Related Research Articles

Pope Pius VI was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1775 to his death in August 1799.

The Papal States, officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the Pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th century until the unification of Italy, which took place between 1859 and 1870, and culminated in their demise.

Pope Pius VII was head of the Catholic Church from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. He ruled the Papal States from June 1800 to 17 May 1809 and again from 1814 to his death. Chiaramonti was also a monk of the Order of Saint Benedict in addition to being a well-known theologian and bishop.

The Roman Republic was a sister republic of the First French Republic that existed from 1798 to 1799. It was proclaimed on 15 February 1798 after Louis-Alexandre Berthier, a general of the French Revolutionary Army, had occupied the city of Rome on 11 February. It was led by a Directory of five men and comprised territory conquered from the Papal States. The Roman Republic immediately incorporated two other former-papal revolutionary administrations, the Tiberina Republic and the Anconine Republic. It proved short-lived, as Neapolitan troops restored the Papal States in October 1799.

Don José Nicolás de Azara y Perera was a Spanish diplomat.

The papal conclave that followed the death of Pius VI on 29 August 1799 lasted from 30 November 1799 to 14 March 1800 and led to the selection of Cardinal Barnaba Chiaramonti, who took the name Pius VII. This conclave was held in Venice and was the last to take place outside Rome. This period was marked by uncertainty for the papacy and the Roman Catholic Church following the invasion of the Papal States and abduction of Pius VI under the French Directory.

The Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1801) were a series of conflicts fought principally in Northern Italy between the French Revolutionary Army and a Coalition of Austria, Russia, Piedmont-Sardinia, and a number of other Italian states.

Giovanni Battista Caprara Montecuccoli was an Italian statesman and cardinal and archbishop of Milan from 1802 to 1810. As a papal diplomat he served in the embassies in Cologne, Lausanne, and Vienna. As Legate of Pius VII in France, he implemented the Concordat of 1801, and negotiated with the Emperor Napoleon over the matter of appointments to the restored hierarchy in France. He crowned Napoleon as King of Italy in Milan in 1805.

Tolentino is a town and comune of about 19,000 inhabitants, in the province of Macerata in the Marche region of central Italy.

The Treaty of Tolentino was a peace treaty between Revolutionary France and the Papal States, signed on 19 February 1797 and imposing terms of surrender on the Papal side. The signatories for France were the French Directory's Ambassador to the Holy See, François Cacault, and the rising General Napoleon Bonaparte and opposite them four representatives of Pope Pius VI's curia.

The Napoleon Tiara was a papal tiara given to Pope Pius VII in June 1805 a few months after he presided at the coronation of Napoleon I. While lavishly decorated with jewels, it was deliberately too small and heavy to be worn and meant as an insult to the Pope. In the painting of The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David, the tiara is held behind the Pope by one of his aides.

Emilia is a historical region of northern Italy, which approximately corresponds to the western and the north-eastern portions of the modern region of Emilia-Romagna, with the area of Romagna forming the remainder of the modern region.

Vatican during the Savoyard era describes the relation of the Vatican to Italy, after 1870, which marked the end of the Papal States, and 1929, when the papacy regained autonomy in the Lateran Treaty, a period dominated by the Roman Question.

François Cacault was a French diplomat of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods.

The relationship between Napoleon and the Catholic Church was an important aspect of his rule.

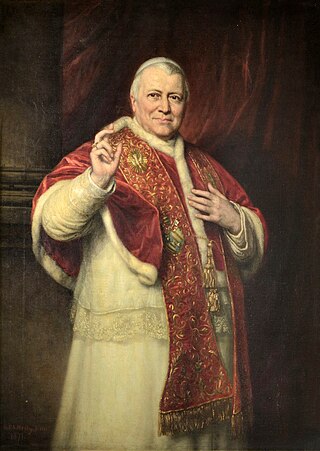

The Papal States under Pope Pius IX assumed a much more modern and secular character than had been seen under previous pontificates, and yet this progressive modernization was not nearly sufficient in resisting the tide of political liberalization and unification in Italy during the middle of the 19th century.

The modern history of the papacy is shaped by the two largest dispossessions of papal property in its history, stemming from the French Revolution and its spread to Europe, including Italy.

The Battle of Faenza, also known as the Battle of Castel Bolognese on February 3, 1797, saw a 7,000 troops from the Papal Army commanded by Michelangelo Alessandro Colli-Marchi facing 9,000 troops from the French Army under the command of Claude Victor-Perrin. The veteran French troops quickly overran the Papal army, inflicting disproportionate casualties. The town of Castel Bolognese was located on the banks of the Senio River 40 kilometres (25 mi) southeast of Bologna, and the city of Faenza was also nearby. The action took place during the War of the First Coalition, as part of the French Revolutionary Wars.

The papal nobility are the aristocracy of the Holy See, composed of persons holding titles bestowed by the Pope. From the Middle Ages into the nineteenth century, the papacy held direct temporal power in the Papal States, and many titles of papal nobility were derived from fiefs with territorial privileges attached. During this time, the Pope also bestowed ancient civic titles such as patrician. Today, the Pope still exercises authority to grant titles with territorial designations, although these are purely nominal and the privileges enjoyed by the holders pertain to styles of address and heraldry. Additionally, the Pope grants personal and familial titles that carry no territorial designation. Their titles being merely honorific, the modern papal nobility includes descendants of ancient Roman families as well as notable Catholics from many countries. All pontifical noble titles are within the personal gift of the pontiff, and are not recorded in the Official Acts of the Holy See.

The Diocese of Comacchio was a Roman Catholic diocese located in the coastal town of Comacchio in the province of Ferrara and region of Emilia Romagna, Italy. In 1986, the diocese of Commachio was united with the diocese of Ferrara to form the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Ferrara-Comacchio, and lost its individual identity.