Background

There is some debate about the catalyst for the renewed Viking assault on the continent more generally and East Francia specifically at the end of the 9th century. According to the Chronicon of Regino of Prüm, the Vikings were forced to abandon their assault on Britain, which they had been attacking at least since the 8th century. Here the Vikings particularly focused their attention on Ireland, and once they established their presence there they began launching raids into neighboring England and across the channel into Europe. The Viking raids continued throughout much of Europe for much of the next couple of centuries. In 866, the Danish ‘Great Heathen Army’ began a major assault on England, whose fractured kingdoms were initially easy targets. They quickly took over East Anglia, Northumbria, and Mercia, but the king of the West Saxons, Alfred the Great, slowed their advance. In 878, at the Battle of Edington, Alfred defeated a prominent Danish leader, and the main force of Vikings moved from England to the continent where they continued raiding all over, even besieging the city of Paris in 885–886. Charlemagne's great-grandson, Charles the Fat, paid them a ransom of silver and sent them off to Burgundy where they continued raiding and plundering, even sacking the abbey of Luxeuil. [2]

Regino's Chronicon certainly reinforces this image, stating that after two decisive defeats in Britain, the Vikings moved their forces across the channel and began raiding and plundering the continent with renewed vigor. [3] Simon Coupland and Janet Nelson suggest that the defeat in England coupled with the unique conditions in Francia in the mid to late 9th century made that part of Europe a prime target for the Vikings. Louis the Stammerer died in April 879, leaving to his two young sons a kingdom that quickly erupted in turmoil. Frankish nobles supported differing contenders for the throne, and their internal divisions left them vulnerable to attacks across the channel from the migrating and opportunistic Danes, who took advantage of the situation. [4] Whatever the reasons, it is clear that the battle took place during a period of renewed and concentrated raiding by the Vikings on the European continent, centered on the fracturing Carolingian Empire.

The lead-up to the battle occurred during the summer of 891. While King Arnulf was off on the Bavarian frontier dealing with the Slavs, the Vikings met a Frankish force in battle on 26 June. The Franks were initially unsure about what their opponents’ aims were: would the Vikings make next for Cologne, head for Trier, or would they flee when they heard that a Frankish army had assembled to meet them in battle? The Franks eventually marched out and drew up in battle lines after crossing a stream called the Geule, then began discussing forming parties to scout their enemy. In the midst of these discussions the Vikings’ scouts happened upon the Franks. The Frankish army pursued the scouts without waiting for instruction from their leaders and eventually ran into the assembled Viking infantry in a nearby village, which easily repelled the disorganized Frankish attackers. Once their cavalry had been drawn to the battle, the Vikings easily defeated the Franks, who retreated, only to be cut down by their Viking pursuers. The Vikings then proceeded to raid and plunder, taking their captured booty back to their ships. [5]

Part of King Arnulf's motivation for going to battle against the Vikings, according to Regino, was to seek revenge for his fallen men and to restore the image of the Franks, which had been severely damaged by their flight during the battle. [6] Therefore, he assembled a substantial number of men and went to meet the Vikings in battle at the Dyle River, where the Danes were entrenched. [7]

Aftermath

After the battle a period of relative peace ensued in Francia, although the cause of this peace depends on the source. For example, some chroniclers, biased toward the Frankish side, state that it was the incredibly decisive defeat, where virtually all of the Danish forces were massacred, that stymied Viking raiding in the region for the next few years. Less biased chronicles, such as the Annals of St. Vaast, state that the real reason for the Viking departure was famine, which ravaged the countryside in 892. According to these Annals, the Vikings took to their ships to escape the famine and subsequently left the region in peace. [14]

These reports fail to represent the situation realistically, however. Viking raids continued in Francia and the rest of Europe for many decades. Merely a year, for instance, after the Battle of the Dyle, the Vikings again crossed the Meuse and raided the land of the Ripuarian Franks. [15] By 896, Viking raiders are again mentioned as active in the Loire and Oise valleys, and bands continued raiding in the Seine basin and northern Aquitaine into the early 10th century. [16] Rather than completely subduing the Viking raiders, the Battle of the Dyle merely ensured a period of short-lived peace in Francia.

