Related Research Articles

Bioleaching is the extraction of metals from their ores through the use of living organisms. This is much cleaner than the traditional heap leaching using cyanide. Bioleaching is one of several applications within biohydrometallurgy and several methods are used to recover copper, zinc, lead, arsenic, antimony, nickel, molybdenum, gold, silver, and cobalt.

Acid mine drainage, acid and metalliferous drainage (AMD), or acid rock drainage (ARD) is the outflow of acidic water from metal mines or coal mines.

Copper extraction refers to the methods used to obtain copper from its ores. The conversion of copper ores consists of a series of physical, chemical and electrochemical processes. Methods have evolved and vary with country depending on the ore source, local environmental regulations, and other factors.

Acidithiobacillus is a genus of the Acidithiobacillia in the phylum "Pseudomonadota". This genus includes ten species of acidophilic microorganisms capable of sulfur and/or iron oxidation: Acidithiobacillus albertensis, Acidithiobacillus caldus, Acidithiobacillus cuprithermicus, Acidithiobacillus ferrianus, Acidithiobacillus ferridurans, Acidithiobacillus ferriphilus, Acidithiobacillus ferrivorans, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, Acidithiobacillus sulfuriphilus, and Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans.A. ferooxidans is the most widely studied of the genus, but A. caldus and A. thiooxidans are also significant in research. Like all "Pseudomonadota", Acidithiobacillus spp. are Gram-negative and non-spore forming. They also play a significant role in the generation of acid mine drainage; a major global environmental challenge within the mining industry. Some species of Acidithiobacillus are utilized in bioleaching and biomining. A portion of the genes that support the survival of these bacteria in acidic environments are presumed to have been obtained by horizontal gene transfer.

Sulfur-reducing bacteria are microorganisms able to reduce elemental sulfur (S0) to hydrogen sulfide (H2S). These microbes use inorganic sulfur compounds as electron acceptors to sustain several activities such as respiration, conserving energy and growth, in absence of oxygen. The final product of these processes, sulfide, has a considerable influence on the chemistry of the environment and, in addition, is used as electron donor for a large variety of microbial metabolisms. Several types of bacteria and many non-methanogenic archaea can reduce sulfur. Microbial sulfur reduction was already shown in early studies, which highlighted the first proof of S0 reduction in a vibrioid bacterium from mud, with sulfur as electron acceptor and H

2 as electron donor. The first pure cultured species of sulfur-reducing bacteria, Desulfuromonas acetoxidans, was discovered in 1976 and described by Pfennig Norbert and Biebel Hanno as an anaerobic sulfur-reducing and acetate-oxidizing bacterium, not able to reduce sulfate. Only few taxa are true sulfur-reducing bacteria, using sulfur reduction as the only or main catabolic reaction. Normally, they couple this reaction with the oxidation of acetate, succinate or other organic compounds. In general, sulfate-reducing bacteria are able to use both sulfate and elemental sulfur as electron acceptors. Thanks to its abundancy and thermodynamic stability, sulfate is the most studied electron acceptor for anaerobic respiration that involves sulfur compounds. Elemental sulfur, however, is very abundant and important, especially in deep-sea hydrothermal vents, hot springs and other extreme environments, making its isolation more difficult. Some bacteria – such as Proteus, Campylobacter, Pseudomonas and Salmonella – have the ability to reduce sulfur, but can also use oxygen and other terminal electron acceptors.

Heap leaching is an industrial mining process used to extract precious metals, copper, uranium, and other compounds from ore using a series of chemical reactions that absorb specific minerals and re-separate them after their division from other earth materials. Similar to in situ mining, heap leach mining differs in that it places ore on a liner, then adds the chemicals via drip systems to the ore, whereas in situ mining lacks these liners and pulls pregnant solution up to obtain the minerals. Heap leaching is widely used in modern large-scale mining operations as it produces the desired concentrates at a lower cost compared to conventional processing methods such as flotation, agitation, and vat leaching.

