Related Research Articles

A nursery rhyme is a traditional poem or song for children in Britain and many other countries, but usage of the term dates only from the late 18th/early 19th century. The term Mother Goose rhymes is interchangeable with nursery rhymes.

"Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" is a popular English lullaby. The lyrics are from an early-19th-century English poem written by Jane Taylor, "The Star". The poem, which is in couplet form, was first published in 1806 in Rhymes for the Nursery, a collection of poems by Taylor and her sister Ann. It is sung to the tune of the French melody "Ah! vous dirai-je, maman", which was published in 1761 and later arranged by several composers, including Mozart with Twelve Variations on "Ah vous dirai-je, Maman". The English lyrics have five stanzas, although only the first is widely known. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 7666.

Humpty Dumpty is a character in an English nursery rhyme, probably originally a riddle and one of the best known in the English-speaking world. He is typically portrayed as an anthropomorphic egg, though he is not explicitly described as such. The first recorded versions of the rhyme date from late eighteenth-century England and the tune from 1870 in James William Elliott's National Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs. Its origins are obscure, and several theories have been advanced to suggest original meanings.

"Old King Cole" is a British nursery rhyme first attested in 1708. Though there is much speculation about the identity of King Cole, it is unlikely that he can be identified reliably as any historical figure. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 1164. The poem describes a merry king who called for his pipe, bowl, and musicians, with the details varying among versions.

"Little Bo-Peep" or "Little Bo-Peep has lost her sheep" is a popular English language nursery rhyme. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 6487.

"Georgie Porgie" is a popular English language nursery rhyme. It has the Roud Folk Song Index number 19532.

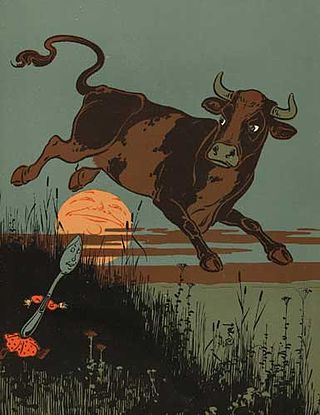

"Hey Diddle Diddle" is an English nursery rhyme. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 19478.

English folklore consists of the myths and legends of England, including the English region's mythical creatures, traditional recipes, urban legends, proverbs, superstitions, and folktales. Its cultural history is rooted in Celtic, Christian, and Germanic folklore.

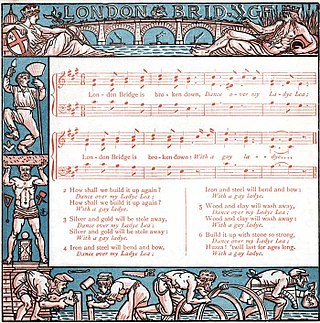

"London Bridge Is Falling Down" is a traditional English nursery rhyme and singing game, which is found in different versions all over the world. It deals with the dilapidation of London Bridge and attempts, realistic or fanciful, to repair it. It may date back to bridge-related rhymes and games of the Late Middle Ages, but the earliest records of the rhyme in English are from the 17th century. The lyrics were first printed in close to their modern form in the mid-18th century and became popular, particularly in Britain and the United States, during the 19th century.

"Little Jack Horner" is a popular English nursery rhyme with the Roud Folk Song Index number 13027. First mentioned in the 18th century, it was early associated with acts of opportunism, particularly in politics. Moralists also rewrote and expanded the poem so as to counter its celebration of greediness. The name of Jack Horner also came to be applied to a completely different and older poem on a folkloric theme; and in the 19th century it was claimed that the rhyme was originally composed in satirical reference to the dishonest actions of Thomas Horner in the Tudor period.

"Ring a Ring o' Roses", "Ring a Ring o' Rosie", or "Ring Around the Rosie", is a nursery rhyme, folk song and playground singing game. Descriptions first emerge in the mid-19th century, but are reported as dating from decades before, and similar rhymes are known from across Europe. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 7925.

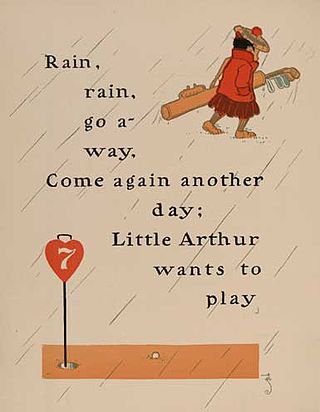

"Rain, Rain, Go Away" is a popular English language nursery rhyme. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 19096.

"Baa, Baa, Black Sheep" is an English nursery rhyme, the earliest printed version of which dates from around 1744. The words have not changed very much in two and a half centuries. It is sung to a variant of the 1761 French melody Ah! vous dirai-je, maman.

A children's song may be a nursery rhyme set to music, a song that children invent and share among themselves or a modern creation intended for entertainment, use in the home or education. Although children's songs have been recorded and studied in some cultures more than others, they appear to be universal in human society.

"As I was going by Charing Cross", is an English language nursery rhyme. The rhyme was first recorded in the 1840s, but it may have older origins in street cries and verse of the seventeenth century. It refers to the equestrian statue of King Charles I in Charing Cross, London, and may allude to his death or be a puritan satire on royalist reactions to his execution. It was not recorded in its modern form until the mid-nineteenth century. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 20564.

"Aiken Drum" is a popular Scottish folk song and nursery rhyme, which probably has its origins in a Jacobite song about the Battle of Sheriffmuir (1715).

"Rock-a-bye baby in the tree top" is a nursery rhyme and lullaby. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 2768.

"Taffy was a Welshman" is an English language nursery rhyme which was popular between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 19237.

"Oh, Dear! What Can the Matter Be?", also known as "Johnny's So Long at the Fair" is a traditional nursery rhyme that can be traced back as far as the 1770s in England. There are several variations on its lyrics. It has Roud Number 1279.

"The Queen of Hearts" is an English poem and nursery rhyme based on the characters found on playing cards, by an anonymous author, originally published with three lesser-known stanzas, "The King of Spades", "The King of Clubs", and "The Diamond King", in the British publication The European Magazine, vol. 1, no. 4, in April 1782. However, Iona and Peter Opie have argued that there is evidence to suggest that these other stanzas were later additions to an older poem.

References

- Green, Thomas (2009). Arthuriana: Early Arthurian Tradition and the Origins of the Legend (PDF). Louth, Lincs.: Lindes Press. ISBN 9781445221106 . Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter, eds. (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198600886 . Retrieved 20 November 2022.