The Marshall Plan was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion in economic recovery programs to Western European economies after the end of World War II. Replacing an earlier proposal for a Morgenthau Plan, it operated for four years beginning on April 3, 1948, though in 1951, the Marshall Plan was largely replaced by the Mutual Security Act. The goals of the United States were to rebuild war-torn regions, remove trade barriers, modernize industry, improve European prosperity and prevent the spread of communism. The Marshall Plan proposed the reduction of interstate barriers and the economic integration of the European Continent while also encouraging an increase in productivity as well as the adoption of modern business procedures.

Industrialisation (UK) or industrialization (US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for the purpose of manufacturing. Industrialisation is associated with increase of polluting industries heavily dependent on fossil fuels. With the increasing focus on sustainable development and green industrial policy practices, industrialisation increasingly includes technological leapfrogging, with direct investment in more advanced, cleaner technologies.

The Morgenthau Plan was a proposal to weaken Germany following World War II by eliminating its arms industry and removing or destroying other key industries basic to military strength. This included the removal or destruction of all industrial plants and equipment in the Ruhr. It was first proposed by United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. in a 1944 memorandum entitled Suggested Post-Surrender Program for Germany.

Camille Gutt, born Camille Guttenstein, was a Belgian economist, politician, and industrialist who served as the first managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from 1946 to 1951. He was the architect of a monetary reform plan that facilitated the recovery of the economy of Belgium after the Second World War.

The Wirtschaftswunder, also known as the Miracle on the Rhine, was the rapid reconstruction and development of the economies of West Germany and Austria after World War II. The expression referring to this phenomenon was first used by The Times in 1950.

The Japanese economic miracle refers to Japan's record period of economic growth between the post-World War II era and the beginning of the global Oil Crisis (1955-1973). During the economic boom, Japan rapidly became the world's third-largest economy, after the United States and the Soviet Union. By the 1970s, Japan was no longer expanding as quickly as it had in the previous decades despite per-worker productivity remaining high.

The Greek economic miracle describes a period of rapid and sustained economic growth in Greece from 1950 to 1973. At its height, the Greek economy grew by an average of 7.7 percent, second in the world only to Japan.

Alexandre Galopin was a Belgian businessman notable for his role in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. Galopin was director of the Société Générale de Belgique, a major Belgian company, and chairman of the board of the motor and armaments company Fabrique Nationale d'Armes de Guerre (FN). At the head of a group of Belgian industrialists and financiers, he gave his name to the "Galopin Doctrine" which prescribed how Belgian industry should deal with the moral and economic choices imposed by the occupation. In February 1944, he was assassinated by Flemish collaborators from the DeVlag group.

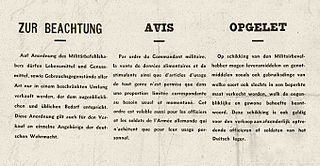

The Military Administration in Belgium and Northern France was an interim occupation authority established during the Second World War by Nazi Germany that included present-day Belgium and the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais. The administration was also responsible for governing the zone interdite, a narrow strip of territory running along the French northern and eastern borders. It remained in existence until July 1944. Plans to transfer Belgium from the military administration to a civilian administration were promoted by the SS, and Hitler had been ready to do so until Autumn 1942, when he put off the plans for what was intended to be temporary but ended up being permanent until the end of German occupation. The SS had suggested either Josef Terboven or Ernst Kaltenbrunner as the Reich Commissioner of the civilian administration.

This article covers the Economic history of Europe from about 1000 AD to the present. For the context, see History of Europe.

The post–World–War–II economic expansion, also known as the postwar economic boom or the Golden Age of Capitalism, was a broad period of worldwide economic expansion beginning with the aftermath of World War II and ending with the 1973–1975 recession. The United States, the Soviet Union and Western European and East Asian countries in particular experienced unusually high and sustained growth, together with full employment.

The royal question was a major political crisis in Belgium that lasted from 1945 to 1951, coming to a head between March and August 1950. The question at stake surrounded whether King Leopold III could return to the country and resume his constitutional role amid allegations that his actions during World War II had been contrary to the provisions of the Belgian Constitution. The crisis brought Belgium to the brink of a civil war. It was eventually resolved by the abdication of Leopold in favour of his son King Baudouin in 1951.

The Secret Army was an organisation within the Belgian Resistance, active during the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. With more than 54,000 members, it was by far the largest resistance group active in the country.

The Belgian National Movement was a major group in the resistance in German-occupied Belgium during World War II with politically centre-right leanings.

The National Royalist Movement was a group within the Belgian Resistance in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. It was active chiefly in Brussels and Flanders and was the most politically right-wing of the major Belgian resistance groups.

The involvement of the Belgian Congo in World War II began with the German invasion of Belgium in May 1940. Despite Belgium's surrender, the Congo remained in the conflict on the Allied side, administered by the Belgian government in exile.

The Committee of Secretaries-General was a committee of senior civil servants and technocrats in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. It was formed shortly before the occupation to oversee the continued functioning of the civil service and state bureaucracy independently of the German military occupation administration.

The German occupation of Belgium during World War II began on 28 May 1940, when the Belgian army surrendered to German forces, and lasted until Belgium's liberation by the Western Allies between September 1944 and February 1945. It was the second time in less than thirty years that Germany had occupied Belgium.

Deindustrialisation refers to the process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial activity and employment in a country or region, especially heavy industry or manufacturing industry. Deindustrialisation is common to all mature Western economies, as international trade, social changes, and urbanisation have changed the financial demographics after World War II. Phenomena such as the mechanisation of labour render industrial societies obsolete, and lead to the de-establishment of industrial communities.

Moroccans and people of Moroccan descent, who come from various ethnic groups, form a distinct community in Belgium and part of the wider Moroccan diaspora. They represent the largest non-European immigrant population in Belgium and are widely referred to as Belgo-Marocains in French and Belgische Marokkanen in Dutch.