Related Research Articles

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of Lentivirus that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immune system allows life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers to thrive. Without treatment, average survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype.

Various fringe theories have arisen to speculate about purported alternative origins for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), with claims ranging from it being due to accidental exposure to supposedly purposeful acts. Several inquiries and investigations have been carried out as a result, and each of these theories has consequently been determined to be based on unfounded and/or false information. HIV has been shown to have evolved from or be closely related to the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) in West Central Africa sometime in the early 20th century. HIV was discovered in the 1980s by the French scientist Luc Montagnier. Before the 1980s, HIV was an unknown deadly disease.

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) is a species of retrovirus that cause persistent infections in at least 45 species of non-human primates. Based on analysis of strains found in four species of monkeys from Bioko Island, which was isolated from the mainland by rising sea levels about 11,000 years ago, it has been concluded that SIV has been present in monkeys and apes for at least 32,000 years, and probably much longer.

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) AIDS hypothesis is a now-discredited hypothesis that the AIDS pandemic originated from live polio vaccines prepared in chimpanzee tissue cultures, accidentally contaminated with simian immunodeficiency virus and then administered to up to one million Africans between 1957 and 1960 in experimental mass vaccination campaigns.

C-C chemokine receptor type 5, also known as CCR5 or CD195, is a protein on the surface of white blood cells that is involved in the immune system as it acts as a receptor for chemokines.

AIDS is caused by a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which originated in non-human primates in Central and West Africa. While various sub-groups of the virus acquired human infectivity at different times, the present pandemic had its origins in the emergence of one specific strain – HIV-1 subgroup M – in Léopoldville in the Belgian Congo in the 1920s.

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual may not notice any symptoms, or may experience a brief period of influenza-like illness. Typically, this is followed by a prolonged incubation period with no symptoms. If the infection progresses, it interferes more with the immune system, increasing the risk of developing common infections such as tuberculosis, as well as other opportunistic infections, and tumors which are rare in people who have normal immune function. These late symptoms of infection are referred to as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). This stage is often also associated with unintended weight loss.

HIV/AIDS was recognised as a novel illness in the early 1980s. An AIDS case is classified as "early" if the death occurred before 5 June 1981, when the AIDS epidemic was formally recognized by medical professionals in the United States.

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 6 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CXCR6 gene. CXCR6 has also recently been designated CD186.

Neutral alpha-glucosidase C is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the GANC gene.

The subtypes of HIV include two major types, HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV type 2 (HIV-2). HIV-1 is related to viruses found in chimpanzees and gorillas living in western Africa, while HIV-2 viruses are related to viruses found in the sooty mangabey, a vulnerable West African primate. HIV-1 viruses can be further divided into groups M, N, O and P. The HIV-1 group M viruses predominate and are responsible for the AIDS pandemic. Group M can be further subdivided into subtypes based on genetic sequence data. Some of the subtypes are known to be more virulent or are resistant to different medications. Likewise, HIV-2 viruses are thought to be less virulent and transmissible than HIV-1 M group viruses, although HIV-2 is also known to cause AIDS. One of the obstacles to treatment of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is its high genetic variability.

Moloundou is an arrondissement (district) in the Boumba-et-Ngoko Division of southeastern Cameroon's East Province. Mouloundou is close to Boumba Bek and Nki National Parks on the Dja River. It has a mayor and several decentralised administrative services. Moloundou sits on the Ngoko River, directly across from Congo-Brazzaville.

Françoise Barré-Sinoussi is a French virologist and Director of the Regulation of Retroviral Infections Division and Professor at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, France. Born in Paris, France, Barré-Sinoussi performed some of the fundamental work in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the cause of AIDS. In 2008, Barré-Sinoussi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, together with her former mentor, Luc Montagnier, for their discovery of HIV. She mandatorily retired from active research on August 31, 2015 and fully retired by some time in 2017.

Janice Ellen Clements is vice dean for faculty at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the Mary Wallace Stanton Professor of Faculty Affairs. She is a professor in the departments of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology, Neurology, and Pathology, and has a joint appointment in molecular biology and genetics. Her molecular biology and virology research examines lentiviruses and how they cause neurological diseases.

Alexander F. Voevodin M.D., Ph.D., D.Sc., FRCPath is Russian-born biomedical scientist and educator. He is considered one of the leading early pioneers of HIV/AIDS research.

