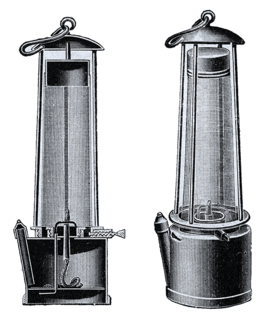

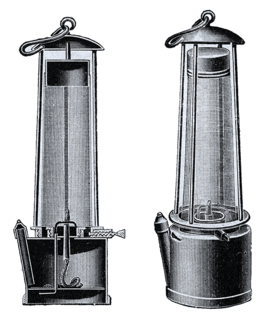

The Davy lamp is a safety lamp for use in flammable atmospheres, invented in 1815 by Sir Humphry Davy. It consists of a wick lamp with the flame enclosed inside a mesh screen. It was created for use in coal mines, to reduce the danger of explosions due to the presence of methane and other flammable gases, called firedamp or minedamp.

Firedamp is flammable gas found in coal mines. It is the name given to a number of flammable gases, especially coalbed methane. It is particularly found in areas where the coal is bituminous. The gas accumulates in pockets in the coal and adjacent strata, and when they are penetrated, the release can trigger explosions. Historically, if such a pocket was highly pressurized, it was termed a "bag of foulness".

The Blantyre mining disaster, which happened on the morning of 22 October 1877, in Blantyre, Scotland, was Scotland's worst ever mining accident. Pits No. 2 and No. 3 of William Dixon's Blantyre Colliery were the site of an explosion which killed 207 miners, the youngest being a boy of 11. It was known that firedamp was present in the pit and it is likely that this was ignited by a naked flame. The accident left 92 widows and 250 fatherless children.

Afterdamp is the toxic mixture of gases left in a mine following an explosion caused by firedamp, which itself can initiate a much larger explosion of coal dust. It consists of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and nitrogen. Hydrogen sulfide, another highly toxic gas, may also be present. However, it is the high content of carbon monoxide which kills by depriving victims of oxygen by combining preferentially with haemoglobin in the blood.

Trimdon Grange is a village in County Durham, in England. It is situated ten miles to the west of Hartlepool, and a short distance to the north of Trimdon.

Easington Colliery is a town in County Durham, England, known for a history of coal mining. It is situated to the north of Horden, and a short distance to the east of Easington Village. The town suffered a significant mining accident on 29 May 1951, when an explosion in the mine resulted in the deaths of 83 men.

A safety lamp is any of several types of lamp that provides illumination in coal mines and is designed to operate in air that may contain coal dust or gases, both of which are potentially flammable or explosive. Until the development of effective electric lamps in the early 1900s, miners used flame lamps to provide illumination. Open flame lamps could ignite flammable gases which collected in mines, causing explosions; safety lamps were developed to enclose the flame and prevent it from igniting the surrounding atmosphere. Flame safety lamps have been replaced in mining with sealed explosion-proof electric lights.

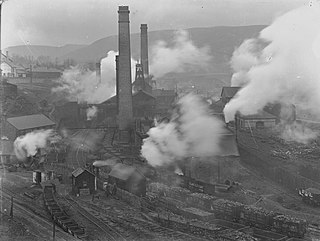

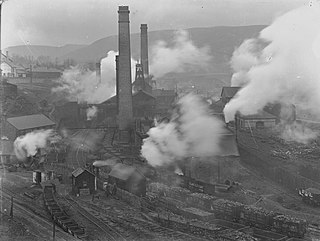

The Senghenydd colliery disaster, also known as the Senghenydd explosion, occurred at the Universal Colliery in Senghenydd, near Caerphilly, Glamorgan, Wales, on 14 October 1913. The explosion, which killed 439 miners and a rescuer, is the worst mining accident in the United Kingdom. Universal Colliery, on the South Wales Coalfield, extracted steam coal, which was much in demand. Some of the region's coal seams contained high quantities of firedamp, a highly explosive gas consisting of methane and hydrogen.

