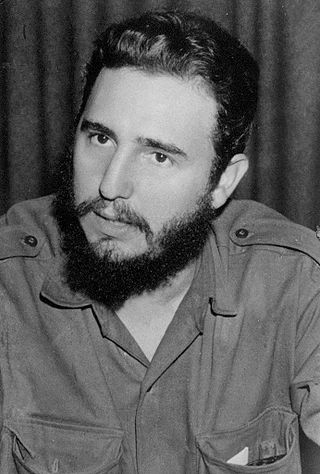

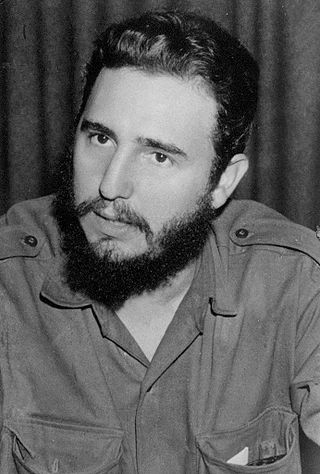

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 2008. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist and Cuban nationalist, he also served as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba from 1965 until 2011. Under his administration, Cuba became a one-party communist state; industry and business were nationalized, and socialist reforms were implemented throughout society.

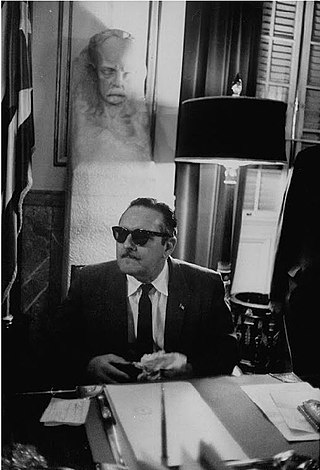

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar was a Cuban military officer and politician who played a dominant role in Cuban politics from his initial rise to power as part of the 1933 Revolt of the Sergeants until his overthrow in the Cuban Revolution in 1959. He served as elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944, and military dictator from 1952 to his 1959 resignation.

The Cuban Revolution was the military and political overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's dictatorship, which had reigned as the government of Cuba between 1952 and 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, which saw Batista topple the nascent Cuban democracy and consolidate power. Among those opposing the coup was Fidel Castro, then a novice attorney who attempted to contest the coup through Cuba's judiciary. Once these efforts proved fruitless, Fidel Castro and his brother Raúl led an armed attack on the Cuban military's Moncada Barracks on 26 July 1953.

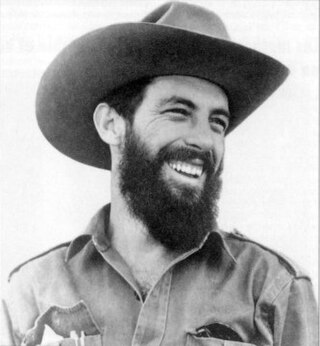

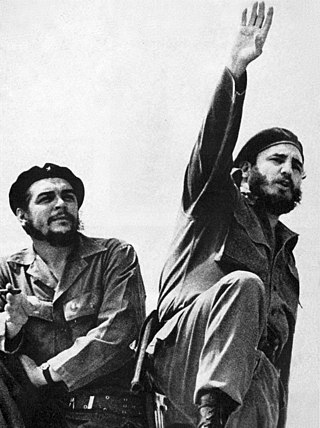

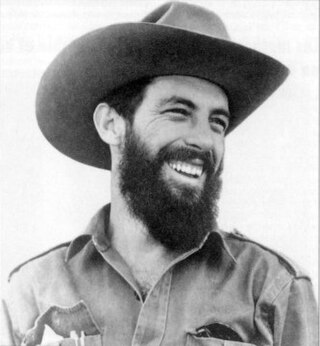

Camilo Cienfuegos Gorriarán was a Cuban revolutionary. One of the major figures of the Cuban Revolution, he was considered second only to Fidel Castro among the revolutionary leadership.

