Archibald Cregeen (baptised 20 November 1774 - 9 April 1841) was a Manx lexicographer and scholar. He is best known for compiling A Dictionary of the Manks Language (1838), which was the first dictionary for the Manx language to be published.

Archibald Cregeen (baptised 20 November 1774 - 9 April 1841) was a Manx lexicographer and scholar. He is best known for compiling A Dictionary of the Manks Language (1838), which was the first dictionary for the Manx language to be published.

Archibald Cregeen was born in late October or early November to Manxman William Cregeen and his Irish wife Mary Fairclough in Colby on the Isle of Man. [1] In 1798 he married Jane Crellin, and they had eight children. Shortly after his wedding, he built a small cottage near his father's in Colby and lived there with his family for the rest of his life. [2] Although his father was a cooper by trade, Cregeen became a marble mason, engraving lettering on tombstones. [3]

He was appointed coroner of Rushen Sheading in 1813. [2] This was a position of considerable responsibility and influence in the local community, as the coroner held inquests of deaths, served summonses, and levied fines. [3]

He died on Good Friday on 9 April 1841. He was buried in St Columba, Arbory parish church in Ballabeg. His tomb has an inscription which describes him as having "lived respected and died lamented". [1]

Manx is a member of the Goidelic language family, closely related to Irish and Scottish Gaelic. Cregeen himself was a native Manx speaker, as Manx was the community language for much of the island at that time. The language was first brought to the island by sailors, monks and traders from Ireland as they travelled to and from Britain. The language changed significantly due to the influence of Norse after the Viking invasion of the Isle of Man and its relative political isolation from the rest of the Gaelic speaking world in later centuries.[ citation needed ]

Cregeen was aware of the long and complicated history of the Manx language, describing the language as being "ancient" and "venerable for its antiquity". [4] Despite this, Cregeen noted the negative attitudes towards it and the low-prestige nature of the language on the Isle of Man in the preface to his dictionary:

I am well aware that the utility or the following work will be variously appreciated by my brother Manksmen. Some will be disposed to deride the endeavour to restore vigour to a decaying language. Those who reckon the extirpation of the Manks a necessary step towards that general extension of the English, which they deem essential to the interest of the Isle of Man, will condemn every effort which seems likely to retard its extinction.

Cregeen began work on the dictionary in 1814. He did not work completely alone, but was aided by several Manx clergymen, notably Reverend John Edward Harrison, a vicar of the parish of Jurby, who supplied him with additional information. Compiling the dictionary took Cregeen over 20 years of meticulous research, travelling throughout the island, visiting farms and cottages and collecting words, phrases, and proverbs from the people he met. [3]

When the dictionary was ready for publication, Harrison wrote an introduction and the manuscript was brought to Manx printer John Quiggin for it to be printed. On the title page of the original edition, the publication date is 1835, although the dictionary was not published until 3 years later in 1838. This was because the title page was distributed as an advertisement in 1835 to gauge interest, and never updated when the dictionary actually went to print. [3]

The dictionary was ordered in an unusual way for a language that undergoes initial mutation of words, in that it is strictly alphabetical, including entries for mutated forms:

Both the first edition of the Dictionary (1835) and the second (1910) comprise a strictly alphabetical list of word forms, which is particularly valuable for users not entirely familiar with the nature and range of variation in the initial letter of Manx words, due to initial consonant mutations, and to the addition of consonants (such as d- or n-) before certain forms of vowel-initial verbs. A consequence of this strictly alphabetical procedure, though, is that related forms of the same word, or word-family, are scattered throughout the dictionary. Thus, in a sense, Cregeen’s Dictionary as published is more like an index to a lexicon than a lexicon itself. [5]

It is worth noting that Cregeen was not the first person to attempt to write a dictionary for the Manx language. Reverend John Kelly had attempted to do so in his A Triglot Dictionary of the Celtic Language, as spoken in Man, Scotland, and Ireland together with the English, but much of this was destroyed in a fire during publishing. [6] Cregeen would not have been aware of this as although Kelly's dictionary was partially extant in manuscript form, it was not published until decades later in 1866. [2]

Although the Manx language was in a period of decline even in Cregeen's own lifetime, his contribution was not forgotten. The centenary of the publication of his dictionary was celebrated in Peel in 1938, with William Cubbon, the director of the Manx Museum, stating that "we students would be poor without his precious book". [7] A year later a commemorative plaque was erected over the door of the house that Cregeen himself built in Colby. [3]

In more recent years, with the continued revival of the language in the Isle of Man, Culture Vannin has celebrated Cregeen's work by selecting some of the lesser known words from his dictionary and posting them on social media. [8]

Manx, also known as Manx Gaelic or Manks, is a Goidelic language of the insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, itself a branch of the Indo-European language family. Manx is the historical language of the Manx people.

The Manx cat is a breed of domestic cat originating on the Isle of Man, with a naturally occurring mutation that shortens the tail. Many Manx have a small stub of a tail, but Manx cats are best known as being entirely tailless; this is the most distinguishing characteristic of the breed, along with elongated hind legs and a rounded head. Manx cats come in all coat colours and patterns, though all-white specimens are rare, and the coat range of the original stock was more limited. Long-haired variants are sometimes considered a separate breed, the Cymric.