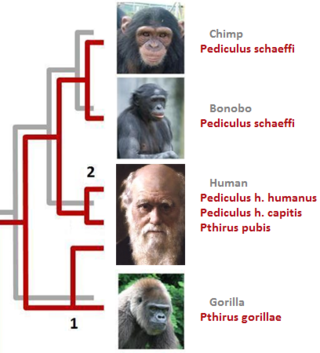

In parasitology and epidemiology, a host switch is an evolutionary change of the host specificity of a parasite or pathogen. For example, the human immunodeficiency virus used to infect and circulate in non-human primates in West-central Africa, but switched to humans in the early 20th century.

Anne Elizabeth Pusey is director of the Jane Goodall Institute Research Center and a professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University. Since the early 1990s, Pusey has been archiving the data collected from the Gombe chimpanzee project. The collection housed at Duke University consists of a computerized database that Pusey oversees. In addition to archiving Jane Goodall’s research from Gombe, she is involved in field study and advising students at Gombe. She was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 2022.

Bette Korber is an American computational biologist focusing on the molecular biology and population genetics of the HIV virus that causes infection and eventually AIDS. She has contributed heavily to efforts to obtain an effective HIV vaccine. She created a database at Los Alamos National Laboratory that has enabled her to design novel mosaic HIV vaccines, one of which is currently in human testing in Africa. The database contains thousands of HIV genome sequences and related data.

Theodora Hatziioannou is a Greek-American virologist. She known for her work discovering restriction factors that counteract HIV-AIDS and other primate lentiviruses, thus restricting them to specific species, and making it hard to study HIV-1 in animals. Her findings allowed her to develop the first HIV-1-based virus which is capable of recapitulating AIDS-like symptoms in a non-hominid. She is a Research Associate Professor in the Laboratory of Retrovirology at The Rockefeller University in New York. She is a co-author of a textbook on virology, Principles of Virology.

Janet K. Yamamoto is an American immunologist. Yanamoto is a professor of veterinary medicine at the University of Florida where she studies the spread of HIV/AIDS. In 1988, she co-developed a vaccine for the feline version of HIV with Niels C. Pederson and was subsequently elected to the National Academy of Inventors.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Beatrice Hahn, MD". Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology. Archived from the original on 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Viegas, Jennifer (2013-04-23). "Profile of Beatrice H. Hahn". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (17): 6613–6615. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.6613V. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305711110 . ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3637689 . PMID 23589843.

- 1 2 3 University of Alabama at Birmingham (May 26, 2006). "Researchers Confirm HIV-1 Originated In Wild Chimpanzees". Science Daily. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kreeger, Karen (April 21, 2016). "Beatrice H. Hahn, MD, Virologist from Penn's Perelman School of Medicine Elected to American Academy of Arts and Sciences". Penn Medicine. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Beatrice Hahn and George Shaw, Pioneers in HIV Research, to Join Penn Medicine". Penn Medicine. September 23, 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- 1 2 Svitil, Kathy (1 November 2002). "The 50 Most Important Women in Science". Discover. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Microbiology, Immunology, and Cancer Biology Seminar Series: Winford P. Larson Lectureship". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ↑ Viegas, Jennifer (2013-04-23). "Profile of Beatrice H. Hahn". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (17): 6613–6615. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.6613V. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305711110 . ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3637689 . PMID 23589843.

- ↑ "Research Teams". CHAVI-ID. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ↑ "Beatrice H. Hahn, MD, Virologist from Penn's Perelman School of Medicine Elected to American Academy of Arts and Sciences". Penn Medicine News. Penn Medicine. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- 1 2 "Beatrice H. Hahn, M.D." Perelman School of Medicine. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sharp, Paul; Hahn, Beatrice (27 August 2010). "The evolution of HIV-1 and the origin of AIDS". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365 (1552): 2487–2494. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0031. PMC 2935100 . PMID 20643738.

- 1 2 3 Sharp, Paul; Bailes, E; Chaudhuri, R; Rodenburg, CM; Santiago, MO; Hahn, BH (29 June 2001). "The origins of acquired immune deficiency syndrome viruses: where and when?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 356 (1410): 867–76. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.0863. PMC 1088480 . PMID 11405934.

- ↑ "Past Honorees BBJ's Top Birmingham Women, 1989-2000". Birmingham Business Journal. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ↑ "Dr. Beatrice H. Hahn". Who's Who in Health Care: Creel-Hall. Oct 13, 2002. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ↑ "Eighth Annual David Derse Memorial Lecture and Award". National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Research. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ Baillie, Katherine Unger (May 1, 2012). "Three Penn Faculty Elected to the National Academy of Sciences". Penn Today. Retrieved 19 October 2018.