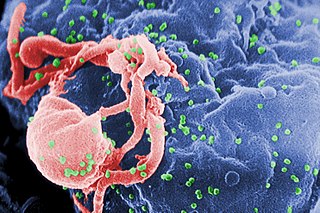

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of Lentivirus that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immune system allows life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers to thrive. Without treatment, the average survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype.

Bushmeat is meat from wildlife species that are hunted for human consumption. Bushmeat represents a primary source of animal protein and a cash-earning commodity in poor and rural communities of humid tropical forest regions of the world.

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) AIDS hypothesis is a now-discredited hypothesis that the AIDS pandemic originated from live polio vaccines prepared in chimpanzee tissue cultures, accidentally contaminated with simian immunodeficiency virus and then administered to up to one million Africans between 1957 and 1960 in experimental mass vaccination campaigns.

Chlorocebus is a genus of medium-sized primates from the family of Old World monkeys. Six species are currently recognized, although some people classify them all as a single species with numerous subspecies. Either way, they make up the entirety of the genus Chlorocebus.

The sooty mangabey is an Old World monkey found in forests from Senegal in a margin along the coast down to the Ivory Coast.

AIDS is caused by a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which originated in non-human primates in Central and West Africa. While various sub-groups of the virus acquired human infectivity at different times, the present pandemic had its origins in the emergence of one specific strain – HIV-1 subgroup M – in Léopoldville in the Belgian Congo in the 1920s.

The California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) is a federally funded biomedical research facility, dedicated to improving human and animal health, and located on the University of California, Davis, campus. The CNPRC is part of a network of seven National Primate Research Centers developed to breed, house, care for and study primates for medical and behavioral research. Opened in 1962, researchers at this secure facility have investigated many diseases, ranging from asthma and Alzheimer's disease to AIDS and other infectious diseases, and has also produced discoveries about autism. CNPRC currently houses about 4,700 monkeys, the majority of which are rhesus macaques, with a small population of South American titi monkeys. The center, located on 300 acres (1.2 km2) 2.5 miles west of the UC Davis campus, is sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Simian foamy virus (SFV) is a species of the genus Spumavirus that belongs to the family of Retroviridae. It has been identified in a wide variety of primates, including prosimians, New World and Old World monkeys, as well as apes, and each species has been shown to harbor a unique (species-specific) strain of SFV, including African green monkeys, baboons, macaques, and chimpanzees. As it is related to the more well-known retrovirus human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), its discovery in primates has led to some speculation that HIV may have been spread to the human species in Africa through contact with blood from apes, monkeys, and other primates, most likely through bushmeat-hunting practices.

HIV/AIDS was recognised as a novel illness in the early 1980s. An AIDS case is classified as "early" if the death occurred before 5 June 1981, when the AIDS epidemic was formally recognized by medical professionals in the United States.

HIV superinfection is a condition in which a person with an established human immunodeficiency virus infection acquires a second strain of HIV, often of a different subtype. These can form a recombinant strain that co-exists with the strain from the initial infection, as well from reinfection with a new virus strain, and may cause more rapid disease progression or carry multiple resistances to certain HIV medications.

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 6 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CXCR6 gene. CXCR6 has also recently been designated CD186.

The subtypes of HIV include two main subtypes, known as HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV type 2 (HIV-2). These subtypes have distinct genetic differences and are associated with different epidemiological patterns and clinical characteristics.

The agile mangabey is an Old World monkey of the white-eyelid mangabey group found in swampy forests of Central Africa in Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon, Gabon, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, and DR Congo. Until 1978, it was considered a subspecies of the Tana River mangabey. More recently, the golden-bellied mangabey has been considered a separate species instead of a subspecies of the agile mangabey.

The central chimpanzee or the tschego is a subspecies of chimpanzee. It can be found in Central Africa, mostly in Gabon, Cameroon, Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Nef is a small 27-35 kDa myristoylated protein encoded by primate lentiviruses. These include Human Immunodeficiency Viruses and Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV). Nef localizes primarily to the cytoplasm but also partially to the Plasma membrane (PM) and is one of many pathogen-expressed proteins, known as virulence factors, which function to manipulate the host's cellular machinery and thus allow infection, survival or replication of the pathogen. Nef stands for "Negative Factor" and although it is often considered indispensable for HIV-1 replication, in infected hosts the viral protein markedly elevates viral titers.

Janice Ellen Clements is vice dean for faculty at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the Mary Wallace Stanton Professor of Faculty Affairs. She is a professor in the departments of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology, Neurology, and Pathology, and has a joint appointment in molecular biology and genetics. Her molecular biology and virology research examines lentiviruses and how they cause neurological diseases.

Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (M-PMV), formerly Simian retrovirus (SRV), is a species of retroviruses that usually infect and cause a fatal immune deficiency in Asian macaques. The ssRNA virus appears sporadically in mammary carcinoma of captive macaques at breeding facilities which expected as the natural host, but the prevalence of this virus in feral macaques remains unknown. M-PMV was transmitted naturally by virus-containing body fluids, via biting, scratching, grooming, and fighting. Cross contaminated instruments or equipment (fomite) can also spread this virus among animals.

Beatrice H. Hahn is an American virologist and biomedical researcher best known for work which established that HIV, the virus causing AIDS, began as a virus passed from apes to humans. She is a professor of Medicine and Microbiology in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. In November 2002, Discover magazine listed Hahn as one of the 50 most important women scientists.

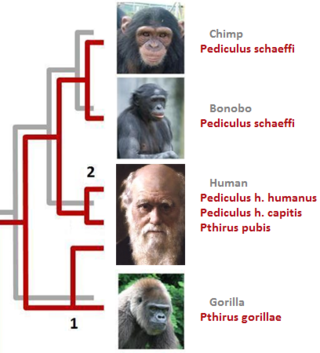

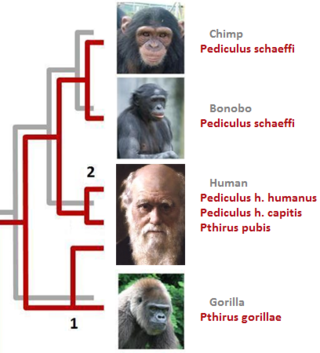

In parasitology and epidemiology, a host switch is an evolutionary change of the host specificity of a parasite or pathogen. For example, the human immunodeficiency virus used to infect and circulate in non-human primates in West-central Africa, but switched to humans in the early 20th century.

Theodora Hatziioannou is a Greek-American virologist. She known for her work discovering restriction factors that counteract HIV-AIDS and other primate lentiviruses, thus restricting them to specific species, and making it hard to study HIV-1 in animals. Her findings allowed her to develop the first HIV-1-based virus which is capable of recapitulating AIDS-like symptoms in a non-hominid. She is a Research Associate Professor in the Laboratory of Retrovirology at The Rockefeller University in New York. She is a co-author of a textbook on virology, Principles of Virology.