Amy Sillman is a New York-based visual artist, known for process-based paintings that move between abstraction and figuration, and engage nontraditional media including animation, zines and installation. Her work draws upon art historical tropes, particularly postwar American gestural painting, as both influences and foils; she engages feminist critiques of the discourses of mastery, genius and power in order to introduce qualities such as humor, awkwardness, self-deprecation, affect and doubt into her practice. Profiles in The New York Times, ARTnews, Frieze, and Interview, characterize Sillman as championing "the relevance of painting" and "a reinvigorated mode of abstraction reclaiming the potency of active brushwork and visible gestures." Critic Phyllis Tuchman described Sillman as "an inventive abstractionist" whose "messy, multivalent, lively" art "reframes long-held notions regarding the look and emotional character of abstraction."

Ronnie Landfield is an American abstract painter. During his early career from the mid-1960s through the 1970s his paintings were associated with Lyrical Abstraction, and he was represented by the David Whitney Gallery and the André Emmerich Gallery.

Lyrical abstraction is either of two related but distinct trends in Post-war Modernist painting:

Ronald "Ron" Davis is an American painter whose work is associated with geometric abstraction, abstract illusionism, lyrical abstraction, hard-edge painting, shaped canvas painting, color field painting, and 3D computer graphics. He is a veteran of nearly seventy solo exhibitions and hundreds of group exhibitions.

Olivier Mosset is a Swiss visual artist. He lives and works in Tucson, Arizona.

Seymour Boardman (1921–2005) was a New York abstract expressionist. Since his first solo exhibition in Paris in 1951, Boardman developed a personal vision and style of his own, following his own path of abstraction. As a painter he sought to reduce the image to its bare essence.

Alvin D. Loving Jr., better known as Al Loving, was an African-American abstract expressionist painter. His work is known for hard-edge abstraction, fabric constructions, and large paper collages, all exploring complicated color relationships.

Carol Diehl is an American artist, art critic and poet. In addition to her writing, most recently appearing in her blog Art Vent, she is best known for her paintings, which have often documented daily life in a manner described as diaristic, even compulsive, using dense, painterly, often indecipherable words, numbers and symbols in grid or geometric frameworks. Diehl has also been a prolific art critic, having contributed features and reviews to numerous periodicals, including Art in America, ARTnews, and Art + Auction, as well as to books and artist catalogues. In the 1990s, she became active in New York's performance poetry scene. Diehl lives in New York City and southwestern Massachusetts. She has two sons, Matt Diehl and Adam Diehl.

Thornton Willis is an American abstract painter. He has contributed to the New York School of painting since the late 1960s. Viewed as a member of the Third Generation of American Abstract Expressionists, his work is associated with Abstract Expressionism, Lyrical Abstraction, Process Art, Postminimalism, Bio-morphic Cubism and Color Field painting.

Candida Alvarez is an American artist and professor, known for her paintings and drawings.

John Zurier is an abstract painter born in Santa Monica, CA, known for his minimal, near-monochrome paintings. His work has shown across the American West as well as in Europe and Japan. He has worked in Reykjavik, Iceland and Berkeley, Ca.

Ralph Humphrey was an American abstract painter whose work has been linked to both Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. He was active in the New York art scene in the 1960s and '70s. His paintings are best summarized as an exploration of space through color and structure. He lived and worked in New York, NY.

Victor George Kord is an American painter and educator. He currently maintains a studio and exhibits in New York City. He previously served as art department chair for several major universities, and remains professor emeritus of painting at Cornell University Department of Art.

Rodney Carswell is an American abstract artist. He first gained recognition for human-scaled, geometric paintings that feature exposed, projected support structures, creating interplay between sculptural presence and richly painted pictorial surfaces. His recent paintings eschew the superstructures and evoke a greater sense of immediacy, playfulness, and narrative. Critics often describe Carswell's work as uncanny, elusive or quirky, for its tendency to negotiate "in-between" spaces and embrace contradictions such as order and instability, intention and accident, or back and front. Employing irregularly shaped canvasses, thick supports, and openings or holes that reveal the stretcher construction and walls behind them, works like 3 (1994) often occupy a place between painting and sculpture. In a similar way, Carswell uses the modernist languages of Minimalism, Suprematism and Constructivism, yet eludes those categories with postmodern allusions to architecture, the body and spiritual iconography, and with his process-oriented, "hand-made" surfaces. In his essay for Carswell's mid-career retrospective at Chicago's Renaissance Society, Los Angeles Times critic David Pagel suggested that his understated paintings worked their way into the one's consciousness in a "supple, somewhat unsettling manner" that achieves a subtle, but lingering shift in perception.