The 26 July Movement was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates the failed 1953 attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba, part of an attempt to overthrow the dictator Fulgencio Batista.

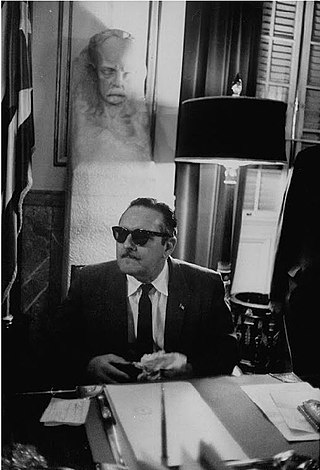

Manuel Urrutia Lleó was a liberal Cuban lawyer and politician. He campaigned against the Gerardo Machado government and the dictatorial second presidency of Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, before serving as president in the revolutionary government of 1959. Urrutia resigned his position after only seven months, owing to a series of disputes with revolutionary leader Fidel Castro, and emigrated to the United States shortly afterward.

Huber Matos Benítez was a Cuban military leader, political dissident, activist, and writer. He opposed the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista from its inception in 1952 and fought alongside Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro, Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos and other members of the 26th of July Movement to overthrow it. Following the success of the Cuban Revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power, he criticized the regime's shift in favor of Marxist principles and ties to the Popular Socialist Party (PSP). Convicted of treason and sedition by the revolutionary government, he spent 20 years in prison (1959–1979) before being released in 1979. He then divided his time between Miami, Florida, and Costa Rica while continuing to protest the policies of the Cuban government.

Frank País García was a Cuban revolutionary who campaigned for the overthrow of General Fulgencio Batista's government in Cuba. País was the urban coordinator of the 26th of July Movement, and was a key organizer within the urban underground movement, collaborating with Fidel Castro's guerrilla forces which were conducting activities in the Sierra Maestra mountains. País was killed in the streets of Santiago de Cuba by the Santiago police on July 30, 1957.

A guerrilla foco is a small cadre of revolutionaries operating in a nation's countryside. This guerrilla organization was popularized by Che Guevara in his book Guerrilla Warfare, which was based on his experiences in the Cuban Revolution. Guevara would go on to argue that a foco was politically necessary for the success of a socialist revolution. Originally Guevara theorized that a foco was only useful in overthrowing personalistic military dictatorships and not liberal democratic capitalism where a peaceful overthrow was believed possible. Years later Guevara would revise his thesis and argue all nations in Latin America, including liberal democracies, could be overthrown by a guerrilla foco. Eventually the foco thesis would be that political conditions would not even need to be ripe for revolutions to be successful, since the sheer existence of a guerrilla foco would create ripe conditions by itself. Guevara's theory of foco, known as foquismo, was self-described as the application of Marxism-Leninism to Latin American conditions, and would later be further popularized by author Régis Debray. The proposed necessity of a guerrilla foco proved influential in Latin America, but was also heavily criticized by other socialists.

The Cuban Revolution was the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's regime by the 26th of July Movement and the establishment of a new Cuban government led by Fidel Castro in 1959.

Mario Chanes de Armas was a former Cuban revolutionary and ally of Fidel Castro. He was a veteran of the attack on the Moncada barracks in July 1953 and served time in Batista's New Model Prison on the Isle of Pines with fellow revolutionary Fidel Castro. After Castro's rise to power, he was labeled an enemy of the regime and imprisoned for almost 30 years.

Ramón M. Barquín was a Cuban military colonel and opponent of former President Fulgencio Batista. Barquín was jailed by the Batista government for leading a failed coup attempt in 1956. He later fled Cuba in 1960 following the 1959 takeover by Fidel Castro.

The Triumph of the Revolution is the historical term for the flight of Fulgencio Batista on January 1, 1959, and the capture of Havana by the 26th of July Movement on January 8.

