The Austroasiatic languagesOSS-troh-ay-zee-AT-ik, AWSS-, are a large language family in Mainland Southeast Asia, South Asia and East Asia. These languages are scattered throughout parts of Thailand, Laos, India, Myanmar, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Nepal, and southern China. Austroasiatic constitute the majority languages of Vietnam and Cambodia. There are around 117 million speakers of Austroasiatic languages, of which more than two-thirds are Vietnamese speakers. Of these languages, only Vietnamese, Khmer, and Mon have a long-established recorded history. Only two have official status as modern national languages: Vietnamese in Vietnam and Khmer in Cambodia. The Mon language is a recognized indigenous language in Myanmar and Thailand. In Myanmar, the Wa language is the de facto official language of Wa State. Santali is one of the 22 scheduled languages of India. The rest of the languages are spoken by minority groups and have no official status.

Demographic features of the population of Cambodia include population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

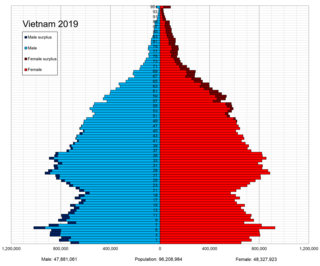

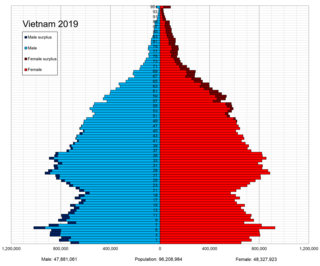

Demographic features of the population of Vietnam include population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

Majaz al Bab, also known as Medjez el Bab, or as Membressa under the Roman Empire, is a town in northern Tunisia. It is located at the intersection of roads GP5 and GP6, in the Plaine de la Medjerda.

The largest of the ethnic groups in Cambodia are the Khmer, who comprise approximately 90% of the total population and primarily inhabit the lowland Mekong subregion and the central plains. The Khmer historically have lived near the lower Mekong River in a contiguous arc that runs from the southern Khorat Plateau where modern-day Thailand, Laos and Cambodia meet in the northeast, stretching southwest through the lands surrounding Tonle Sap lake to the Cardamom Mountains, then continues back southeast to the mouth of the Mekong River in southeastern Vietnam.

The Bunong are an indigenous Cambodian ethnic minority group. They are found primarily in Mondulkiri province in Cambodia. The Bunong is the largest indigenous highland ethnic group in Cambodia. They have their own language called Bunong, which belongs to Bahnaric branch of Austroasiatic languages. The majority of Bunong people are animists, but a minority of them follows Christianity and Theravada Buddhism. After Cambodia's independence in 1953, Prince Sihanouk created a novel terminology, referring to the country's highland inhabitants, including the Bunong, as Khmer Loeu. Under the People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979-89), the generic term ជនជាតិភាគតិច "ethnic minorities" came to be in use and the Bunong became referred to as ជនជាតិព្នង meaning "ethnic Pnong". Today, the generic term that many Bunong use to refer to themselves is ជនជាតិដើមភាគតិច, which can be translated as "indigenous minority" and involves special rights, notably to collective land titles as an "indigenous community". In Vietnam, Bunong-speaking peoples are recurrently referred to as Mnong.

The Churu people are a Chams related ethnic group living mainly in Lâm Đồng, and Bình Thuận provinces of Central Vietnam. They speak Chru, a Malayo-Polynesian language. The word Churu means Land Expander in their language. The Churu's population was 23,242 in 2019.

Béni-oui-oui was a derogatory term for Muslims considered to be collaborators with the French colonial institutions in North Africa during the period of French rule. French administrators in Algeria relied heavily on Muslim intermediaries in their dealings with the indigenous population and many of these cadis, tax collectors or other tribal authorities were considered by nationalists to be mere rubber stamps and incapable of independent initiative.

Maleng, also known as Pakatan and Bo, is a Vietic language of Laos and Vietnam.

The k'ni, also known as mim or memm in Cambodia, popularly known as a mouth violin is a mouth resonator fiddle, i.e. a fiddle-like instrument used by the Jarai people in Vietnam and Tampuan people in Cambodia.

