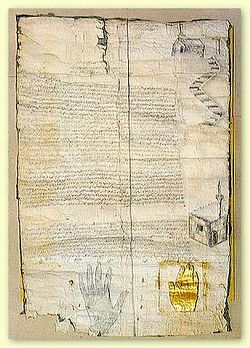

This is a letter which was issued by Mohammed, Ibn Abdullah, the Messenger, the Prophet, the Faithful, who is sent to all the people as a trust on the part of God to all His creatures, that they may have no plea against God hereafter—Verily God is the Mighty, the Wise. This letter is directed to the embracers of Islam, as a Covenant given to the followers of Nazerene in the East and West, the far and the near, the Arabs and foreigners, the known and the unknown.

This letter contains the oath given unto them, and he who disobeys that which is therein, will be considered a disobeyor and a transgressor to that whereunto he is commanded. He will be regarded as one who has corrupted the oath of God, disbelieved His Testament, rejected His Authority, despised His Religion, and made himself deserving of His Curse, whether he is a Sultan or any other believer of Islam.

Whenever monks, devotees and pilgrims gather together, whether in a mountain or valley, or den, or frequented place, or plain, or church, or in houses of worship, Verily we are back of them and shall protect them, and their properties and their morals, by Myself, by My friends and by My assistants, for they are of My subjects and under My protection.

I shall exempt them from that which may disturb them; of the burdens which are paid by others as an oath of allegiance. They must not give anything of their income but that which pleases them—they must not be offended, or disturbed, or coerced or compelled. Their judges should not be changed or prevented from accomplishing their offices, nor the monks disturbed in exercising their religious order, or the people of seclusion be stopped from dwelling in their cells.

No one is allowed to plunder their pilgrims, or destroy or spoil any of their churches, or houses of worship, or take any of the things contained within these houses and bring it to the houses of Islam. And he who takes away anything therefrom, will be one who has corrupted the oath of God, and, in truth, disobeyed His messenger.

Poll-taxes should not be put upon their judges, monks, and those whose occupation is the worship of God; nor is any other thing to be taken from them, whether it be a fine, a tax or any unjust right. Verily I shall keep their compact, wherever they may be, in the sea or on the land, in the East or West, in the North or South, for they are under My protection and the testament of My safety, against all things which they abhor.

No taxes or tithes should be received from those who devote themselves to the worship of God in the mountains, or from those who cultivate the Holy Lands. No one has the right to interfere with their affairs, or bring any action against them—Verily this is for aught else and not for them; rather, in the seasons of crops, they should be given a Kadah for each Ardab of wheat (about five bushels and a half) as provision for them, and no one has the right to say to them this is too much, or ask them to pay any tax.

As to those who possess properties, the wealthy and merchants, the poll-tax to be taken from them must not exceed twelve Dirhams a head per year. [a]

They shall not be imposed upon by any one to undertake a journey, or to be forced to go to wars or to carry arms; for the Islams have to fight for them. Do not dispute or argue with them, but deal according to the verse recorded in the Koran, to wit: 'Do not dispute or argue with the people of the Book but in that which is best.' Thus they will live favored and protected from everything which may offend them by the Callers to religion (Islam), wherever they may be and in any place they may dwell.

Should any Christian woman be married to a Musluman, such marriage must not take place except after her consent, and she must not be prevented from going to her church for prayer. Their churches must be honored and they must not be withheld from building churches or repairing convents.

They must not be forced to carry arms or stones; but the Islams must protect them and defend them against others. It is positively incumbent upon every one of the Islam nation not to contradict or disobey this oath until the Day of Resurrection and the end of the world. [6]