Arnulf of Carinthia was the duke of Carinthia who overthrew his uncle Emperor Charles the Fat to become the Carolingian king of East Francia from 887, the disputed king of Italy from 894, and the disputed emperor from February 22, 896, until his death at Ratisbon, Bavaria.

Henry the Fowler was the Duke of Saxony from 912 and the King of East Francia from 919 until his death in 936. As the first non-Frankish king of East Francia, he established the Ottonian dynasty of kings and emperors, and he is generally considered to be the founder of the medieval German state, known until then as East Francia. An avid hunter, he obtained the epithet "the Fowler" because he was allegedly fixing his birding nets when messengers arrived to inform him that he was to be king.

Carloman was a Frankish king of the Carolingian dynasty. He was the eldest son of Louis the German, king of East Francia, and Hemma, daughter of a Bavarian count. His father appointed him governor of Carantania in 856, and commander of southeastern frontier marches in 864. Upon his father's death in 876 he became King of Bavaria. He was appointed by King Louis II of Italy as his successor, but the Kingdom of Italy was taken by his uncle Charles the Bald in 875. Carloman only conquered it in 877. In 879 he was incapacitated, perhaps by a stroke, and abdicated his domains in favour of his younger brothers: Bavaria to Louis the Younger and Italy to Charles the Fat.

Louis the Child, sometimes called Louis III or Louis IV, was the king of East Francia from 899 until his death and was also recognized as king of Lotharingia after 900. He was the last East Frankish ruler of the Carolingian dynasty. He succeeded his father, Arnulf, in East Francia and his elder illegitimate half-brother Zwentibold in Lotharingia.

Charles III, called the Simple or the Straightforward, was the king of West Francia from 898 until 922 and the king of Lotharingia from 911 until 923. He was a member of the Carolingian dynasty.

The Carolingian dynasty was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The dynasty consolidated its power in the 8th century, eventually making the offices of mayor of the palace and dux et princeps Francorum hereditary, and becoming the de facto rulers of the Franks as the real powers behind the Merovingian throne. In 751 the Merovingian dynasty which had ruled the Franks was overthrown with the consent of the Papacy and the aristocracy, and Pepin the Short, son of Martel, was crowned King of the Franks. The Carolingian dynasty reached its peak in 800 with the crowning of Charlemagne as the first Emperor of the Romans in the West in over three centuries. Nearly every monarch of France from Charlemagne's son Louis the Pious till the penultimate monarch of France Louis Philippe have been his descendants. His death in 814 began an extended period of fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and decline that would eventually lead to the evolution of the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire.

Louis III was King of West Francia from 879 until his death in 882. Despite questions of his legitimacy and challenges against his ascendance to the monarchy, Louis would prove to be an effective leader during his reign, notable for the defeat of Viking invaders at the Battle of Saucourt-en-Vimeu in August 881 that would later be immortalized in the poem Ludwigslied. He also led a less successful military campaign against Boso of Provence with help from Charles the Fat.

Charles III, also known as Charles the Fat, was the emperor of the Carolingian Empire from 881 to 887. A member of the Carolingian dynasty, Charles was the youngest son of Louis the German and Hemma, and a great-grandson of Charlemagne. He was the last Carolingian emperor of legitimate birth and the last to rule a united kingdom of the Franks.

Conrad I, called the Younger, was the king of East Francia from 911 to 918. He was the first king not of the Carolingian dynasty, the first to be elected by the nobility and the first to be anointed. He was chosen as the king by the rulers of the East Frankish stem duchies after the death of young King Louis the Child. Ethnically Frankish, prior to this election he had ruled the Duchy of Franconia from 906.

Zwentibold, a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was the illegitimate son of Emperor Arnulf. In 895, his father granted him the Kingdom of Lotharingia, which he ruled until his death.

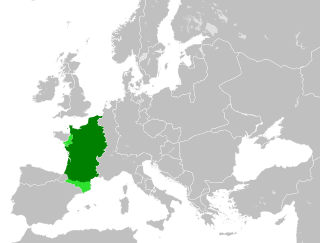

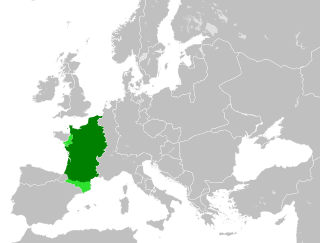

East Francia or the Kingdom of the East Franks was a successor state of Charlemagne's empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided the former empire into three kingdoms.