Humberto Sorí Marín was a Cuban revolutionary. After the Cuban Revolution in January 1959, he served as minister of agriculture, but resigned in May 1959. Shortly before the Bay of Pigs Invasion, he was arrested after landing in Cuba with arms and explosives, and was executed after the invasion.

Christopher Columbus, on his first Spanish-sponsored voyage to the Americas in 1492, sailed south from what is now the Bahamas to explore the northeast coast of Cuba and the northern coast of Hispaniola. Columbus, who was searching for a route to India, believed Cuba to be a peninsula of the Asian mainland. The first sighting of a Spanish ship approaching Cuba was on 28 October 1492, probably at Bariay, Holguín Province, on the eastern point of Cuba.

Fidelismo, otherwise known as Castroism, consists of the personal beliefs of Fidel Castro, which were often anti-imperialist, Cuban nationalist, supportive of Hispanidad, and later Marxist–Leninist. Castro described two historical figures as being particular influences on his political viewpoints: the Cuban anti-imperialist revolutionary José Martí, and the German sociologist and theorist Karl Marx. The thought of Che Guevara and Jules Régis Debray have also been important influences on Fidel Castro.

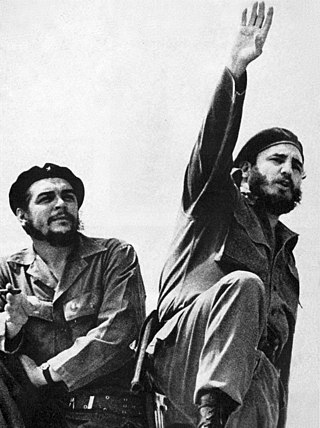

The Cuban communist revolutionary and politician Fidel Castro took part in the Cuban Revolution from 1953 to 1959. Following on from his early life, Castro decided to fight for the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's military junta by founding a paramilitary organization, "The Movement". In July 1953, they launched a failed attack on the Moncada Barracks, during which many militants were killed and Castro was arrested. Placed on trial, he defended his actions and provided his famous "History Will Absolve Me" speech, before being sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment in the Model Prison on the Isla de Pinos. Renaming his group the "26th of July Movement" (MR-26-7), Castro was pardoned by Batista's government in May 1955, claiming they no longer considered him a political threat while offering to give him a place in the government, but he refused. Restructuring the MR-26-7, he fled to Mexico with his brother Raúl Castro, where he met with Argentine Marxist-Leninist Che Guevara, and together they put a small revolutionary force intent on overthrowing Batista.

The consolidation of the Cuban Revolution is a period in Cuban history typically defined as starting in the aftermath of the revolution in 1959 and ending in 1962, after the total political consolidation of Fidel Castro as the maximum leader of Cuba. The period encompasses early domestic reforms, human rights violations, and the ousting of various political groups. This period of political consolidation climaxed with the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, which then cooled much of the international contestation that arose alongside Castro's bolstering of power.

The slogan "revolution first, elections later" was coined by Fidel Castro in a speech given on April 9, 1959. The speech famously announced the postponement of the elections promised by Fidel Castro, which were scheduled to occur after the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista. The announcement was the beginning of an electoral delay that culminated in the solidification of Fidel Castro's rule over Cuba. On May Day, 1960, Fidel Castro would outright condemn elections as corrupt, and cancel all future elections.

The institutionalization process, sometimes more formally referred to as the "process of institutionalization", or the "institutionalization of the Cuban Revolution", was a series of political reforms, typically identified by historians as to have taken place between 1976 and 1985, although sometimes identified as having begun in 1970. This process was proceeded by a period of government that was directly managed by Fidel Castro without much input from other officials, which had been status-quo since the conclusion of the Cuban Revolution. The institutionalization process was also proceeded by a deepening of Cuba-Soviet relations in the early 1970s, which had soured before in the 1960s.