Related Research Articles

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until the end of the war. He was commander during the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Arras, the Third Battle of Ypres, the German Spring Offensive, and the Hundred Days Offensive.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was the six divisions the British Army sent to the Western Front during the First World War. Planning for a British Expeditionary Force began with the 1906–1912 Haldane Reforms of the British Army carried out by the Secretary of State for War Richard Haldane following the Second Boer War (1899–1902).

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, was a senior British Army officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World War, in which he led the British Empire's Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign against the Ottoman Empire in the conquest of Palestine.

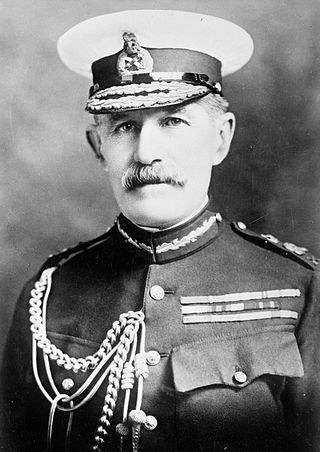

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres,, known as Sir John French from 1901 to 1916, and as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a senior British Army officer.

I Corps was an army corps in existence as an active formation in the British Army for most of the 80 years from its creation in the First World War until the end of the Cold War, longer than any other corps. It had a short-lived precursor during the Waterloo Campaign. It served as the operational component of the British Army of the Rhine during the Cold War, and was tasked with defending West Germany.

Field Marshal Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, 1st Baronet, was one of the most senior British Army staff officers of the First World War and was briefly an Irish unionist politician.

The Royal Regiment of Horse Guards (The Blues) (RHG) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, part of the Household Cavalry.

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien, was a British Army General. One of the few British survivors of the Battle of Isandlwana as a young officer, he also distinguished himself in the Second Boer War.

The II Corps was an army corps of the British Army formed in both the First World War and the Second World War. There had also been a short-lived II Corps during the Waterloo Campaign.

Field Marshal Sir Archibald Armar Montgomery-Massingberd,, known as Archibald Armar Montgomery until October 1926, was a senior British Army officer who served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) from 1933 to 1936. He served in the Second Boer War and in the First World War, and later was the driving force behind the formation of a permanent "Mobile Division", the fore-runner of the 1st Armoured Division.

Field Marshal Sir Henry Evelyn Wood, was a British Army officer. After an early career in the Royal Navy, Wood joined the British Army in 1855. He served in several major conflicts including the Indian Mutiny where, as a lieutenant, he was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for valour in the face of the enemy that is awarded to British and Imperial forces, for rescuing a local merchant from a band of robbers who had taken their captive into the jungle, where they intended to hang him. Wood further served as a commander in several other conflicts, notably the Third Anglo-Ashanti War, the Anglo-Zulu War, the First Boer War and the Mahdist War. His service in Egypt led to his appointment as Sirdar where he reorganised the Egyptian Army. He returned to Britain to serve as General Officer Commanding-in-Chief Aldershot Command from 1889, as Quartermaster-General to the Forces from 1893 and as Adjutant General from 1897. His last appointment was as commander of 2nd Army Corps from 1901 to 1904.

Lieutenant-General Sir James Moncrieff Grierson, ADC (Gen.) was a British soldier.

The Army Manoeuvres of 1913 was a large exercise held by the British Army in the Midlands in September 1913. Learning from the Army Manoeuvres of 1912, many more spotter aircraft were used. The Manoeuvres highlighted Sir John French's deficiencies as a commander.

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas D’Oyly Snow, was a British Army officer who fought on the Western Front during the First World War. He played an important role in the war, leading the 4th Division in the retreat of August 1914, and commanding VII Corps at the unsuccessful diversion of the Attack on the Gommecourt Salient on the first day on the Somme and at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917.

Lieutenant-General Sir Edwin Alfred Hervey Alderson, KCB was a senior British Army officer who served in several campaigns of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From 1915 to 1916 during the First World War he commanded the Canadian Expeditionary Force on the Western Front, during which time it saw heavy fighting.

The British Expeditionary Force order of battle 1914, as originally despatched to France in August and September 1914, at the beginning of World War I. The British Army prior to World War I traced its origins to the increasing demands of imperial expansion together with inefficiencies highlighted during the Crimean War, which led to the Cardwell and Childers Reforms of the late 19th century. These gave the British Army its modern shape, and defined its regimental system. The Haldane Reforms of 1907 formally created an Expeditionary force and the Territorial Force.

The Haldane Reforms were a series of far-ranging reforms of the British Army made from 1906 to 1912, and named after the Secretary of State for War, Richard Burdon Haldane. They were the first major reforms since the "Childers Reforms" of the early 1880s, and were made in the light of lessons newly learned in the Second Boer War.

Aldershot Command was a Home Command of the British Army.

The 1909 Birthday Honours for the British Empire were announced on 28 June, to celebrate the birthday of Edward VII.

Brigadier-General Philip Howell, was a senior British Army staff officer during the First World War. He was, successively, Brigadier General, General Staff (BGGS) to the Cavalry Corps and then to X Corps. In October 1915 he was posted as BGGS to the British Salonika Army before appointment as BGGS and second-in-command to II Corps, then forming part of the Fifth Army at the Battle of Somme in 1916.

References

- ↑ British Airships: Past, Present and Future: Chapter IV

- ↑ Boyle, Andrew (1962). "Chapter 5". Trenchard Man of Vision. St. James's Place London: Collins. pp. 103 to 104.

- 1 2 Warner, Philip Field-Marshal Earl Haig (London: Bodley Head, 1991; Cassell, 2001) pp107–109

- ↑ Reid 2006, p160

- ↑ Reid 2006, p159

- Macdiarmid, D.S. The Life of Sir James Moncrieff Grierson (London: Constable, 1923) pp244–248

- French, Edward Gerald [Sir John French's son] The Life of Field Marshal Sir John French, First Earl of Ypres (Cassell & Co, London, 1931) pp184–188 (covers French's opinions on the manoeuvres)

- Reid, Walter (2006). Architect of Victory: Douglas Haig. Birlinn Ltd, Edinburgh. ISBN 1-84158-517-3.