Microbial corrosion, also called microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC), microbially induced corrosion (MIC) or biocorrosion, is "corrosion affected by the presence or activity (or both) of microorganisms in biofilms on the surface of the corroding material." This corroding material can be either a metal (such as steel or aluminum alloys) or a nonmetal (such as concrete or glass).

Lithotrophs are a diverse group of organisms using an inorganic substrate to obtain reducing equivalents for use in biosynthesis or energy conservation via aerobic or anaerobic respiration. While lithotrophs in the broader sense include photolithotrophs like plants, chemolithotrophs are exclusively microorganisms; no known macrofauna possesses the ability to use inorganic compounds as electron sources. Macrofauna and lithotrophs can form symbiotic relationships, in which case the lithotrophs are called "prokaryotic symbionts". An example of this is chemolithotrophic bacteria in giant tube worms or plastids, which are organelles within plant cells that may have evolved from photolithotrophic cyanobacteria-like organisms. Chemolithotrophs belong to the domains Bacteria and Archaea. The term "lithotroph" was created from the Greek terms 'lithos' (rock) and 'troph' (consumer), meaning "eaters of rock". Many but not all lithoautotrophs are extremophiles.

Ferroplasma is a genus of Archaea that belong to the family Ferroplasmaceae. Members of the Ferroplasma are typically acidophillic, pleomorphic, irregularly shaped cocci.

Microbial metabolism is the means by which a microbe obtains the energy and nutrients it needs to live and reproduce. Microbes use many different types of metabolic strategies and species can often be differentiated from each other based on metabolic characteristics. The specific metabolic properties of a microbe are the major factors in determining that microbe's ecological niche, and often allow for that microbe to be useful in industrial processes or responsible for biogeochemical cycles.

Biomining is the technique of extracting metals from ores and other solid materials typically using prokaryotes, fungi or plants. These organisms secrete different organic compounds that chelate metals from the environment and bring it back to the cell where they are typically used to coordinate electrons. It was discovered in the mid 1900s that microorganisms use metals in the cell. Some microbes can use stable metals such as iron, copper, zinc, and gold as well as unstable atoms such as uranium and thorium. Large chemostats of microbes can be grown to leach metals from their media. These vats of culture can then be transformed into many marketable metal compounds. Biomining is an environmentally friendly technique compared to typical mining. Mining releases many pollutants while the only chemicals released from biomining is any metabolites or gasses that the bacteria secrete. The same concept can be used for bioremediation models. Bacteria can be inoculated into environments contaminated with metals, oils, or other toxic compounds. The bacteria can clean the environment by absorbing these toxic compounds to create energy in the cell. Bacteria can mine for metals, clean oil spills, purify gold, and use radioactive elements for energy.

The outflow of acidic liquids and other pollutants from mines is often catalysed by acid-loving microorganisms; these are the acidophiles in acid mine drainage.

Cobalt extraction refers to the techniques used to extract cobalt from its ores and other compound ores. Several methods exist for the separation of cobalt from copper and nickel. They depend on the concentration of cobalt and the exact composition of the ore used.

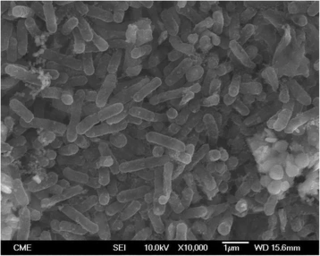

Acidithiobacillus caldus formerly belonged to the genus Thiobacillus prior to 2000, when it was reclassified along with a number of other bacterial species into one of three new genera that better categorize sulfur-oxidizing acidophiles. As a member of the Gammaproteobacteria class of Pseudomonadota, A. caldus may be identified as a Gram-negative bacterium that is frequently found in pairs. Considered to be one of the most common microbes involved in biomining, it is capable of oxidizing reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs) that form during the breakdown of sulfide minerals. The meaning of the prefix acidi- in the name Acidithiobacillus comes from the Latin word acidus, signifying that members of this genus love a sour, acidic environment. Thio is derived from the Greek word thios and describes the use of sulfur as an energy source, and bacillus describes the shape of these microorganisms, which are small rods. The species name, caldus, is derived from the Latin word for warm or hot, denoting this species' love of a warm environment.

