A wildlife garden is an environment created with the purpose to serve as a sustainable haven for surrounding wildlife. Wildlife gardens contain a variety of habitats that cater to native and local plants, birds, amphibians, reptiles, insects, mammals and so on, and are meant to sustain locally native flora and fauna. Other names this type of gardening goes by can vary, prominent ones being habitat, ecology, and conservation gardening.

The Atlantic Forest is a South American forest that extends along the Atlantic coast of Brazil from Rio Grande do Norte state in the northeast to Rio Grande do Sul state in the south and inland as far as Paraguay and the Misiones Province of Argentina, where the region is known as Selva Misionera.

Threatened species are any species which are vulnerable to extinction in the near future. Species that are threatened are sometimes characterised by the population dynamics measure of critical depensation, a mathematical measure of biomass related to population growth rate. This quantitative metric is one method of evaluating the degree of endangerment.

A bird bath is an artificial puddle or small shallow pond, created with a water-filled basin, in which birds may drink, bathe, and cool themselves. A bird bath can be a garden ornament, small reflecting pool, outdoor sculpture, and also can be a part of creating a vital wildlife garden.

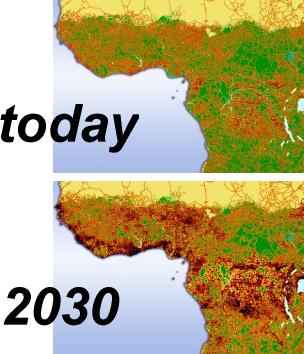

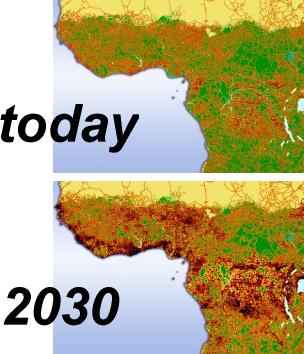

Habitat fragmentation describes the emergence of discontinuities (fragmentation) in an organism's preferred environment (habitat), causing population fragmentation and ecosystem decay. Causes of habitat fragmentation include geological processes that slowly alter the layout of the physical environment, and human activity such as land conversion, which can alter the environment much faster and causes the extinction of many species. More specifically, habitat fragmentation is a process by which large and contiguous habitats get divided into smaller, isolated patches of habitats.

The National Wildlife Federation (NWF) is the United States' largest private, nonprofit conservation education and advocacy organization, with over six million members and supporters, and 51 state and territorial affiliated organizations (including Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands).

Reconciliation ecology is the branch of ecology which studies ways to encourage biodiversity in the human-dominated ecosystems of the anthropocene era. Michael Rosenzweig first articulated the concept in his book Win-Win Ecology, based on the theory that there is not enough area for all of earth's biodiversity to be saved within designated nature preserves. Therefore, humans should increase biodiversity in human-dominated landscapes. By managing for biodiversity in ways that do not decrease human utility of the system, it is a "win-win" situation for both human use and native biodiversity. The science is based in the ecological foundation of human land-use trends and species-area relationships. It has many benefits beyond protection of biodiversity, and there are numerous examples of it around the globe. Aspects of reconciliation ecology can already be found in management legislation, but there are challenges in both public acceptance and ecological success of reconciliation attempts.

Battus philenor, the pipevine swallowtail or blue swallowtail, is a swallowtail butterfly found in North America and Central America. This butterfly is black with iridescent-blue hindwings. They are found in many different habitats, but are most commonly found in forests. Caterpillars are often black or red, and feed on compatible plants of the genus Aristolochia. They are known for sequestering acids from the plants they feed on in order to defend themselves from predators by being poisonous when consumed. The adults feed on the nectar of a variety of flowers. Some species of Aristolochia are toxic to the larvae, typically tropical varieties. While enthusiasts have led citizen efforts to conserve pipevine swallowtails in their neighborhoods on the West coast, the butterfly has not been the subject of a formal program in conservation or protected in legislation. The butterfly is however of "Special Concern" in Michigan, which is on the Northern limit of its range.

Natural landscaping, also called native gardening, is the use of native plants including trees, shrubs, groundcover, and grasses which are local to the geographic area of the garden.

The Tropical Andes is northern of the three climate-delineated parts of the Andes, the others being the Dry Andes and the Wet Andes. The Tropical Andes' area spans 1,542,644 km2 (595,618 sq mi).

