Cycling

One cyclist said of him:

"I was disappointed when we were introduced. I'd expected to meet the Prince of Darkness. Instead I found myself opposite a quiet man in his 50s, lightly tanned, little Armani glasses on his nose and a cigar between his lips. So this was the magician of doping, the great puppet-master?"

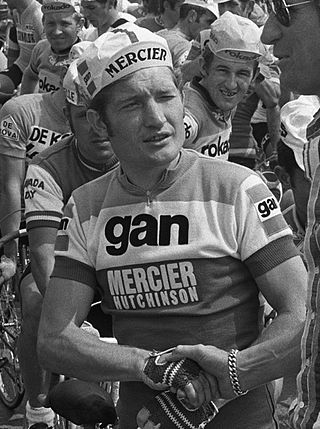

Bernard Sainz returned to cycling in 1972, joining the Mercier team when Louis Caput replaced Antonin Magne as manager. Caput approached Edmond Mercier, the bicycle-maker behind Poulidor's team, and asked to bring Sainz into the team management. Mercier agreed, said Sainz, because he was already treating Mercier for his own health problems. Mercier had also brought in the insurance company, GAN, as main sponsor. GAN, said Sainz, wanted Raymond Poulidor, who had said the previous year that he would not race any more. Sainz said:

Louis Caput couldn't stand the idea that such a monument of cycling could leave the sport by the back door. Poulidor agreed to meet me, although insisting that his decision to stop was irrevocable. In the style of a true Limousin, Poupou was reserved and careful, even defiant, but very quickly I sensed that he was attentive to what I was suggesting. I took his pulse for a long time as is the tradition in acupuncture, I examined the iris of his eyes according to the principles of iridology, and the soles of his feet according to the principles of reflexology. [18]

Sainz continued:

From the moment he started training again at home, in the Limousin, he rediscovered lost sensations... He called me three times a week. When he got to the traditional training camp on the Côte d'Azur, far from still believing as he had three months earlier that his career was over, he insisted on riding the races that opened the new season. I was obliged to intervene, to dissuade him, and then in face of his determination, to persuade him not to finish them. [19]

In Paris–Nice, the first important stage race of the season, Poulidor was 22 seconds behind Eddy Merckx on the morning of the last day. Poulidor attacked from the start, setting a speed record on the col de la Turbie that stood for more than 10 years and won Paris–Nice by two seconds. Next year he won Paris–Nice again and also the Dauphiné Libéré.

Sainz also treated Cyrille Guimard when pain in his knees was threatening his lead in the Tour de France. The two had met three years earlier. Sainz kept Guimard in the Tour even though the rider had sometimes to be carried from his bicycle. Sainz said:

It was at the time of our collaboration that the first accusations of doping came. An absurd rumour with a life as long as the Loch Ness monster because I saw it reappear in the Journal du Dimanche on 30 April 2000! For 30 years, people have been saying that I pushed Cyrille beyond his limits and that his knees ended up cracking in the 1972 Tour de France because of my methods. As is often the case, people talk and write, claiming to know everything when they know nothing. [20]

In 1986 he was cleared in an investigation into the trading of amphetamine at the Paris six-day race. He was questioned about illegal practice of medicine and held for two months in 1999. In 2002 police stopped him for speeding and driving without insurance [21] on the E17 autoroute in Belgium and found homeopathic medicines in his car. He told police he had been to see the Belgian cyclist, Frank Vandenbroucke. They went to see Vandenbroucke and found EPO, morphine and clenbuterol. Vandenbroucke claimed they were for his dog. [22]

The investigation brought out other names, such as Philippe Gaumont, who rode with Vandenbroucke at Cofidis and Yvon Ledanois of another team, Française des Jeux. Gaumont said Sainz gave them only homeopathic treatments. Vandenbroucke said he was naive but not dishonest in using Sainz, but that he was impressed at his results. [23]

On release from jail in Belgium, Sainz was re-arrested in France for breaking conditions imposed on him in 1999 to keep him away from the sport. [24] Ten used syringes were found in Sainz's office and he was accused of possessing and administering testosterone and corticoids. Sainz said the testosterone was to increase his sexual performance and the corticoids for treating horses. The case was dropped. [23]

Vandenbroucke, however, held a news conference in Ploegsteert, Belgium, to say he had always thought Sainz gave him homeopathic products but that he had doubts. He said Sainz had given him drops and injections. He said:

He (Sainz) said to me that they were completely legal homeopathic products. I wanted to trust him ... I was under the charm of Dr Mabuse. I may be considered naive but I am not a dishonest person. I want to believe that Mr Sainz only gave homeopathic care. I trusted him. Bernard Sainz proposed that he advise me. He seemed to be a strange man but was clearly a cycling expert. He impressed me greatly by showing me photographs of him administering his treatments to greats like Eddy Merckx, Lucien Van Impe, Bernard Hinault, Laurent Fignon, Cyril Guimard and many other great sportsmen like Alain Prost. [25] He explained to me that this care was based on natural methods and alternative medicines without endangering my health nor violating the ethics of our sport. [26]

He paid Sainz 7,000 French francs for the homeopathic drops and 50,000 in fees in the first half of 1999. Sainz said:

- I have concerned myself with him since autumn 1998. Not, as has been claimed, to get him doping products. Everybody knows perfectly, starting with the policemen who have listened to me for a long time, that riders don't need me for that sort of thing. To the contrary. If they turn to me, it's because they've heard of what I have been able to do [mes compétences diverses] for the great stars I have cited. [27]

The investigation that surrounded the Vandenbroucke inquiry linked Sainz to 51 athletes, of whom 33 were cyclists and others football players. [28]