Arsenate-reducing bacteria are bacteria which reduce arsenates. Arsenate-reducing bacteria are ubiquitous in arsenic-contaminated groundwater (aqueous environment). Arsenates are salts or esters of arsenic acid (H3AsO4), consisting of the ion AsO43−. They are moderate oxidizers that can be reduced to arsenites and to arsine. Arsenate can serve as a respiratory electron acceptor for oxidation of organic substrates and H2S or H2. Arsenates occur naturally in minerals such as adamite, alarsite, legrandite, and erythrite, and as hydrated or anhydrous arsenates. Arsenates are similar to phosphates since arsenic (As) and phosphorus (P) occur in group 15 (or VA) of the periodic table. Unlike phosphates, arsenates are not readily lost from minerals due to weathering. They are the predominant form of inorganic arsenic in aqueous aerobic environments. On the other hand, arsenite is more common in anaerobic environments, more mobile, and more toxic than arsenate. Arsenite is 25–60 times more toxic and more mobile than arsenate under most environmental conditions. Arsenate can lead to poisoning, since it can replace inorganic phosphate in the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate --> 1,3-biphosphoglycerate step of glycolysis, producing 1-arseno-3-phosphoglycerate instead. Although glycolysis continues, 1 ATP molecule is lost. Thus, arsenate is toxic due to its ability to uncouple glycolysis. Arsenate can also inhibit pyruvate conversion into acetyl-CoA, thereby blocking the TCA cycle, resulting in additional loss of ATP.

Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans, formerly known as Thiobacillus thiooxidans until its reclassification into the newly designated genus Acidithiobacillus of the Acidithiobacillia subclass of Pseudomonadota, is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that uses sulfur as its primary energy source. It is mesophilic, with a temperature optimum of 28 °C. This bacterium is commonly found in soil, sewer pipes, and cave biofilms called snottites. A. thiooxidans is used in the mining technique known as bioleaching, where metals are extracted from their ores through the action of microbes.

Pressure oxidation is a process for extracting gold from refractory ore.

Acidithrix ferrooxidans is a heterotrophic, acidophilic and Gram-positive bacterium from the genus Acidithrix. The type strain of this species, A. ferrooxidans Py-F3, was isolated from an acidic stream draining from a copper mine in Wales. This species grows in a variety of acidic environments such as streams, mines or geothermal sites. Mine lakes with a redoxcline support growth with ferrous iron as the electron donor. "A. ferrooxidans" grows rapidly in macroscopic streamer, producing greater cell densities than other streamer-forming microbes. Use in a bioreactors to remediate mine waste has been proposed due to cell densities and rapid oxidation of ferrous iron oxidation in acidic mine drainage. Exopolysaccharide production during metal substrate metabolism, such as iron oxidation helps to prevent cell encrustation by minerals.

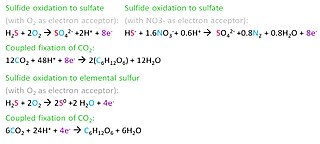

Microbial oxidation of sulfur is the oxidation of sulfur by microorganisms to build their structural components. The oxidation of inorganic compounds is the strategy primarily used by chemolithotrophic microorganisms to obtain energy to survive, grow and reproduce. Some inorganic forms of reduced sulfur, mainly sulfide (H2S/HS−) and elemental sulfur (S0), can be oxidized by chemolithotrophic sulfur-oxidizing prokaryotes, usually coupled to the reduction of oxygen (O2) or nitrate (NO3−). Anaerobic sulfur oxidizers include photolithoautotrophs that obtain their energy from sunlight, hydrogen from sulfide, and carbon from carbon dioxide (CO2).

References

- ↑ "Biooxidation – BioMineWiki". wiki.biomine.skelleftea.se. Retrieved 2017-03-16.