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution during history. The term is equivalent to the concept of indigenous or autochthonous species. A wild organism is known as an introduced species within the regions where it was anthropogenically introduced. If an introduced species causes substantial ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage, it may be regarded more specifically as an invasive species.

Hymenocallis coronaria, commonly known as the Cahaba lily, shoal lily, or shoals spider-lily, is an aquatic, perennial flowering plant species of the genus Hymenocallis. It is endemic to the Southeastern United States, being found only in Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and parts of North Carolina. Within Alabama, it is known as the Cahaba lily; elsewhere it is known as the Shoal lily or Shoals spider-lily.

Satoyama is a Japanese term applied to the border zone or area between mountain foothills and arable flat land. Literally, sato means village, and yama means hill or mountain. Satoyama have been developed through centuries of small-scale agricultural and forestry use.

A wildlife corridor, habitat corridor, or green corridor is an area of habitat connecting wildlife populations separated by human activities or structures. This allows an exchange of individuals between populations, which may help prevent the negative effects of inbreeding and reduced genetic diversity that often occur within isolated populations. Corridors may also help facilitate the re-establishment of populations that have been reduced or eliminated due to random events. This may potentially moderate some of the worst effects of habitat fragmentation, wherein urbanization can split up habitat areas, causing animals to lose both their natural habitat and the ability to move between regions to access resources. Habitat fragmentation due to human development is an ever-increasing threat to biodiversity, and habitat corridors serve to manage its effects.

Conservation grazing or targeted grazing is the use of semi-feral or domesticated grazing livestock to maintain and increase the biodiversity of natural or semi-natural grasslands, heathlands, wood pasture, wetlands and many other habitats. Conservation grazing is generally less intensive than practices such as prescribed burning, but still needs to be managed to ensure that overgrazing does not occur. The practice has proven to be beneficial in moderation in restoring and maintaining grassland and heathland ecosystems. The optimal level of grazing will depend on the goal of conservation, and different levels of grazing, alongside other conservation practices, can be used to induce the desired results.

Urban wildlife is wildlife that can live or thrive in urban/suburban environments or around densely populated human settlements such as townships.

The biodiversity of Wales is the wide variety of ecosystems, living organisms, and the genetic makeups found in Wales.

Battus philenor hirsuta, the California pipevine swallowtail or hairy pipevine swallowtail, is a subspecies of the pipevine swallowtail that is endemic to Northern California in the United States. The butterfly is black with hindwings that have iridescent green-blue coloring above and a row of red spots below; the caterpillars are black with fleshy protrusions and orange spots. The subspecies' butterflies are smaller in size and hairier than the species, and they lay eggs in larger clutch sizes than the species. The egg clutches are deposited on the shoot tips of the California pipevine, a perennial vine native to riparian, chaparral, and woodland ecosystems of the California Coast Ranges, Sacramento Valley, and Sierra Nevada foothills. The larvae feed exclusively on the foliage and shoot tips of the pipevine, although adults eat floral nectar from a variety of plants. The plant contains a toxic substance, aristolochic acid. The larvae sequester the toxin, and both the juvenile and adult butterflies have high and toxic concentrations of the aristolochic acid in their tissues. Throughout the range of the species, Battus philenor, other butterflies and moths mimic the distinctive coloration of the swallowtail to avoid predators. However, there are no known mimics of the Californian subspecies.

The Peter Murrell Conservation Area is located in Huntingfield, Tasmania, approximately 15 km (9.3 mi) south of the state's capital city, Hobart. The conservation area has an area of 135 ha and is one of three reserves within the Peter Murrell Reserves. Also within these reserves are the Peter Murrell State Reserve and a Public Reserve. These reserves and the Conservation Area lie at the base of the Tinderbox Peninsula, between the suburbs of Kingston, Howden and Blackman's Bay. The Peter Murrell Conservation Area surrounds the northern, western and southern sides of the Peter Murrell State Reserve.

A pollinator garden is a type of garden designed with the intent of growing specific nectar and pollen-producing plants, in a way that attracts pollinating insects known as pollinators. Pollinators aid in the production of one out of every three bites of food consumed by humans, and pollinator gardens are a way to offer support for these species. In order for a garden to be considered a pollinator garden, it should provide various nectar producing flowers, shelter or shelter-providing plants for pollinators, and avoid the use of pesticides.