Related Research Articles

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War, he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until the end of the war. He was commander during the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Arras, the Third Battle of Ypres, the German Spring Offensive, and the Hundred Days Offensive.

The First Battle of the Marne was a battle of the First World War fought from 6 to 12 September 1914. It resulted in an Allied victory against the German armies in the west. The battle was the culmination of the Retreat from Mons and pursuit of the Franco–British armies which followed the Battle of the Frontiers in August and reached the eastern outskirts of Paris.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was the six-divisions the British Army sent to the Western Front during the First World War. Planning for a British Expeditionary Force began with the 1906–1912 Haldane reforms of the British Army carried out by the Secretary of State for War Richard Haldane following the Second Boer War (1899–1902).

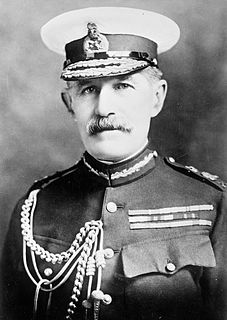

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres,, known as Sir John French from 1901 to 1916, and as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a senior British Army officer. Born in Kent to an Anglo-Irish family, he saw brief service as a midshipman in the Royal Navy, before becoming a cavalry officer. He achieved rapid promotion and distinguished himself on the Gordon Relief Expedition. French had a considerable reputation as a womaniser throughout his life, and his career nearly ended when he was cited in the divorce of a brother officer while in India in the early 1890s.

I Corps was an army corps in existence as an active formation in the British Army for most of the 80 years from its creation in the First World War until the end of the Cold War, longer than any other corps. It had a short-lived precursor during the Waterloo Campaign.

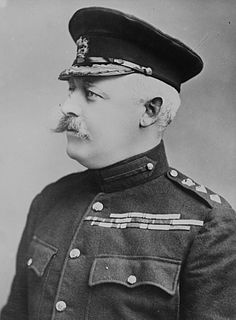

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien, was a British Army General. One of the few British survivors of the Battle of Isandlwana as a young officer, he also distinguished himself in the Second Boer War.

The Battle of Mons was the first major action of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in the First World War. It was a subsidiary action of the Battle of the Frontiers, in which the Allies clashed with Germany on the French borders. At Mons, the British Army attempted to hold the line of the Mons–Condé Canal against the advancing German 1st Army. Although the British fought well and inflicted disproportionate casualties on the numerically superior Germans, they were eventually forced to retreat due both to the greater strength of the Germans and the sudden retreat of the French Fifth Army, which exposed the British right flank. Though initially planned as a simple tactical withdrawal and executed in good order, the British retreat from Mons lasted for two weeks and took the BEF to the outskirts of Paris before it counter-attacked in concert with the French, at the Battle of the Marne.

The II Corps was an army corps of the British Army formed in both the First World War and the Second World War. There had also been a short-lived II Corps during the Waterloo Campaign.

General Sir Hubert de la Poer Gough was a senior officer in the British Army in the First World War. A favourite of the British Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, he experienced a meteoric rise through the ranks during the war and commanded the British Fifth Army from 1916 to 1918.

The Reserve Army was a field army of the British Army and part of the British Expeditionary Force during the First World War. On 1 April 1916, Lieutenant-General Sir Hubert Gough was moved from the command of I Corps and took over the Reserve Corps, which in June before the Battle of the Somme, was expanded and renamed Reserve Army. The army fought on the northern flank of the Fourth Army during the battle and became the Fifth Army on 30 October.

The Battle of the Frontiers was a series of battles fought along the eastern frontier of France and in southern Belgium, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War. The battles resolved the military strategies of the French Chief of Staff General Joseph Joffre with Plan XVII and an offensive interpretation of the German Aufmarsch II deployment plan by Helmuth von Moltke the Younger: the German concentration on the right (northern) flank, to wheel through Belgium and attack the French in the rear.

The Battle of Le Cateau was fought on the Western Front during the First World War on 26 August 1914. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French Fifth Army had retreated after their defeats at the Battle of Charleroi and the Battle of Mons. The British II Corps fought a delaying action at Le Cateau to slow the German pursuit. Most of the BEF was able to continue its retreat to Saint-Quentin.

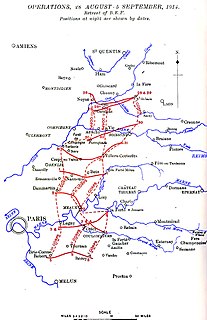

The Great Retreat, also known as the retreat from Mons, was the long withdrawal to the River Marne in August and September 1914 by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French Fifth Army. The Franco-British forces on the Western Front in the First World War had been defeated by the armies of the German Empire at the Battle of Charleroi and the Battle of Mons. A counter-offensive by the Fifth Army, with some assistance from the BEF, at the First Battle of Guise failed to end the German advance and the retreat continued over the Marne. From 5 to 12 September, the First Battle of the Marne ended the Allied retreat and forced the German armies to retire towards the Aisne River and to fight the First Battle of the Aisne (13–28 September). Reciprocal attempts to outflank the opposing armies to the north known as the Race to the Sea followed from (17 September to 17 October).

Michel-Joseph Maunoury was a commander of French forces in the early days of World War I who was posthumously elevated to the dignity of Marshal of France.

Lieutenant-General Sir James Moncrieff Grierson, ADC (Gen.) was a British soldier.

Charles Lanrezac was a French general, formerly a distinguished staff college lecturer, who commanded the French Fifth Army at the outbreak of the First World War.

The Army Manoeuvres of 1912 was the last military exercise of its kind conducted by the British Army before the outbreak of the First World War. In the manoeuvres, Sir James Grierson decisively beat Douglas Haig, calling into question Haig's abilities as a field commander.

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas D’Oyly Snow, was a British Army officer who fought on the Western Front during the First World War. He played an important role in the war, leading the 4th Division in the retreat of August 1914, and commanding VII Corps at the unsuccessful diversion of the Attack on the Gommecourt Salient on the first day on the Somme and at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917.

Aldershot Command was a Home Command of the British Army.

This article is about the role of Douglas Haig in 1918. In 1918, during the final year of the First World War, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig was Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front. Haig commanded the BEF in the defeat of the German Army's Spring Offensives, the Allied victory at Amiens in August, and the Hundred Days Offensive, which led to the war-ending armistice in November 1918.

References

- Report on the British Manoeuvres, 1913’ (unsigned) (cited in English translation in Patricia E. Prestwich, ‘French Attitudes Towards Britain, 1911–1914’ (Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, 1973) p297.)

- Reid, Walter (2006). Architect of Victory: Douglas Haig. Birlinn Ltd, Edinburgh. ISBN 1-84158-517-3.