Judith Murray is an American abstract painter based in New York City. Active since the 1970s, she has produced a wide-ranging, independent body of work while strictly adhering to idiosyncratic, self-imposed constants within her practice. Since 1975, she has limited herself to a primary palette of red, yellow, black and white paints—from which she mixes an infinite range of hues—and a near-square, horizontal format offset by a vertical bar painted along the right edge of the canvas; the bar serves as a visual foil for the rest of the work and acknowledges each painting’s boundary and status as an abstract object. Critic Lilly Wei describes Murray's work as "an extended soliloquy on how sensation, sensibility, and digressions can still be conveyed through paint" and how by embracing the factual world the "abstract artist can construct a supreme and sustaining fiction."

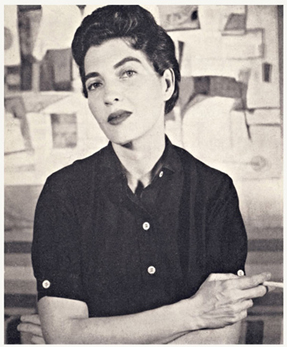

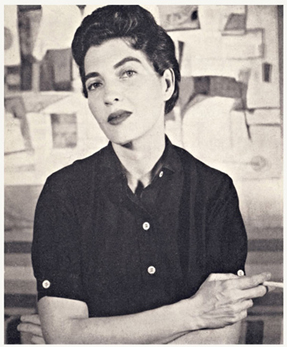

Ethel Fisher was an American painter whose career spanned more than seven decades in New York City, Miami and Los Angeles. Her work ranges across abstraction and representational genres including large-scale portraiture, architectural "portraits," landscape and still-life, and is unified by a sustained formal emphasis on color and space. After studying at the Art Students League in the 1940s, Fisher found success as an abstract artist in Florida in the late 1950s, and began exhibiting her work nationally and in Havana, Cuba. Her formative work of this period embraced the history of art, architecture and anthropology; she referred to it as "abstract impressionist" to distinguish her approach to form and color from that of Abstract Expressionism.

Frances Barth is an American visual artist best known for paintings situated between abstraction, landscape and mapping, and in her later career, video and narrative works. She emerged during a period in which contemporary painters sought a way forward beyond 1960s minimalism and conceptualism, producing work that combined modernist formalism, geometric abstraction, referential elements and metaphor. Critic Karen Wilkin wrote, "Barth’s paintings play a variety of spatial languages against each other, from aerial views that suggest mapping, to suggestions of perspectival space, to relentless flatness … [she] questions the very pictorial conventions she deploys, creating ambiguous imagery and equally ambiguous space that seems to shift as we look."

Woody De Othello is an American ceramicist and painter. He lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area, California.

James Little is an American painter and curator. He is known for his works of geometric abstraction which are often imbued with exuberant color. He has been based in New York City.

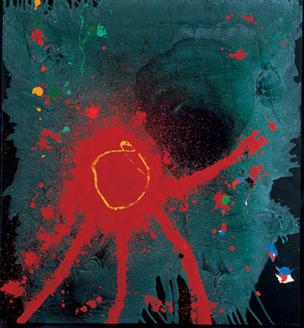

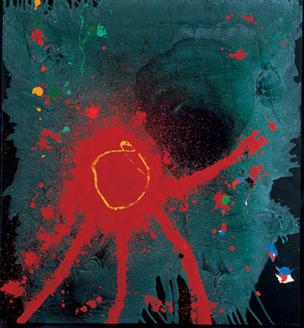

Joan Moment is an American painter based in Northern California. She emerged out of the 1960s Northern California Funk art movement and gained attention when the Whitney Museum of American Art Curator Marcia Tucker selected her for the 1973 Biennial and for a solo exhibition at the Whitney in 1974. Moment is known for process-oriented paintings that employ non-traditional materials and techniques evoking vital energies conveyed through archetypal iconography. Though briefly aligned with Funk—which was often defined by ribald humor and irreverence toward art-world pretensions—her work diverged by the mid-1970s, fusing abstraction and figuration in paintings that writers compared to prehistoric and tribal art. Critic Victoria Dalkey wrote that Moment's methods combined chance and improvisation to address "forces embodied in a universe too large for us to comprehend, as well as the … fragility and transience of the material world."