Related Research Articles

The Lord's Prayer, also known by its incipit Our Father, is a central Christian prayer that Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew, and a shorter form in the Gospel of Luke when "one of his disciples said to him, 'Lord, teach us to pray, as John taught his disciples'". Regarding the presence of the two versions, some have suggested that both were original, the Matthean version spoken by Jesus early in his ministry in Galilee, and the Lucan version one year later, "very likely in Judea".

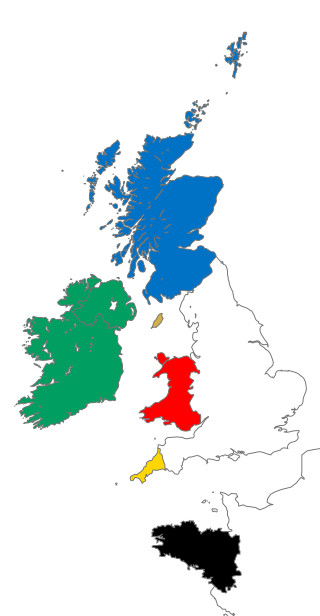

Manx, also known as Manx Gaelic, is a Gaelic language of the insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, itself a branch of the Indo-European language family. Manx is the historical language of the Manx people.

The culture of the Isle of Man is influenced by its Celtic and, to a lesser extent, its Norse origins, though its close proximity to the United Kingdom, popularity as a UK tourist destination, and recent mass immigration by British migrant workers has meant that British influence has been dominant since the Revestment period. Recent revival campaigns have attempted to preserve the surviving vestiges of Manx culture after a long period of Anglicisation, and significant interest in the Manx language, history and musical tradition has been the result.

Parts of the Bible have been translated into Welsh since at least the 15th century, but the most widely used translation of the Bible into Welsh for several centuries was the 1588 translation by William Morgan, Y Beibl cyssegr-lan sef Yr Hen Destament, a'r Newydd as revised in 1620. The Beibl Cymraeg Newydd was published in 1988 and revised in 2004. Beibl.net is a translation in colloquial Welsh which was completed in 2013.

Literature in the Manx language, which shares common roots with the Gaelic literature and Pre-Christian mythology of Ireland and Scotland, is known from at least the early 16th century, when the majority of the population still belonged to the Catholic Church in the Isle of Man.

Thomas Christian (1754–1828) was the translator of John Milton's Paradise Lost into Manx Gaelic, while leaving out passages in a way that were widely considered to have greatly improved the narrative structure of Milton's original. Rev. Christian was also an author of Manx carols and other Christian poetry important to Manx literature. He spent most of life as the Anglican vicar of Marown parish, Isle of Man.

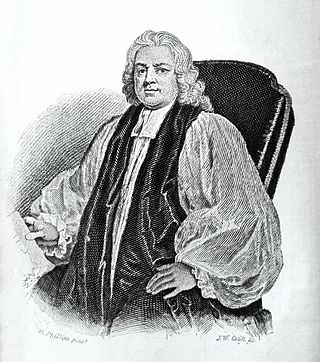

Thomas Wilson was Bishop of Sodor and Man between 1697 and 1755.

John Phillips was the Anglican Bishop of Sodor and Man between 1604 and 1633. He is best known for writing the first dateable text in the Manx language in his translation of the 1604 Book of Common Prayer in 1610.

Mark Hiddesley or Hildesley was an Anglican churchman. He served as vicar of Hitchin in Hertfordshire and later as Bishop of Sodor and Man between 1755 and 1772, where he encouraged Bible translations into Manx.

John Joseph Kneen was a Manx linguist and scholar renowned for his seminal works on Manx grammar and on the place names and personal names of the Isle of Man. He is also a significant Manx dialect playwright and translator of Manx poetry. He is commonly best known for his translation of the Manx National Anthem into Manx.

John Kelly LL.D. was a Manx scholar, translator and clergyman.

Translations of the Bible into Irish were first printed and published in the 17th century: the New Testament, the Tiomna Nuadh, in 1602, the Old Testament, the Sean Thiomna, in 1685, and the entire Bible, the Biobla in 1690.

Bible translations into Oceanic languages have a relatively closely related and recent history.

The Athabaskan language family is divided into the Northern Athabaskan, Pacific Coast Athabaskan and Southern Athabaskan groups. The full Bible has been translated into two Athabaskan languages, and the complete New Testament in five more. Another five have portions of the Bible translated into them. There are no Pacific Coast Athabaskan languages with portions of the Bible translated into them.

The New Testament was first published in Scottish Gaelic in 1767 and the whole Bible was first published in 1801. Prior to these, Gaels in Scotland had used translations into Irish.

Robert Corteen Carswell RBV is a Manx language and culture activist, writer and radio presenter. In 2013 he received the Manx Heritage Foundation's Reih Bleeaney Vanannan award for outstanding contributions to Manx culture.

Yn Çheshaght Ghailckagh, also known as the Manx Language Society and formerly known as Manx Gaelic Society, was founded in 1899 in the Isle of Man to promote the Manx language. The group's motto is Gyn çhengey, gyn çheer.

In addition to English, literature has been written in a wide variety of other languages in Britain, that is the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. This includes literature in Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, Latin, Cornish, Anglo-Norman, Guernésiais, Jèrriais, Manx, and Irish. Literature in Anglo-Saxon is treated as English literature and literature in Scots as Scottish literature.

Doug Fargher (1926–1987) also known as Doolish y Karagher or Yn Breagagh, was a Manx language activist, author, and radio personality who was involved with the revival of the Manx language on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. He is best known for his English-Manx Dictionary (1979), the first modern dictionary for the Manx language. Fargher was involved in the promotion of Manx language, culture and nationalist politics throughout his life.

Leslie Quirk, also known as Y Kione Jiarg, was a Manx language activist and teacher who was involved with the language's revival on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. His work recording the last native speakers of the language with the Irish Folklore Commission and the Manx Museum helped to ensure that a spoken record of the Manx language survived.

References

- ↑ Wheeler, Max (2019). "Phillips' Manx translation of the Psalms MNH MS 00003). Diplomatic edition". Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ Language death in the Isle of Man George Broderick, Carl Johan Sverdrup Marstrander, George Broderick - 1999 "However, it is due to his successor Bishop Mark Hildesley (1755-1772), also an Englishman, that we owe the main drive to having the full Bible translated into Manx and published 1763-73."

- ↑ Spelling and Society: The Culture and Politics of Orthography Page 65 Mark Sebba - 2007 ".. after the appearance of the Bible in Manx, it was possible for 'masters of families, and others, who are well disposed, [to] read to the ignorant and illiterate the Sacred Oracles in their own language' (Butler 1799: 227)."

- ↑ . Dictionary of National Biography . London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ↑ Weeden Butler, Life of Bishop Hildesley pp. 252–6)