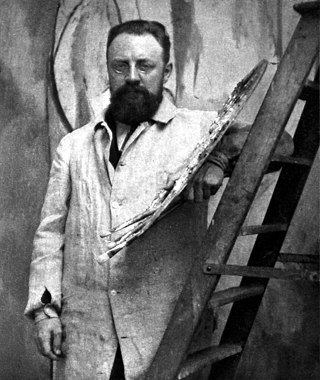

Henri Émile Benoît Matisse was a French visual artist, known for both his use of colour and his fluid and original draughtsmanship. He was a draughtsman, printmaker, and sculptor, but is known primarily as a painter. Matisse is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso, as one of the artists who best helped to define the revolutionary developments in the visual arts throughout the opening decades of the twentieth century, responsible for significant developments in painting and sculpture.

Tess Jaray is a British painter and printmaker. She taught at The Slade School of Fine Art, UCL from 1968 until 1999. Over the last twenty years Jaray has completed a succession of major public art projects. She was made an Honorary Fellow of RIBA in 1995 and a Royal Academician in 2010.

Morgan Russell was a modern American artist. With Stanton Macdonald-Wright, he was the founder of Synchromism, a provocative style of abstract painting that dates from 1912 to the 1920s. Russell's "synchromies," which analogized color to music, were an early American contribution to the rise of Modernism.

Rosalind Epstein Krauss is an American art critic, art theorist and a professor at Columbia University in New York City. Krauss is known for her scholarship in 20th-century painting, sculpture and photography. As a critic and theorist she has published steadily since 1965 in Artforum,Art International and Art in America. She was associate editor of Artforum from 1971 to 1974 and has been editor of October, a journal of contemporary arts criticism and theory that she co-founded in 1976.

Joan Mitchell was an American artist who worked primarily in painting and printmaking, and also used pastel and made other works on paper. She was an active participant in the New York School of artists in the 1950s. A native of Chicago, she is associated with the American abstract expressionist movement, even though she lived in France for much of her career.

Sigrid Hjertén was a Swedish modernist painter. Hjertén is considered a major figure in Swedish modernism. Periodically she was highly productive and participated in 106 exhibitions. She worked as an artist for 30 years before dying of complications from a lobotomy for schizophrenia.

Henry McBride was an American art critic known for his support of modern artists, both European and American, in the first half of the twentieth century. As a writer during the 1920s for the newspaper The New York Sun and the avant-garde magazine The Dial, McBride became one of the most influential supporters of modern art in his time. He also wrote for Creative Art (1928-1932) and Art News (1950-1959). Living to be ninety-five, McBride was born in the era of Winslow Homer and the Hudson River School and lived to see the rise of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and the New York School.

"Bad" Painting is the name given by critic and curator Marcia Tucker to a trend in American figurative painting in the 1970s. Tucker curated an exhibition of the same name at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, featuring the work of fourteen artists mostly unknown in New York at the time. The exhibition ran from January 14 to February 28, 1978.

Irving Sandler was an American art critic, art historian, and educator. He provided numerous first hand accounts of American art, beginning with abstract expressionism in the 1950s. He also managed the Tanager Gallery downtown and co-ordinated the New York Artists Club of the New York School from 1955 to its demise in 1962 as well as documenting numerous conversations at the Cedar Street Tavern and other art venues. Al Held named him, "Our Boswell of the New York scene," and Frank O'Hara immortalized him as the "balayeur des artistes" because of Sandler's constant presence and habit of taking notes at art world events. Sandler saw himself as an impartial observer of this period, as opposed to polemical advocates such as Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg.

Pattern and Decoration was a United States art movement from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s. The movement has sometimes been referred to as "P&D" or as The New Decorativeness. The movement was championed by the gallery owner Holly Solomon. The movement was the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Hudson River Museum in 2008.

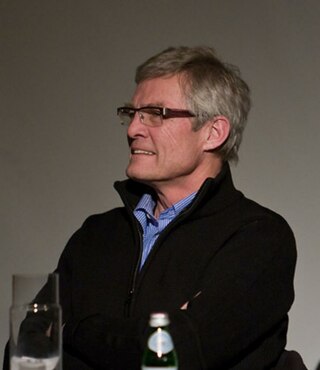

John O'Brian is an art historian, writer, and curator. He is best known for his books on modern art, including Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, one of TheNew York Times "Notable Books of the Year" in 1986, and for his exhibitions on nuclear photography such as Camera Atomica, organized for the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2015. Camera Atomica was the first comprehensive exhibition on postwar nuclear photography. From 1987 to 2017 he taught at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, where he held the Brenda & David McLean Chair in Canadian Studies (2008-11) and was an associate of the Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies. O'Brian has been a critic of neoconservative policies since the start of the Culture Wars in the 1980s. He is a recipient of the Thakore Award in Human Rights and Peace Studies from Simon Fraser University.

Joyce Kozloff is an American artist known for her paintings, murals, and public art installations. She was one of the original members of the Pattern and Decoration movement and an early artist in the 1970s feminist art movement, including as a founding member of the Heresies collective.

Valerie Jaudon is an American painter commonly associated with various Postminimal practices – the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s, site-specific public art, and new tendencies in abstraction.