The Khmer Loeu is the collective name given to the various indigenous ethnic groups residing in the highlands of Cambodia. The Khmer Loeu are found mainly in the northeastern provinces of Ratanakiri, Stung Treng, and Mondulkiri. Most of the highland groups are Mon-Khmer peoples and are distantly related, to one degree or another, to the Khmer. Two of the Khmer Loeu groups are Chamic peoples, a branch of the Austronesian peoples, and have a very different linguistic and cultural background. The Mon–Khmer-speaking tribes are the aboriginal inhabitants of mainland Southeast Asia, their ancestors having trickled into the area from the northwest during the prehistoric metal ages. The Austronesian-speaking groups, Rade and Jarai, are descendants of the Malayo-Polynesian peoples who came to what is now coastal Vietnam; they established the Champa kingdoms, and after their decline migrated west over the Annamite Range, dispersing between the Mon–Khmer groups.

The Chaamba are an Arab tribe in the northern Sahara of central Algeria. They are a large tribe of Bedouins and live in a large desert territory to the south of the Atlas Mountains, around Metlili, El Golea, Ouargla, El Oued, and the Great Western Erg, including Timimoun and Béni Abbès While traditionally they were nomads specialised in raising camels and caravan trade, most have settled in the oases over the past century. The date palm is the most important agricultural product for the Chaamba.

The Katu people are an ethnic group of about 102,551 who live in eastern Laos and central Vietnam. Numbered among the Katuic peoples, they speak a Mon-Khmer language.

Michel Ferlus is a French linguist whose special study is in the historical phonology of languages of Southeast Asia. In addition to phonological systems, he also studies writing systems, in particular the evolution of Indic scripts in Southeast Asia.

Mrenh kongveal are beings in Cambodian folk mythology resembling elves of western folklore; they are particularly associated with guarding animals. By anecdotal accounts the roots of Mrenh kongveal appear to be uniquely Khmer. The mrenh kongveal are small in stature with bodies comparable in size to human children, and are fond of mischief. Offerings are often left to them when seeking their help.

The Sách is a Vietic ethnic group of Vietnam, native people of the mountains of Central Vietnamese province of Quảng Bình. The exonym Sách might have originated during the 15th century from the Sino-Vietnamese name for "register," which pre-modern Vietnamese texts used the term to designate villages that inhabited by various Austronesian and Austroasiatic highlanders. On the other hand, according to Michel Ferlus, the name's meaning may have relation with uncertain ancient Chinese terminologies. In Vietnam, they are considered a sub-ethnic group of the Chứt.

Sra peang is a rice wine stored in earthen pots and indigenous to several ethnic groups in Cambodia, in areas such as Mondulkiri or Ratanakiri. It is made of fermented glutinous rice mixed with several kinds of local herbs. The types and amount of herbs added differ according to ethnic group and region. This mixture is then put into a large earthenware jug, covered, and allowed to ferment for at least one month. The strength of this alcoholic beverage is typically 15 to 25 percent alcohol by volume.

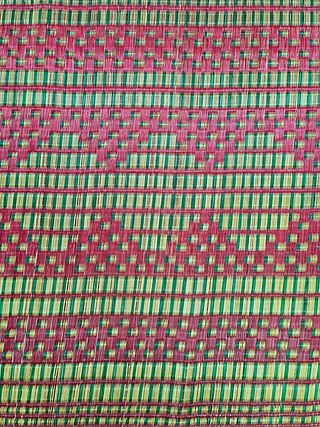

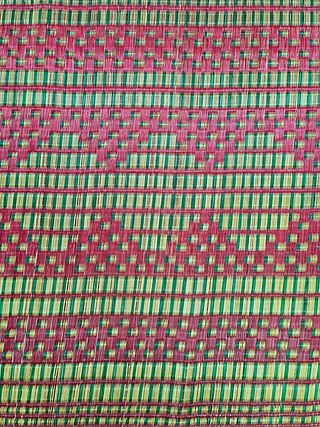

A Cambodian mat also known as a kantael is a woven mat made from palm or reed in Cambodia. The Cambodian mat consists of an ordinary mat, below which are fixed pads of strongly packed cotton, with the help of a special loom. They are specific to the Khmer people.

The Austroasiatic crossbow which is also known as the Hmong primitive bow, the Jarai crossbow, or the Angkorian crossbow is a crossbow used for war and for hunting in Southeast Asia. It has become a symbol of pride and identity for ethnic groups from Burma to the confines of Indochina.

A ballista elephant, also known as a Khmer ballista, is a war elephant mounted with a simple or double-bowed ballista which was used by the Angkorian civilization. They are considered as the summit of sophistication of Khmer weaponry comparable to the carrobalista in the legion of Vegetius.