Rorik was a Danish Viking, who ruled over parts of Friesland between 841 and 873, conquering Dorestad and Utrecht in 850. Rorik swore allegiance to Louis the German in 873. He was born in Denmark around 800. He died at some point between 873 and 882.

In medieval historiography, West Francia or the Kingdom of the West Franks constitutes the initial stage of the Kingdom of France and extends from the year 843, from the Treaty of Verdun, to 987, the beginning of the Capetian dynasty. It was created from the division of the Carolingian Empire following the death of Louis the Pious, with its neighbor East Francia eventually evolving into the Kingdom of Germany.

Annales Bertiniani are late Carolingian, Frankish annals that were found in the Abbey of Saint Bertin, Saint-Omer, France, after which they are named. Their account is taken to cover the period 830-82, thus continuing the Royal Frankish Annals (741–829), from which, however, it has circulated independently in only one manuscript. They are available in the Monumenta Germaniæ Historica and in a later French edition taking into account a newly discovered manuscript . The Annals of St. Bertin are one of the principal sources of ninth-century Francia, and are particularly well-informed on events in the West Frankish sphere of Charles the Bald. The Annales Fuldenses are usually read as an East Frankish counterpart to their narrative.

Henry was the leading military commander of the last years of the Carolingian Empire. He was commander-in-chief under Kings Louis the Younger and Charles the Fat. His early career was mostly restricted to East Francia, his homeland, but after Charles inherited West Francia in 884 he was increasingly active there. During his time, raids by the Vikings peaked in Francia. The sources describe at least eight separate campaigns waged by Henry against the Vikings, most of them successful.

The March of Carinthia was a frontier district (march) of the Carolingian Empire created in 889. Before it was a march, it had been a principality or duchy ruled by native-born Slavic princes at first independently and then under Bavarian and subsequently Frankish suzerainty. The realm was divided into counties which, after the succession of the Carinthian duke to the East Frankish throne, were united in the hands of a single authority. When the march of Carinthia was raised into a Duchy in 976, a new Carinthian march was created. It became the later March of Styria.

Rodulf Haraldsson, sometimes Rudolf, from Old Norse Hróðulfr, was a Viking leader who raided the British Isles, West Francia, Frisia, and Lotharingia in the 860s and 870s. He was a son of Harald the Younger and thus a nephew of Rorik of Dorestad, and a relative of both Harald Klak and Godfrid Haraldsson, but he was "the black sheep of the family". He was baptised, but under what circumstances is unknown. His career is obscure, but similar accounts are found in the three major series of Reichsannalen from the period: the Annales Bertiniani from West Francia, the Annales Fuldenses from East Francia, and the Annales Xantenses from Middle Francia. He died in an unsuccessful attempt to impose a danegeld on the locals of the Ostergo.

Hemming Halfdansson was "of the Danish race, a most Christian leader". He was probably a son of Halfdan, a leading Dane who became a vassal of Charlemagne in 807. He was probably related to the Danish royal family, as "Hemming" was one of their favoured names. The onomastic evidence includes the Danish king Hemming I and then a Hemming II, who was recalled to Denmark from Francia by his brothers Harald Klak and Reginfrid after Hemming I's death. This Hemming was probably the same person as Hemming Halfdansson. He probably soon returned to Francia, since there is no evidence of him in Danish politics after he and his brothers were driven out by the sons of Godfrid in 813.

The term "Viking Age" refers to the period roughly from 790s to the late 11th century in Europe, though the Norse raided Scotland's western isles well into the 12th century. In this era, Viking activity started with raids on Christian lands in England and eventually expanded to mainland Europe, including parts of present-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.

Vikings were active in Brittany during the Middle Ages, even occupying a portion of it for a time. Throughout the 9th century, the Bretons faced threats from various flanks: they resisted full incorporation into the Frankish Carolingian Empire yet they also had to repel an emerging threat of the new duchy of Normandy on their eastern border by these Scandinavian colonists.