Robert Kushner(; born 1949, Pasadena, CA) is an American contemporary painter who is known especially for his involvement in Pattern and Decoration. He has been called "a founder" of that artistic movement. In addition to painting, Kushner creates installations in a variety of mediums, from large-scale public mosaics to delicate paintings on antique book pages.

Shirley Kaneda is an abstract painter and artist based in New York City.

Holly Solomon Gallery opened in New York City in 1975 at 392 West Broadway in Soho, Manhattan. Started by Holly Solomon - aspiring actress, style-icon, and collector - and her husband Horace Solomon, the gallery was initially known for launching major art careers and nurturing the artistic movement known as Pattern and Decoration, which was a reaction to the austerities of Minimal art.

Cynthia Carlson is an American visual artist, living and working in New York.

Merion Estes is a Los Angeles-based painter. She earned a B.F.A. at the University of New Mexico, in Albuquerque, and an M.F.A. at the University of Colorado, in Boulder. Estes was raised in San Diego from the age of four. She moved to Los Angeles in 1972 and first showed her work at the Woman's Building in Los Angeles. As a founding member of Grandview 1 & 2, she was involved in the beginnings of Los Angeles feminist art organizations including Womanspace, and the feminist arts group "Double X," along with artists Judy Chicago, Nancy Buchanan, Faith Wilding, and Nancy Youdelman. In 2014, Un-Natural, which was shown at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in Los Angeles and included Estes' work, was named one of the best shows in a non-profit institution in the United States by the International Association of Art Critics.

Susan Michod is an American feminist painter who has been at the forefront of the Pattern and Decoration movement since 1969. Her work "consists of monumental paintings [which are] thickly painted, torn, collaged, spattered, sponged, sprinkled with glitter and infused with a spirit of love of nature and art," the art critic Sue Taylor has written.

Judy Ledgerwood is an American abstract painter and educator, who has been based in Chicago. Her work confronts fundamental, historical and contemporary issues in abstract painting within a largely high-modernist vocabulary that she often complicates and subverts. Ledgerwood stages traditionally feminine-coded elements—cosmetic and décor-related colors, references to ornamental and craft traditions—on a scale associated with so-called "heroic" abstraction; critics suggest her work enacts an upending or "domestication" of modernist male authority that opens the tradition to allusions to female sexuality, design, glamour and pop culture. Critic John Yau writes, "In Ledgerwood’s paintings the viewer encounters elements of humor, instances of surprise, celebrations of female sexuality, forms of vulgar tactility, and intense and unpredictable combinations of color. There is nothing formulaic about her approach."

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kushner, Robert (2011). "Amy Goldin 1926-1978" in Amy Goldin: Art in a Hairshirt. Stockbridge, Massachusetts: Hard Press Editions. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-55595-342-3.

- ↑ http://blackmountaincollegeproject.org/>

- ↑ Goldin, Amy (1960). George Economou; Joan Kelly; Robert Kelly (eds.). Trobar: A Magazine of the New Poetry. Brooklyn: Orion Press.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ↑ Frank, Peter (July 31, 1978). "Review". Village Voice. New York.

- ↑ Barite, Jaqueline (September–October 1965), "Amy Mendelson", Arts Magazine, p. 76

- ↑ Wilson-Powell, MaLin (September 19, 2003). "Worldly art critic's work resurfaces". LA Times. Los Angeles.

- ↑ Goldin, Amy (June 1966), "The Sculpture of George Sugarman", Arts Magazine

- ↑ Swartz, Anne (2007). Pattern and Decoration: An Ideal Vision in American Art, 1975-1985. Yonkers, NY: Hudson River Museum. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-943651-35-4.

- ↑ Zghal, Emna (2011), "The Content of Decoration", in Robert Kushner (ed.), Art in a Hairshirt, Hard Press Editions, pp. 162–165, ISBN 978-1-55595-342-3

- ↑ Knight, Christopher (October 9, 2011). "'Amy Goldin: Art in a Hairshirt' offers insightful essays". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Larry Gross (4 June 2019). On The Margins Of Art Worlds. Taylor & Francis. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-1-00-030715-3.

- ↑ Golden, Amy (May–June 1974), "The Esthetic Ghetto: Some Thoughts about Public Art", Art in America

- ↑ Goldin, Amy (March–April 1978). "Pattern & Print" (PDF). Print Collector's Newsletter.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ Cotter, Holland (2008-01-15), "Scaling a Minimalist Wall With Bright, Shiny Colors", New York Times

- ↑ Goldin, Amy (September 1975), "Patterns, Grids, and Painting", Artforum

- ↑ Goldin, Amy (July–August 1975), "Matisse and Decoration: The Late Cut-Outs", Art in America

- ↑ "With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985 • MOCA". Moca.org. 2019-10-27. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- 1 2 Jaudon, Valerie (Winter 1977–1978), "Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture." (PDF), Heresies #4, retrieved 2012-09-12

- ↑ Stiles, Kristine and Peter Selz (1996). Theories and Document of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings. Berkeley and Los Angeles California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20251-1. pp. 154–155

- ↑ http://www.collegeart.org/awards/matherpast>