Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of works authored by rabbis throughout Jewish history. The term typically refers to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writings. It aligns with the Hebrew term Sifrut Chazal, which translates to “literature [of our] sages” and generally pertains only to the sages (Chazal) from the Talmudic period. This more specific sense of "Rabbinic literature"—referring to the Talmud, Midrashim, and related writings, but hardly ever to later texts—is how the term is generally intended when used in contemporary academic writing. The terms mefareshim and parshanim almost always refer to later, post-Talmudic writers of rabbinic glosses on Biblical and Talmudic texts.

Torah study is the study of the Torah, Hebrew Bible, Talmud, responsa, rabbinic literature, and similar works, all of which are Judaism's religious texts. According to Rabbinic Judaism, the study is done for the purpose of the mitzvah ("commandment") of Torah study itself.

Tefillin, or phylacteries, are a set of small black leather boxes with leather straps containing scrolls of parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah. Tefillin are worn by adult Jews during weekday and Sunday morning prayers. In Orthodox and traditional communities, they are worn solely by men, while some Reform and Conservative (Masorti) communities allow them to be worn by either sex. In Jewish law (halacha), women are exempt from most time-dependent positive commandments, which include tefillin, and unlike other time-dependent positive commandments, most halachic authorities prohibit from fulfilling this commandment.

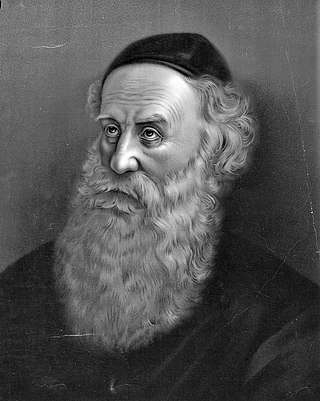

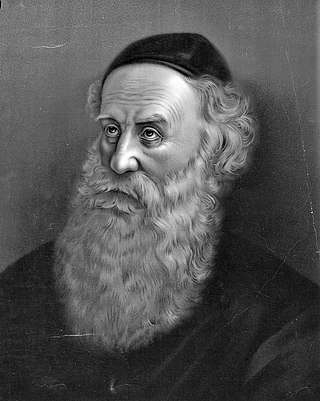

Shneur Zalman of Liadi, commonly known as the Alter Rebbe or Baal Hatanya, was a rabbi as well as the founder and first Rebbe of Chabad, a branch of Hasidic Judaism. He wrote many works, and is best known for Shulchan Aruch HaRav, Tanya, and his Siddur Torah Or compiled according to the Nusach Ari.

In Judaism and Christianity, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is one of two specific trees in the story of the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2–3, along with the tree of life. Alternatively, some scholars have argued that the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is just another name for the tree of life.

The Tanya is an early work of Hasidic philosophy, by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad Hasidism, first published in 1796. Its formal title is Likkutei Amarim, but is more commonly known by its first Hebrew word tanya, which means "it has been taught", where he refers to a baraita section in "Niddah", at the end of chapter 3, 30b. Tanya is composed of five sections that define Hasidic mystical psychology and theology as a handbook for daily spiritual life in Jewish observance.

Breslov is a branch of Hasidic Judaism founded by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov (1772–1810), a great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidism. Its adherents strive to develop an intense, joyous relationship with God, and receive guidance toward this goal from the teachings of Rebbe Nachman.

Tzadik is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d-q, which means "justice" or "righteousness". When applied to a righteous woman, the term is inflected as tzadeket/tzidkaniot.

In the branch of Jewish mysticism known as Kabbalah, Daʻat or Da'ath is the location where all ten sefirot in the Tree of Life are united as one.

Devekut, debekuth, deveikuth or deveikus is a Jewish concept referring to closeness to God. It may refer to a deep, trance-like meditative state attained during Jewish prayer, Torah study, or when performing the 613 commandments. It is particularly associated with the Jewish mystical tradition.

In Judaism, yetzer hara is a term for humankind's congenital inclination to do evil. The term is drawn from the phrase "the inclination of the heart of man is evil", which occurs twice at the beginning of the Torah.

Judaism regards the violation of any of the 613 commandments as a sin. Judaism teaches that to sin is a part of life, since there is no perfect human and everyone has an inclination to do evil "from youth", though people are born sinless. Sin has many classifications and degrees.

The gift of the foreleg, cheeks and maw of a kosher-slaughtered animal to a kohen is a positive commandment in the Hebrew Bible. The Shulchan Aruch rules that after the slaughter of animal by a shochet, the shochet is required to separate the cuts of the foreleg, cheek and maw and give them to a kohen freely, without the kohen paying or performing any service.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Judaism:

Kochos/Kochot haNefesh, meaning "Powers of the Soul", are the innate constituent character-aspects within the soul, in Hasidic thought's psychological internalisation of Kabbalah. They derive from the 10 Sephirot Heavenly emanations of Kabbalah, by relating each quality to its parallel internal motivation in man. The Hasidic discussion of the sephirot, particularly in the Kabbalistically oriented system of Habad thought, focuses principally on the Soul Powers, the experience of the sephirot in Jewish worship.

In kabbalah, the divine soul is the source of good inclination, or yetzer tov, and Godly desires.

Chabad philosophy comprises the teachings of the leaders of Chabad-Lubavitch, a Hasidic movement. Chabad Hasidic philosophy focuses on religious concepts such as God, the soul, and the meaning of the Jewish commandments.

Happiness in Judaism and Jewish thought is considered an important value, especially in the context of the service of God. A number of Jewish teachings stress the importance of joy, and demonstrate methods of attaining happiness.

Anger in Judaism is treated as a negative trait to be avoided whenever possible. The subject of anger is treated in a range of Jewish sources, from the Hebrew Bible and Talmud to the rabbinical law, Kabbalah, Hasidism, and contemporary Jewish sources.