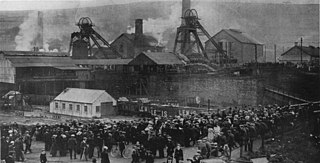

The Oaks Colliery explosion was a British mining disaster which occurred on 12 December 1866, killing 361 miners and rescuers at the Oaks Colliery at Hoyle Mill near Stairfoot in Barnsley, West Riding of Yorkshire. The disaster centred upon a series of explosions caused by firedamp, which ripped through the underground workings. It is the worst mining accident in England and the second worst mining disaster in the United Kingdom, after the Senghenydd colliery disaster in Wales.

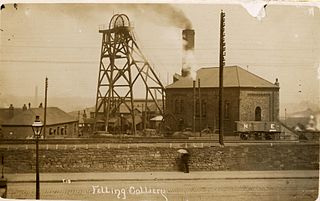

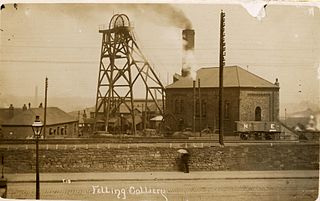

The Felling Colliery in Britain, suffered four disasters in the 19th century, in 1812, 1813, 1821 and 1847. By far the worst of the four was the 1812 disaster which claimed 92 lives on 25 May 1812. The loss of life in the 1812 disaster was one of the motivators for the development of the miners' safety lamp.

Mine rescue or mines rescue is the specialised job of rescuing miners and others who have become trapped or injured in underground mines because of mining accidents, roof falls or floods and disasters such as explosions caused by firedamp.

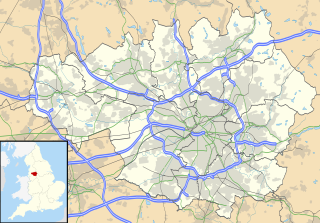

Clifton Hall Colliery was one of two coal mines in Clifton on the Manchester Coalfield, historically in Lancashire which was incorporated into the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England in 1974. Clifton Hall was notorious for an explosion in 1885 which killed around 178 men and boys.

The West Stanley colliery was a coal mine near Stanley. The mine opened in 1832 and was closed in 1936. Over the years several seams were worked through four shafts: Kettledrum pit, Lamp pit, Mary pit and New pit. In 1882 an underground explosion killed 13 men and in 1909 another explosion killed 168 men.

Bedford Colliery, also known as Wood End Pit, was a coal mine on the Manchester Coalfield in Bedford, Leigh, Lancashire, England. The colliery was owned by John Speakman, who started sinking two shafts on land at Wood End Farm in the northeast part of Bedford, south of the London and North Western Railway's Tyldesley Loopline in about 1874. Speakman's father owned Priestners, Bankfield, and Broadoak collieries in Westleigh. Bedford Colliery remained in the possession of the Speakman family until it was amalgamated with Manchester Collieries in 1929.

This is a partial glossary of coal mining terminology commonly used in the coalfields of the United Kingdom. Some words were in use throughout the coalfields, some are historic and some are local to the different British coalfields.

The Peckfield pit disaster was a mining accident at the Peckfield Colliery in Micklefield, West Yorkshire, England, which occurred on Thursday 30 April 1896, killing 63 men and boys out of 105 who were in the pit, plus 19 out of 23 pit ponies.

The Lundhill Colliery explosion was a coal mining accident which took place on 19 February 1857 in Wombwell, Yorkshire, UK in which 189 men and boys aged between 10 and 59 died. It is one of the biggest industrial disasters in the country's history and it was caused by a firedamp explosion. It was the first disaster to appear on the front page of the London Illustrated Times.

The Maypole Colliery disaster was a mining accident on 18 August 1908, when an underground explosion occurred at the Maypole Colliery, in Abram, near Wigan, then in the historic county of Lancashire, in North West England. The final death toll was 76.

The Cymmer Colliery explosion occurred in the early morning of 15 July 1856 at the Old Pit mine of the Cymmer Colliery near Porth, Wales, operated by George Insole & Son. The underground gas explosion resulted in a "sacrifice of human life to an extent unparalleled in the history of coal mining of this country" in which 114 men and boys were killed. Thirty-five widows, ninety-two children, and other dependent relatives were left with no immediate means of support.