The culture of the Isle of Man is influenced by its Celtic and, to a lesser extent, its Norse origins, though its close proximity to the United Kingdom, popularity as a UK tourist destination, and recent mass immigration by British migrant workers has meant that British influence has been dominant since the Revestment period. Recent revival campaigns have attempted to preserve the surviving vestiges of Manx culture after a long period of Anglicisation, and significant interest in the Manx language, history and musical tradition has been the result.

Ballabeg is a village on the Isle of Man. It is in the parish of Arbory in the sheading of Rushen, in the south of the island near Castletown. There are several small villages and hamlets with the name, although Ballabeg in Arbory is the most well-known and populous.

In Scottish, Northern English, and Manx folklore, the first-foot is the first person to enter the home of a household on New Year's Day and is seen as a bringer of good fortune for the coming year. Similar practices are also found in Greek, Vietnamese, and Georgian new year traditions.

Manx English, or Anglo-Manx, is the historic dialect of English spoken on the Isle of Man, though today in decline. It has many borrowings from Manx, a Goidelic language, and it differs widely from any other variety of English, including dialects from other areas in which Celtic languages are or were spoken, such as Welsh English and Hiberno-English.

Arthur William Moore, CVO, SHK, JP, MA was a Manx antiquarian, historian, linguist, folklorist, and former Speaker of the House of Keys in the Isle of Man. He published under the sobriquet A. W. Moore.

Fenodyree in the folklore of the Isle of Man, is a hairy supernatural creature, a sort of sprite or fairy, often carrying out chores to help humans, like the brownies of the larger areas of Scotland and England.

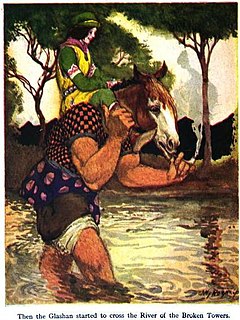

Glashtyn is a legendary creature from Manx folklore.

Philip Moore Callow Kermode, was a Manx antiquarian, historian and naturalist.

Surnames originating on the Isle of Man reflect the recorded history of the island, which can be divided into three different eras — Gaelic, Norse, and English. In consequence most Manx surnames are derived from the Gaelic or Norse languages.

John Joseph Kneen was a Manx linguist and scholar renowned for his seminal works on Manx grammar and on the place names and personal names of the Isle of Man. He is also a significant Manx dialect playwright and translator of Manx poetry. He is commonly best known for his translation of the Manx National Anthem into Manx.

Robert Archibald Armstrong, LL.D. (1788–1867), was a Gaelic lexicographer. He was the eldest son of Robert Armstrong, of Kenmore, Perthshire, by his wife, Mary McKercher. He was born at Kenmore in 1788, and educated partly by his father, and afterwards at Edinburgh and at St. Andrews University, here he graduated. Coming to London from St. Andrews with high commendations for his Greek and Latin acquirements, he engaged in tuition, and kept several high-class schools in succession in different parts of the metropolis. He devoted his leisure to the cultivation of literature and science. Of his humorous articles "The Three Florists," in Eraser for January 1838, and "The Dream of Tom Finiarty, the Cab-driver," in the Athenæum, are notable examples. His scientific papers appeared chiefly in the Arcana of Science and Art, and relate to meteorological matters. But his great work was A Gaelic Dictionary, in two parts — I. Gaelic and English, II. English and Gaelic — in which the words, in their different acceptations, are illustrated by quotations from the best Gaelic writers, London, 1825, 4to, This was the first Gaelic dictionary published, as there previously existed only vocabularies of the language like those of William Shaw and others.

John Kelly LL.D. was a Manx scholar, translator and clergyman.

The Bible was translated into the Manx language, a Gaelic language related to Irish and Scots Gaelic, in the 17th and 18th centuries.

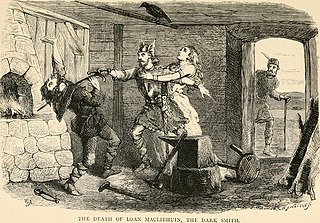

Loan Maclibuin was a legendary Norwegian smith. He was known as "The Dark Smith of Drontheim". He was the seventh son of Windy Cap, King of Norway. The "dark", does not refer to his working black magic, but rather to his swarthy nature.

William Cubbon M.A. was a Manx nationalist, antiquarian, author, businessman and librarian who was the first secretary of the Manx Museum, later becoming Director of the Museum.

Edmund Evans Greaves Goodwin was a Manx language scholar, linguist, and teacher. He is best known for his work First Lessons in Manx that he wrote to accompany the classes he taught in Peel.

Doug Fargher also known as Doolish y Karagher or Yn Breagagh, was a Manx language activist, author, and radio personality who was involved with the revival of the Manx language on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. He is best known for his English-Manx Dictionary (1979), the first modern dictionary for the Manx language. Fargher was involved in the promotion of Manx language, culture and nationalist politics throughout his life.

Max Wheeler is a British linguist noted for his work on the Catalan language. He is Emeritus Professor of Linguistics of the University of Sussex. His research into Catalan has primarily focused on phonology and on change in inflectional morphology.